Venice Beach Architecture: Lessons In History, A Revolution In Art

As part of the Pacific Standard Time's "Curating the City: Modern Architecture in L.A." volunteer docents from the Los Angeles Conservancy brought their knowledge to several architectural sites. The showcase provided a glimpse into Venice's past as well as a closer look into the sources of its unapologetic creativity. A number of the architects that transformed the sleepy beach town were on hand to reflect back on the halcyon days.

"In a community that's so artist-driven, there's a lack of fear," said architect Brian Murphy, nicknamed the "Bad Boy of Architecture" by the Los Angeles Times 25 years ago and the man Dennis Hopper turned to when he needed a new house. "People don't feel obliged to make the mother-in-law happy."

Besides serving as a history lesson, the event carried more urgency for some of the volunteers.

"In a couple more years, this could be up for demolishment," said Jerome Robinson, the docent at Windward Circle, pointing out the surrounding buildings that aren't currently on a preservation list. But it's about more than just preserving the buildings, he adds.

"Buildings, to me, are about people also. It gives a sense of community," he said.

SEE ALSO: Venice Skate Park- A Birthplace Of Skateboarding

In addition to their stunning architecture, history is infused in each of the buildings on Windward, designed by Steven Ehrlich in the 1980s.

The "Race Through the Clouds" building is reminiscent of the massive rollercoaster that was demolished in 1923. Even the curbside bike racks evoke the curves of a coaster.

The Ace Market Place likewise resembles the dredging machines that dug the original Venice canals in 1905 before being filled to accommodate automobiles in the 1920s.

Where that giant rollercoaster once towered over a serene lagoon and Italian-inspired canals cut through the city, the Windward Circle roundabout now hosts a steady stream of cars with surfboards poking through their windows.

Standing there on Windward Circle, you can’t help but feel a mix of awe and dismay.

Like many, I've passed by these structures dozens of times, but I've never really bothered to learn about L.A.'s past. Living in a city that's constantly under some multi-year construction plan, it's easy to only look forward.

Thankfully for Venice, Ehrlich and his contemporaries had the foresight to consider history when building what remains today. In fact, it could be argued that the city owes a significant part of its creative spirit to those who regarded art and architecture as one and the same.

It was a combination of cheap land and a desire to "live on the edge" that first attracted Venice's most revered architects in the 1970s. What set them apart was that they thought like artists.

Frank Gehry may have put it best in a quote published in Architectural Record in 1976:

"I try to rid myself and the other members of the firm, of the burden of culture and look for new ways to approach the work. I want to be open-ended. There are no rules, no right or wrong. I'm confused as to what's ugly and what's pretty."

That mentality paved a new way for architecture, much to the indignation of the traditional architecture community, says Frederick Fisher who began his career under Gehry's tutelage. Since the community already embraced the avant-garde, Venice became their playground.

SEE ALSO: What Los Angeles Could Have Been

At a panel discussion mid-tour, architects Steven Ehrlich, Frederick Fisher and Murphy discussed the Venice they observed in the 1970s, the possibilities it offered and why they were so captivated by it.

Murphy, known for his use of unconventional materials, designed the home for Dennis Hopper. The facade of Hopper's house is an austere corrugated metal while the inside involves more play with light and transparency. A glass bathtub, a glass balcony and a glass floor in the upper floor bedroom are some of the standout features.

Fisher also signals the irony of where the panel was hosted. The Westminster Elementary School lawn had been the site of a beautiful craftsman auditorium, which Los Angeles Unified School District tore down in 1982, he says.

"This was the site of one of the greater lost preservation battles," he said. "And you can see what good use they've made of the site." The lawn is surrounded by chain-link fence with little indication of what its purpose is.

"But apropos to that, I don't think that building ever would have been allowed to be torn down had that been today," noted Steven Ehrlich, the architect of Windward Circle's buildings.

Tours like the one in Venice on Saturday are instrumental for ensuring more historic sites in Los Angeles stay preserved, says Linda Dishman, executive director of the L.A. Conservancy in a separate interview. While none of the buildings on the tour are currently designated for demolition, they are also not under protection, she says.

"It's one thing to read about these buildings in a book or see them in a magazine, but when you actually come into a house, and see the way the light comes in, that's something you can't get from a book," Dishman said.

SEE ALSO: Venice Beach Boardwalk Vendors Search For Meaning Of Art

Beyond being colorful landmarks, the buildings in Venice largely contribute to the city's story.

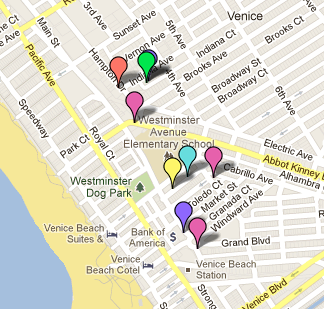

There's the Architecture Gallery on San Juan Avenue where The Eagles gave their first public performance in 1972. The building later housed "WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing," a publication that captured the bawdy anarchy of L.A.'s 1970s culture.

There's also the United States Island, the triangle bordered by Windward Avenue and Cabrillo Street, where each small vacation house built in 1913 is named after a different state. The palm trees lining the street are said to be 100 years old.

The Venice architects may have done more than they realized in drawing a connection between a building and a piece of art. In fact, it may be that connection that solidifies their preservation later on.

But, as Dishman puts it, hands-on participation from the public– with people like myself gazing at Windward Avenue on a Saturday afternoon, feeling remiss over never learning about the city's history before– may be what's most vital.

"For people to experience the building's space is an important element in getting people to be passionate about their preservation," she said.

Find more Neon Tommy coverage on Venice here.

Reach Managing Editor Paige Brettingen here. Follow her here.