Damsel: In Distress Of Being A Super Hero

Barbies and princesses make up a business worth over $4 billion today. Advertised in animated feature films, commercials, fast food chains and retail stores, the dolls frequently top wish lists made by girls as young as 3 years old. While many parents are growing increasingly discontented with the gender issues associated with princess and Barbie culture, one Southern California mother decided to create her own princess story for her daughter's fifth birthday.

"At three years old, my daughter was seduced in the culture, and I had problems with the messages," explains Setsu Shigematsu, a professor at the University of California, Riverside's Department of Media and Cultural Studies. "Although I never bought her any princess products, that only made her want them more and more, so on her fifth birthday I wrote a princess story about a princess that I would want her to emulate."

After presenting the story at her daughter's birthday party, Shigematsu received such positive feedback from parents that she continued writing. "Parents told me that these types of stories should be available," says Shigematsu.

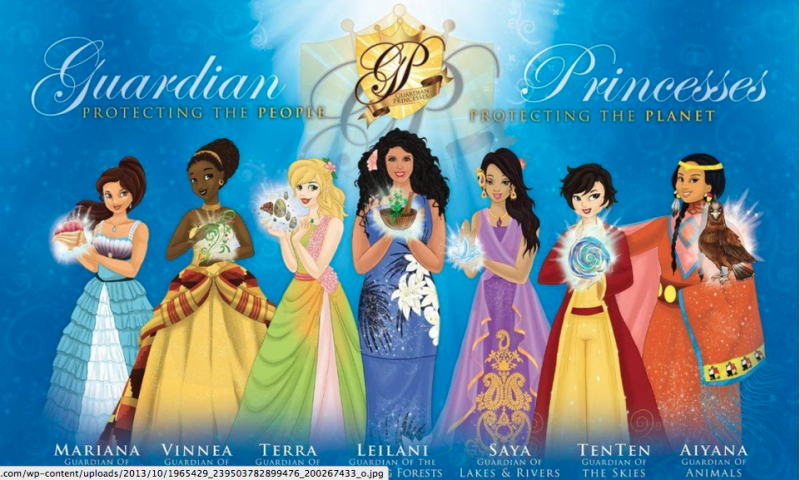

Shigematsu developed her story into a series known as "The Guardian Princess," about a group of princesses who solve problems, protect the planet and don't wait on Prince Charming to save them.

SEE ALSO: The Princess Effect: Are Girls Too 'Tangeled' In Disney's Fantasy?

Not only do Shigematsu's stories subvert gender norms, they challenge the eurocentric, heteronormative image of of princesses as well. Shigematsu wanted a paradigm shift, a shift that could change the role of the princess from the archetypal "damsel in distress" to the heroine.

According to Shigematsu, the stories are designed to teach both boys and girls how to protect people and the planet; each princess is the guardian of a different aspect of the environment, and each story is a parable about a current global issue.

Shigematsu sought to maintain the symbolic power of the princess, while shifting the cultural racial representation. There are seven diverse princesses representing seven different ethnicities: Latina, African, Pacific Islander, European, South Asian, East Asian and Native American.

According to the Census Bureau, over half of the children under the age of five are minorities, yet the dominant princess industry has a majority of white princesses and dolls. Within the last twenty years in children's literature, only 10 percent contain multicultural content, according to Lee and Low Books. Shigematsu's goal was to use these princess superheroines that could provide children with better role models, while teaching them to be empowered and inspired to be consciously aware of the environment.

SEE ALSO: Why Are We Obsessed With The Royal Couple?

Each of the princesses possess super powers and is the guardian of a certain aspect of the environment. The characters represent varried sizes and appearances that alter the heteronormative image ideal, and are presented as leaders and allies in their own right, without reliance on a traditional prince.

One particular princess, Ten Ten defies most-to-all stereotypes of gender norms. She refuses to wear a dress; she keeps her hair short, which is against her culture and she practices a martial art, which historically, is only for boys; in many ways she breaks the feminine model.

Shigematsu's daughter, Saya, not only loves the stories, but helps in the creative process as well.

"I help pick out the colors and drawings, and what the princesses should wear," she says.

"It's been wonderful to see my daughter and her friends get involved," adds Shigematsu. "We've been able to create this alternative universe of princesses."

Currently, Shigematsu is drafting new stories but hopes to turn "The Guardian Princesses" into an animated series.

Contact Staff Reporter Isaac Moody here.