Regional Connector: A Mixed Bag For Little Tokyoites

This story is part of a new series about the various urban planning developments taking place in parts of downtown Los Angeles called "What Will L.A. Look Like In 20 Years?" Click here for to see more from this series.

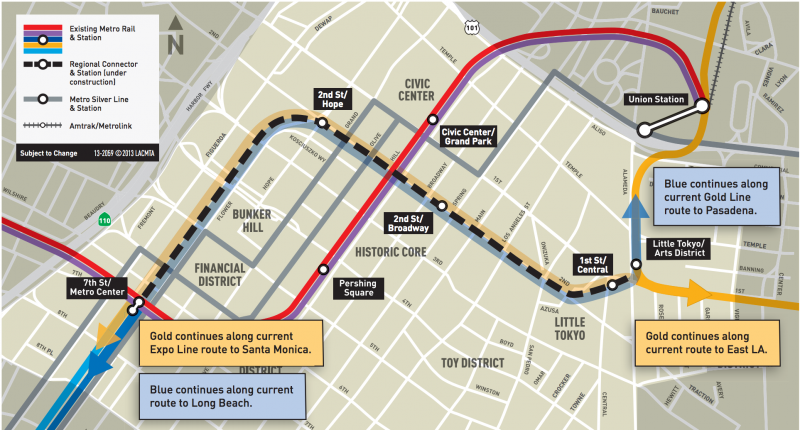

Little Tokyo will soon become one of the busiest transportation hubs in Los Angeles. A few weeks ago, Metro began construction on the Regional Connector, a 1.9-mile, three-station line in downtown that will connect the Gold Line to the rest of Metro’s light rail system. And while in theory, it’ll help move up to 90,000 people a day, decrease traffic congestion and increase economic opportunities across the area, not everyone is entirely thrilled.

When the line opens in 2020, the new station at 1st and Central is projected to become the busiest Metro station, after Union Station to the north. And while businesses are generally happy that there will be more visitors passing through the area, community organizers like Kristin Fukushima and Evelyn Yoshimura say it won’t matter if they’re not going to the right places.

“What does it mean to have new people coming in? Are they going to the fancy new restaurants that come in or are they going to the older stores that have been here forever?” asked Kristin Fukushima, a project manager with the Little Tokyo Community Council.

The neighborhood primarily comprises family businesses that have existed for decades, such as the famous ramen restaurant Daikokuya, Fugetsu-Do confectionery and Suehiro café. These shops are core parts of the Little Tokyo identity, said Evelyn Yoshimura, director of community organizing with the Little Tokyo Service Center. “Without those small family-owned businesses, Little Tokyo is no longer Little Tokyo.”

READ MORE: Garcetti Announces $670 Million Grant For Metro

Looming Gentrification

So far though, the new developments have helped bring in a new wave of visitors and tourists. Yoshimura said there definitely has been a surge in visitors within the past decade. Even on a quiet Monday night, you'll see people strolling through Japanese Village plaza, looking for a restaurant to eat at or a pastry shop to get dessert.

But with the latest wave of downtown development, Yoshimura worries that a new commercial center may draw visitors away from Little Tokyo.

“When does the flavor of the month change and we don’t become the hip, Yelped place to come? If it shifts somewhere else, what are we left with?” she asked, describing it as trying to embrace the best of gentrification while avoiding the worst.

Housing prices may pose a threat to its current residents as well. While the nightlife is dominated by young people, most of Little Tokyo’s residency is made up of 2,000 low-income seniors who don’t speak English. And there’s a fear that they, along with family businesses, might be pushed out.

In response, the Little Tokyo Community Council formed Sustainable Little Tokyo in 2012, a project aimed at developing the neighborhood in a way that “respects and enhances the neighborhood's history and culture.”

“We’re trying to get out ahead of development projects before vultures swoop in and developing these crazy high-rises that have nothing to do with the community because suddenly the land here is really valuable. It’s overall just scary,” said Fukushima.

SEE ALSO: Hollywood's Best Kept Secret: The Metro Red Line

Construction Woes

Street and sidewalk closures have already made it a bit trickier to navigate the area if you don’t frequent the area. So Fukushima says the focus is now on creating a marketing campaign with Metro to “convince people that Little Tokyo is still a place to come to, even if it’s a bit more difficult to come to.”

The original plans for the Connector included an option to run the line at street level. But after many months of pressure from the community, Metro pursued a below-ground route to avoid clogging streets.

In the long run, an underground line greatly increases train efficiency and decreases the chances of a train-vehicle collision; however, this also makes the project much more expensive. So the 1.9 miles of rail and three stations that the new connector will take comes in at a price tag of $1.427 billion, paid for by state and federal funds, as well as Measure R.

Not only is tunneling expensive, but it requires a staging area where a tunneling machine can be assembled and deployed. Since Little Tokyo is in the middle of a developed city, there isn’t any open land Metro could use - so it had to take the land from someone.

The north side of the block at 1st and Central streets just happened to be the perfect place for Metro. And Señor Fish, Spice Table and Weiland Brewery were now in the way.

Property owner Robert Volk, whose family has owned the land for over a century, was reluctant to relinquish the land, forcing Metro to then take it through eminent domain.

Dolores Roybal, a project manager overseeing the Regional Connector, lamented the acquisition. “It’s not something that we do lightly," she said. "It’s something that’s our last resort.”

But Metro justified the takeover, saying in its Environmental Impact Statement, “it is anticipated that, where relocation would be required, most of the jobs would be retained with the relocation. Therefore, there would be no net loss of jobs overall."

READ MORE: Don't Expect Anything Soon With L.A.'s New Skyscraper Regulations

Community Organization

Little Tokyo’s relationship with Metro has never been the best.

Fukushima also expressed frustration when Metro came around in 2009 with its early plans for the Regional Connector, just six years on from its opening of the Gold Line in 2003. Now, the community had yet another construction project to prepare for.

“The early relationship with them was really hostile and very tense. We didn’t feel like they were listening to us. They were doing community outreach in a checklist way,” Fukushima said. “They weren’t actually listening to us or taking our input into consideration.”

And according to Yoshimura, the community was originally going to vote against the Regional Connector because “they were not properly answering what the impact on businesses would be.” Because of this, it was simply too risky for them to allow a rail line they had no understanding of run through their community.

But things appeared to take a turn when Senator Daniel K. Inouye from Hawaii sent a letter to Metro asking them to “be responsive to the concerns and ideas of both residents and businesses located in Little Tokyo."

Yoshimura and Fukushima both said that the letter drastically improved the relationship between Little Tokyo and Metro.

“You have to stay on Metro the whole time. Otherwise, they’re going to forget about you,” said Yoshimura.

Which is not entirely their fault since they have so many projects to juggle, she added.

Plus, tunneling through the middle of downtown L.A. to connect two light rail lines is "just not an easy task,” said Roybal.

“It’s the density and where we are that really complicates things. You’re coming in after the fact. Everything is already all built out and there’s new projects on the horizon every six months or so," she continued. “If we were somewhere else with less people and less development, a lot of things would be a lot easier.”

Despite this shaky start, Roybal asserted that Metro appreciates the dialogue with the community. “We were very fortunate that they were very active and that they were willing to dedicate their time to this process,” she said. “Without the community support, you can’t move forward with the project.”

But Fukushima said this kind of situation should apply to all affected communities, rather than be unique for Little Tokyo. “It shouldn’t be special because we forced them. This is how they should do community outreach and community engagement.”

Fukushima said Little Tokyoites used to organizing to protect their own interests, citing the time they fought the city when it wanted to put a 512-bed jail next to a major Buddhist temple.

As the Connector continues with its construction, organizers like Fukushima and Yoshimura will be watching and waiting to see how all their efforts will pan out once the connector is completed.

"It’ll be great [for Little Tokyo] if businesses survive," Yoshimura said.

Roybal was more hopeful regarding the project. “Everywhere you look, there’s cranes. There’s a lot more people working and living in downtown. There’s a lot more family. There’s a new charter school," she said. "It’s pretty impressive, what’s going on now and this project will just facilitate that.”

Reach Staff Reporter/Photographer Benjamin Dunn here. Follow him on Twitter here.