New South L.A. Hospital Faces Criticism Over Delays, Lack Of Services

Juliana Barrios was bleeding to death on what should have been a joyous Christmas evening. The 24-year-old Pomona woman was the victim of a drive-by shooting and rushed by her family to the Martin Luther King Jr. Multi-Service Ambulatory Care Center in Willowbrook for medical help. A misguided attempt, as the facility does not offer trauma care.

She died in the parking lot.

Just yards away from Barrios, however, stands a brand new hospital. This state-of-the-art medical facility, with its steel and glass façade, had already wrapped up primary construction a month before Barrios was shot. But Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, which will serve 1.2 million residents when it eventually opens, won’t see a single patient until May 2015 – nearly 18 months after primary construction was completed, and three years after it was originally promised to be open.

It is unlikely the new hospital would have helped anyway.

Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital will not have a trauma center, a gap in services that raises serious questions in an area with a disproportionate amount of violence. The hospital will also open without a stroke or a STEMI center – meaning the facility will not treat heart attack victims. Additionally, the hospital will not offer pediatrics (a service provided by the neighboring Outpatient Center) or house medical residents, depriving doctors of yet another learning environment.

READ MORE: Community Reacts To New South L.A. Hospital With No Trauma Center

Described as "one of the most modern hospitals in southern California," the medical facility will be situated in an area where coronary heart disease, stroke and homicide are three of the five leading causes of premature death, but will be unable to adequately address any of those emergency needs.

Barrios’ death underscores the two main challenges with the oft-delayed, but now completed community hospital: getting the doors open and managing public expectations.

Erected on the skeletal remains of the shuttered Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center in South Los Angeles, primary construction finished on the all-new $284 million hospital in Fall 2013. It will restore medical services to an impoverished area of Los Angeles County left reeling after King/Drew closed in 2007 due to gross negligence, systemic fraud and preventable patient deaths.

READ MORE: Compton Medics Recall 'King King' With Fondness

Much of the rhetoric surrounding the new facility seems focused on exorcising the ghosts of King/Drew. Any utterance of the fact that the old hospital had a trauma center, whereas Marin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital does not, immediately sends officials straight toward talking points distancing the two facilities.

“We’re not trying to recreate King/Drew,” Dr. Mark Ghaly, the Director of Community Health & Integrated Programs for L.A. County Department of Health Services, insisted over the phone.

When a group of USC undergraduate students toured the hospital in March, County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas’ office tried hard to pivot away from the old hospital’s painful history.

“This is not the same hospital. This is an all-new hospital, we cannot stress that enough,” Ridley-Thomas’ communications director, Lorenza Muñoz, told the students.

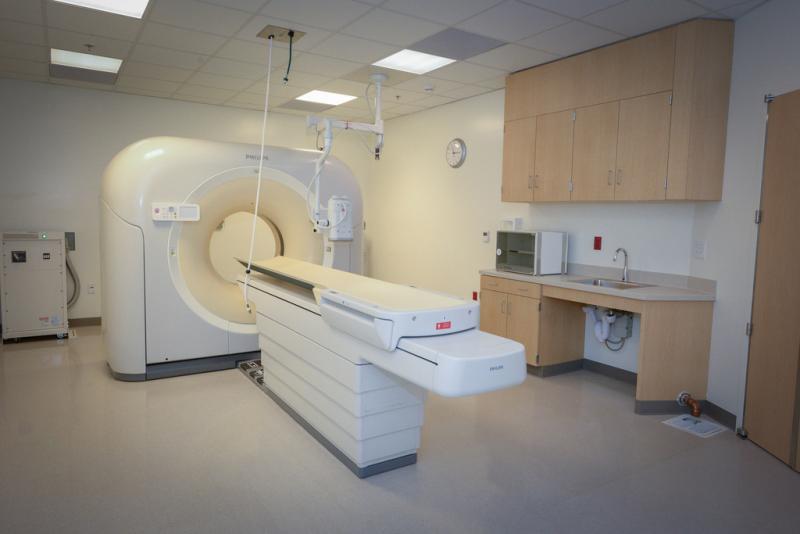

For now, the hospital’s only visitors are distinguished guests and students queuing outside to tour the glistening, but totally unoccupied, Inpatient Tower. On an early morning, you can catch county employees power-washing the front entrance for visiting patients who will not arrive for another year. The tarp has been removed on a statue adorning the exterior driveway. If you peek inside the hospital's glass windows, you can spy furniture, phones and even an MRI machine.

None of it will be in operation for another 12 months, astonishing some healthcare construction professionals: "It's not typical," said David Schmidt, chief operating officer for New York-based Skanksa USA. But through the county’s lens, the long-gestating hospital is seen as both deliberative and sensible.

READ MORE: Will A New South L.A. Hospital Mend Old Wounds?

According to Ghaly, the county’s goal is to provide a baseline of services to ensure high-quality healthcare access for an area of dire need as quickly and responsibly as possible. Trauma centers require an "extensive amount" of specialists and time to setup, further complicating immediate access to healthcare for South L.A. residents. But he reiterated that the county has the flexibility to revisit the issue down the line.

“The county is acutely aware of the health disparities in the community, and committed to answering those challenges. This is just the first phase for the medical campus. We see this as the first step in a long-term commitment to the community. Later phases assume expansion, and in that expansion, services can be revisited.”

For Los Angeles City Councilman Bernard Parks, the lone voice of dissent when the county disclosed construction cost overruns last year, that simply is not good enough. The promise to replace King/Drew with another, presumably better facility – a move he met with opposition – rings hollow.

“It's a slap in the community's face as far services needed,” Parks said, “This hospital is really just a high-priced clinic.”

“Anyone looking out for the residents and the users of the facility would not have made the decisions that have been made. From the beginning, the process has not been fair and it’s just been one lie after another, building and compounding.”

Things seemed to be heading in the right direction when the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development certified the 131-bed hospital to staff and stock the medical facility on November 31, 2013.

But the county and the hospital's non-profit operator, Martin Luther King Healthcare Corporation (MLK-LA), only reached agreement on terms of the lease last month. The prolonged negotiations puzzled outsiders, especially since the county itself helped spawn the non-profit operator, essentially choosing to lock horns with its own bureaucratic offspring.

Ghaly argued the complexity of the deal made it “next to impossible to work out in short order,” citing operating and financing provisions attached to the deal that made the 40-year lease agreement far more complicated than a simple land and building pact.

The lack of a lease agreement put the medical facility in a holding pattern for nearly six months, a scenario that “doesn’t make economic sense,” according to Glenn Alan Melnick, a professor for the USC Price School of Public Policy and an expert in health economics and finance.

“The minute the building is done, it should start operating,” Melnick added.

“We spent the necessary time to make sure that we’re managing taxpayer dollars appropriately, and taking time to articulate provisions that are complex, new and really important,” Ghaly responded. “The amount of time is not a cause for concern, but reflects a level of due diligence on behalf of the county.”

Ghaly also contends many of the higher level details from the 2009 coordination agreement between the county and its partners had never been mapped out until negotiations began. “Fifty to 60 people touched that document; multiple law firms and parties,” Ghaly said. “This is not just a lease, it’s really a blueprint for a productive relationship.”

READ MORE: Not Just A South L.A. Hospital: An Artful Representation Of The Power of Community

But James Guy, director of facilities at USC Verdugo Hills Hospital, could not ever recall seeing a similar situation. “People don’t do that. You usually build a hospital for a tenant, and then the tenant receives clearance to open,” James said. “The building must meet the state requirements, but only after the tenant has been set up.”

David Schmidt, the chief operating officer for Skanksa, one of the largest healthcare construction firms in the world, found the timetable somewhat questionable.

“You just never ever would have started unless you had secured a lease. That’s the part that, from a business perspective, would never ever happen," Schmidt added.

“They would have the operator in position, within a year of opening you would have already brought in critical staff, and move planning would have happened. By nine months before opening, you’d bring in critical equipment, so it’s ready to go. So once you’ve got substantial completion – you’ve got it ready to go.”

It is difficult to grasp why this fully built hospital sits unused. The hospital’s CEO, Elaine Batchlor, was hired in 2012. Most of the management staff was brought on board last year. And according to Batchlor’s own presentation to the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce, equipment and furniture was selected, some of it purchased, in March 2013. The county was already moving in furniture before the ink was dry on the lease agreement.

John Fisher, the hospital’s chief medical officer, said selection does not necessarily mean equipment is installed right away.

“Selection and purchase, shipment and installation are completely different,” Fisher said. “If you’re building a house, you can go and pick out what kind of furniture you might want even though your house won't be finished being built for another year. Actually having it purchased and installed, that’s completely different.”

Fisher – sitting in front of a dry-erase board detailing the yearlong rollout of electronic medical services – is adamant that the additional 12 months is needed to hire and train staff to provide a level of care MLK-LA is comfortable with. He maintains the hospital is on track to open its doors next May.

“I think that’s a reasonable amount of time,” Fisher said.

To an outside observer like Schmidt, the hospital’s construction and management history almost left him at a loss for words.

“I’ve never seen this before. It’s not typical. You just wouldn’t do that. This is an issue with the public entity’s management of the project. I’ve never heard of something like this occurring,” Schmidt told Neon Tommy.

But Ghaly feels those comparisons are unfair, simply because there’s “no model to base the hospital on.”

“There’s no baseline, there’s not another hospital you can look to as a guide to see who or what they have done. This public-private partnership is not only unique to L.A. County, but there a few models like it anywhere.”

The decision to allow an independent non-profit to operate Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital was the result of the county’s ambitious plan to restore medical services to constituents in South Los Angeles after the bitter and very public closure of King/Drew.

READ MORE: The Disparity Of Healthcare Services In L.A. County

Eager to avoid the failings of King/Drew, the county and the University of California Board of Regents formed a partnership to engineer a not-for-profit organization, MLK-LA, to oversee the hospital. The county would provide the money, UCLA would provide the expertise and MLK-LA would make sure services were reliably delivered.

The landmark agreement was made in 2009, with a target date to open the new hospital sometime in 2012. Two years after that date, South Los Angeles residents are still waiting.

And if Batchlor is making the same amount as her predecessor – interim CEO Melayne Yocum's salary was $328,000, according to the hospital's most recent publicly available tax filings – the hospital’s chief executive could earn roughly $1 million before the facility sees a single patient. The hospital did not directly disclose Batchlor's salary after multiple media requests.

Batchlor is a key cog in a hospital management structure touted as a private-public partnership by the county, but that label is rather dubious, according to a source with knowledge of the hospital’s staffing and wished to remain anonymous.

“The private partnership does not exist. It's MLK-LA. That's the ‘private’ end of the partnership, which is really just made up of people from UCLA,” said the source, who is highly fluent in medical staffing across Southern California.

That same person also voiced concerns that MLK-LA has been “less than transparent” during this process and said delays are tied to difficulties in getting the UC system to fulfill its promises.

“They're missing the structure of their medical staff. They don't have infectious disease doctors, they don't have OB/GYN, they don't have cardiologists, etc. This isn't what was promised, and now everyone's scrambling to fill those spaces.”

Chief Medical Officer Fisher fired back, however, saying UCLA has provided all the necessary services originally agreed upon – such as quality oversight, performance improvement and staffing.

“Those were the core expectations that were within a coordination agreement,” Fisher said. “And I think based on everything we’ve seen so far, UCLA has gone above and beyond to fulfill those. I don’t see any actions on their part as far as pulling back.”

The last vestige of King/Drew – the ambulatory center Barrios died outside of – is essentially being transferred into the adjacent Outpatient Center after a much-ballyhooed ribbon cutting ceremony on May 28. But Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas will have to wait at least another year to pull out the oversized, ceremonial shears to cleanse the campus of its troubled past and finally open Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital.

Conversations with county and hospital officials often end up with both parties reiterating that comparisons to the preexisting hospital are unfair; this hospital is absolutely, positively not the old King/Drew. Occasionally there are the slip-ups in conversations and branding – like when the hospital’s chief information office, Sajid Ahmed, referred to the hospital as “MLK 2.0” in a presentation to health professionals.

But in a prolonged effort to not repeat past mistakes, the county and the hospital may have created all new ones. At the end of the day, the doors will open with the notion that a well-run and brand-new hospital offering fewer services than the old, but negligent one is a good tradeoff. For some in the community, that's a hard pill to swallow.

Parks, for all his condemnation, ultimately worries about how many lives the hospital will cost by forcing trauma and stroke victims to continue to travel all the way to St. Francis Medical Center or Harbor-UCLA Medical Center – three and 10 miles away, respectively – once Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital eventually opens.

READ MORE: Non-Emergency Medical Service: What Happens When South L.A. Calls 911

Both the hospital and the county concede that publicity and education will be a critical to avoid people from bringing trauma victims to the facility. But Ghaly said what's important is what the hospital actually offers – urgent care, OB/GYN, general surgery and other medical services.

“In discussing the [lack of] trauma center, we often overlook the services the hospital will provide to help the community. And we’re looking at solving healthcare challenges facing the community in innovative ways, not recreating the old hospital,” he added.

For Councilman Parks, this is unacceptable: “The real medical needs in our community are trauma and heart-related. Those are things that the community has no answer for.”

Editor-at-Large Max Schwartz contributed to this story.

Contact Editor-in-Chief Will Federman here. And follow him on Twitter.

Contact Staff Reporter Matthew Tinoco here. And follow him on Twitter.