Downtown L.A. Education Behind The Curve To Population Demand

Metro Charter Elementary School launched with 16 students inside one of the hospital’s downtown L.A. buildings last September, proving that quality education can happen anywhere.

Now five months later, about 80 kindergarten, first- and second-graders noisily line up in front of small multi-colored cones before entering one of five classrooms for a full day of project-based learning in the rundown hospital.

Pande ushers his daughter into class, watching her join the lively circle on the floor. Walking into what once was a hospital hallway, he explains how he and other parents won approval for the new school. They weren’t happy with their choices for public elementary schools, and private schools were too exorbitant. The nearest school, Ninth Street Elementary, ranked as one of the lowest performing elementary schools in California before it was closed for renovations. Para Los Niños, a charter school at Seventh and Alameda Streets, has a persistently long wait list.

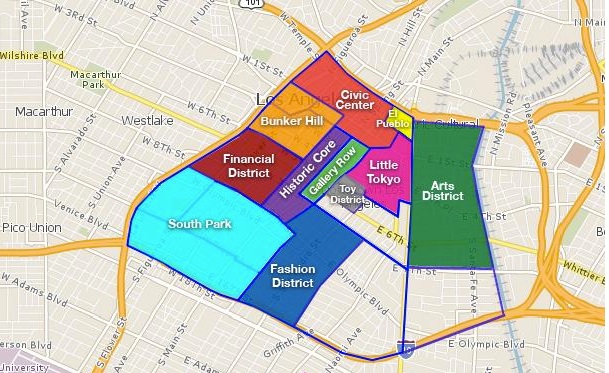

He joined other downtown parents in successfully petitioning the Los Angeles Unified School District to approve Metro Charter in the South Park-Historic Core area. They overcame resistance from a few school board members, who argued the school would gentrify the area and not welcome longtime residents.

“We wanted something within our community that was open, walkable and free for everyone,” said Pande. “There was really no viable public option in this area.”

When asked where he would have sent his daughter if Metro failed to take off, Pande smiled and said bluntly, “We didn’t have a plan B — it was this or nothing.”

Colorful construction paper drawings brighten the old hospital’s fluorescently lit hallways. One by one, the school is adding more classrooms and testing out new teaching methods.

Second-graders proudly showed off miniature papier-mache downtown buildings and roads to replicate their stomping grounds. It was just another example of downtown L.A.’s developing reputation as a “young family” destination.

Educating students about urban development is a core part of Metro’s curriculum, said Principal Maricela Barragan, as she settled in a child-sized red plastic chair for the interview. Her office is still being built.

“Kids are still moving in, and we’re in the process of getting our furniture down here,” laughed Barragan. “But it’s refreshing. We don’t have any scores on us. We’re so new that we’re learning every day.”

READ MORE: "Downtown L.A.'s Economic Development Is A Mixed Bag"

Like Metro Charter, downtown Los Angeles faces its own transformation. The industrial, low-income sprawl is now rife with luxury loft apartments, upscale restaurants and trendy bars.

Ten years ago, about 10,000 people lived downtown. Now, it's closer to 50,000. As more families move into the business district, more children need schools. A 2011 demographic study showed almost seven percent of downtown residents had children under the age of 5. Another five percent of homes had children between 5 and 18. That means nearly 4,000 more children are running around downtown’s neighborhoods.

At Para Los Niños, a few miles away, close to 90 percent of all students are Latino. Nearly all live at or below the poverty line.

Barragan said her school is much more diverse, both demographically and economically. Parents range from doctors, architects to single moms who work three minimum-wage jobs. But all of her families live in downtown.

“People have this misconception that we were going to cater to one kind of family, that kids would be coming in from one demographic,” said Barragan.

But they don’t. Metro’s classrooms look much different than other downtown schools. The class sizes are smaller, the diversity rank is higher and most students are at grade level in reading and math. Out of 80 students, 23 are English learners. Of all first- and second-grade students, only four are below average.

Oddly, these stats are why the charter school garnered criticism last year. School board member Steve Zimmer voted against the school, saying it wouldn’t help downtown’s homeless or poor students.

Pande dismissed the accusation, pointing out Metro Charter as one of the area’s most diverse schools — economically, socially and ethnically — representing the changing face of downtown.

Even though downtown’s demographics are spreading — 37 percent is Latino; 16 percent white; 21 percent Asian and 22 percent black — the public schools still cater to mostly Latino students.

Ninth Street Elementary is about 75 percent Latino while both Tenth Streeth Elementary and San Pedro Elementary are close to 100 percent.

“The problem with L.A. public education is that schools may serve minorities, but they aren’t diverse. They serve mainly one ethnicity,” said Pande. “This makes parents self-segregate.”

Diversity is a core principle of Metro’s mission. “We were aggressive in finding students,” said Pande. “We went out to community groups, churches, Skid Row, making sure people from different backgrounds know about our school.”

About half of the charter school’s 80 students are Title I, meaning schools receive more resources from the federal government. The other half comes from middle- and upper-middle class families.

Barragan notes the school’s great capacity for growth. She hopes to have room for 250 students by 2016 and give them a space to call their own.

The public Ninth Street Elementary is another. Once a collection of sagging bungalows, the school just unveiled a new $54 million, 78,000 square-foot educational complex, complete with two dance studies, Wi-Fi and five high-tech boards thanks to funds from bond measures and grants.

But downtown needs more than three new or modernized schools to serve a burgeoning student population.

“Downtown is so underserved and has gone such a big transformation in the last decade,” said Pande, who lives at 7th and Olive. “But everyone outside downtown is just waking up to all the changes here and they are so far behind.”

This story is part of a Neon Tommy special on the revitalization of downtown Los Angeles. Click #reviveDTLA for more.

Reach Editor-in-Chief Brianna Sacks here.