Deconstructed: Tuition, Endowments and Educational Justice

With all the talk recently from Undergraduate Student Government, USC Forward, and others regarding tuition and educational justice at the University of Southern California, it’s important to know what that entails. (Fair warning: it’s a bit complicated.) Let’s start with the basics.

What is a tuition freeze and why does it matter?

A tuition freeze is exactly what it sounds like: a policy that freezes tuition at its current amount. If USC were to freeze its tuition right now, it would remain at $24,732 per semester for undergrad students.

There are several reasons why a university might freeze its tuition. Students whose tuition is frozen are better able to plan their finances moving forward. Universities, too, are forced to budget within their means, eliminating what may be considered unnecessary spending.

This awareness of tuition costs seems to be most concentrated among public university systems. In 2013, for example, the Washington state legislature froze tuition at its public universities after it had “nearly doubled” over the four previous years during the recession. And in New Jersey, the state Assembly passed a bill in 2014 that would freeze tuition at all universities in the state with the exception of Princeton.

Speaking of Princeton, the university is one of six Ivy League schools that have a policy of not charging tuition to students with incomes below a certain level — typically about $60,000. The others are Brown University, Columbia University, Dartmouth College, Harvard University, and Yale University.

It’s worth mentioning that some of these universities offer financial aid solely based on need and never for academic or athletic merit.

Sounds great! Why not freeze tuition?

All colleges and universities, public and private alike, need funding to maintain their services. When the institution becomes more expensive to operate, that funding needs to come from somewhere.

In the University of California system, for example, the board of regents approved tuition increases up to 5 percent a year for five years in response to rising benefits costs, increasing employee pay and a growing number of faculty and students. Without adequate additional funding from the state, the UC system had to bump up tuition to make up for the budget shortfall.

For a private university like USC that has planned its budget around regular tuition increases, removing that additional funding could put planned expenses and expansion into jeopardy. To the university’s credit, USC Financial Aid Dean Thomas McWhorter pointed out that the university’s tuition increases are “near historic lows,” at an average increase of 4 percent annually over the past 5 years. For the last 50 years, the overall average annual tuition increase is 7.4 percent, McWhorter said. Keep in mind that a 4 percent increase in USC tuition today amounts to nearly $2,000 per school year, while a 7 percent increase 50 years ago would have been a hundred dollars or less. Both rates are higher than today’s dollar inflation rate of less than 2 percent year-over-year.

So… where do my USC tuition dollars go?

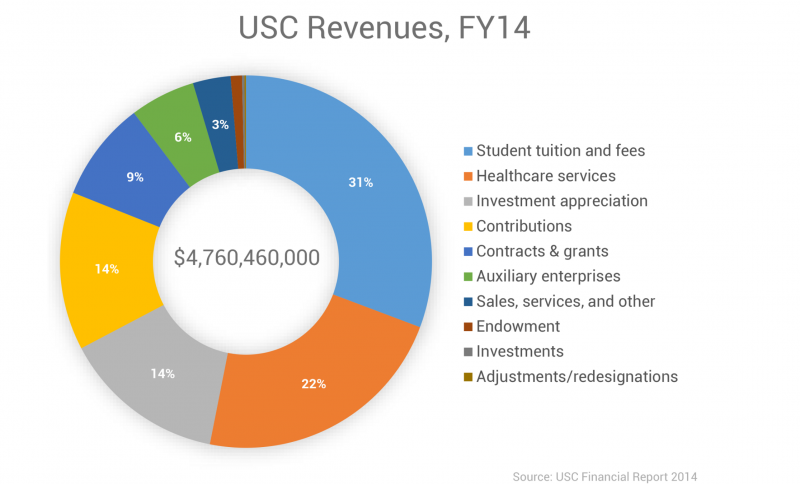

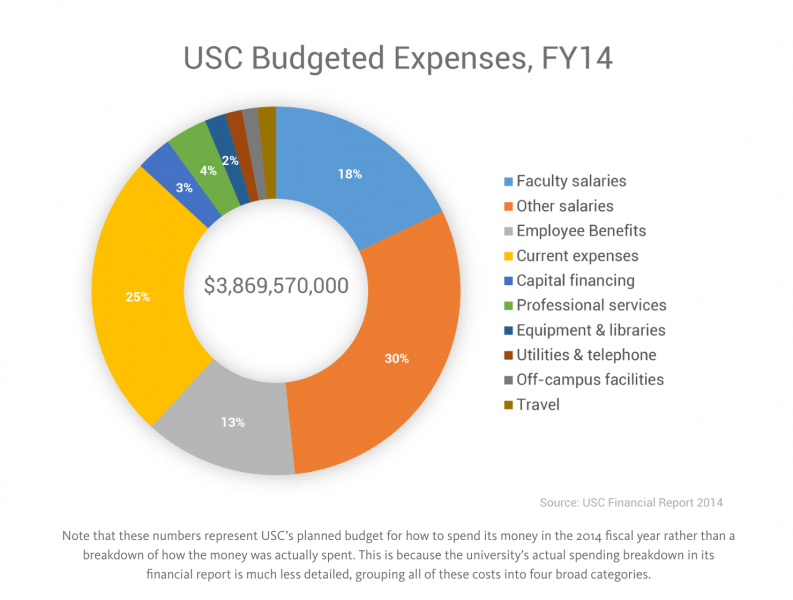

USC’s 2014 financial report — the most recent one available — indicates that the university brought in roughly $1.6 billion in student tuition and fees for the school year ending spring 2014 (about $120 million more than the previous year). Tuition and fees comprised roughly 33.7 percent of the university’s revenues for that year, with total revenues of about $4.8 billion.

USC then spent about $3.7 billion that year, with the majority — approximately $2.3 billion, or 62.8 percent — going to “educational and general activities,” a category comprised almost totally of employee compensation and benefits. This left the university with an “increase in net assets” — a profit — of a bit more than $1 billion (this includes income and appreciation from the endowment, but not contributions to the endowment).

READ MORE: Worker Delivers Tearful Plea To USC President To Increase Poverty-Level Wages

In that year, USC spent just over $440 million on need- and merit-based financial aid, less than half of the amount it eventually profited. McWhorter said that the university has worked hard to “maintain affordability, while increasing services to students, such as administering one of the largest financial aid programs in the country.” He pointed out that “USC works with families to meet 100 percent of the USC-determined financial need” and that the university’s financial aid department “provided special outreach and individual counseling to hundreds of USC students each year.”

But what about the endowment?

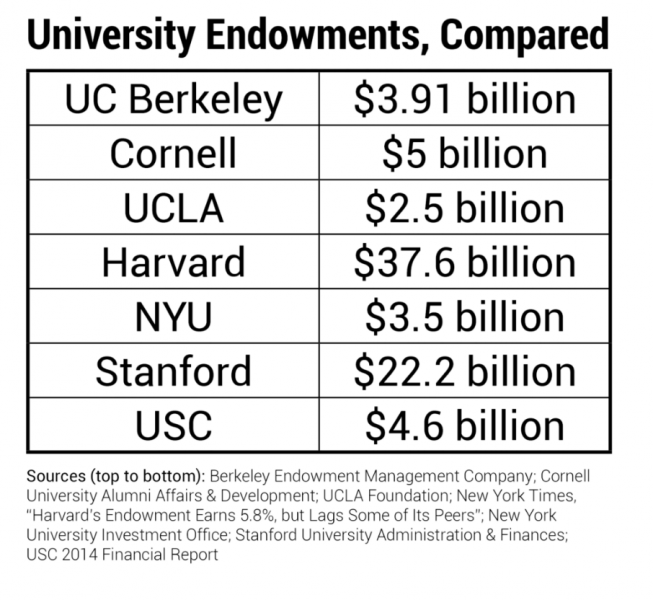

Endowments are generally used to fund a university’s operating costs that aren’t covered by other sources of income (i.e. tuition). They’re formed from money or property given to the university that is then invested to enable the endowment to self-sustain and continue to grow itself. Only a small fraction of endowment funds are ever used to actually fund something, so an older university would naturally have a larger endowment solely by virtue of having more time for the endowment to grow itself.

As Harvard president Drew Faust explained in an episode of the podcast Freakonomics, endowment funds are often “legally bound to certain uses.” The idea is to use the income from an endowment gift to not only fund something in the short-term but to find a way to preserve the gift “in perpetuity.”

USC’s endowment at the end of fiscal year 2014 amounted to $4.6 billion, and no more recent figures are available. Of that, about $3.2 billion was “restricted” in some way, which means that the funds could only be used for their designated scholarships, faculty support, or programs.

The University of Southern California divides endowment donations into “shares,” and the amount of money the university spends out of the endowment is a per-share dollar amount. The university’s rule is to keep this amount between three and five percent of the share’s market value. Explaining how it arrives at that number is a little complicated, but the end result is that the appreciation and investment income the endowment accrues far outpaces how much is spent.

READ MORE: California State University Students Could Face A Two Percent Annual Fee Increase

The university’s Campaign for USC, a multi-billion dollar fundraising campaign launched by university president C.L. Max Nikias, has purportedly raised $4.6 billion since its beginning in the fall of 2011. The initial goal was to raise $3 billion for the endowment and $3 billion toward “immediate support for academic priorities, capital projects and infrastructure.” However, according to the university, only about 34 percent of the funds raised so far — approximately $1.6 billion — have gone toward the endowment.

Tracey Vranich, USC’s Vice President for Advancement Services, said that the Campaign for USC has so far raised $221 million for the scholarship endowment, an amount that will accrue value over time. Remember that only a small fraction is paid out each year.

This makes the tuition-endowment relationship slightly more complicated. While the endowment is increasing (and the amount of university spending supported by the endowment is increasing with it), it is also true that tuition is increasing and the university’s expenses are increasing. It is unclear what the net effect of all these increases is, as the university does not make its current budgets publicly available. But given that the plan is for tuition to continue increasing, it doesn’t seem that the budget favors affordability.

What is USG trying to accomplish?

On September 14, USC Undergraduate Student Government posted a charton its Facebook page illustrating how USC tuition has increased exponentially since 1954 and crafted a survey to gauge how the tuition increases have affected students.

According to USG President Rini Sampath, the survey responses “clearly indicated the majority of our student body is dissatisfied with tuition increases and the current lack of transparency.”

Sampath recounted emails she received from students who purportedly were forced to skip meals or to leave the university because the increasing cost of tuition became too much for them.

As for what USG plans to do, there are two goals: to increase accountability regarding where tuition dollars go and to make USC more affordable, ideally via a tuition freeze.

On the accountability front, Sampath hopes to make the tuition increases more transparent. If tuition is going to increase, she said, students should know why.

“I know they publish a financial report at the end of the year, but students don’t know how to access these reports or how to parse through them,” Sampath said. “How can we make it simple and easy to understand for students? If we can even create a website where students can go online and see where their tuition dollars are going, which departments it’s going towards, I think it would give students a peace of mind.”

READ MORE: ‘Is My School Worth The Price I’m Paying?’

In terms of affordability, Sampath hopes for a tuition freeze paired with a serious reevaluation of how attending USC can be feasible and affordable.

“I think that we should take a look at what we are doing for students here at SC,” Sampath said. “I’d love to see some type of plan for the future so that USC is making sure every student we accept into our university is actually able to go here, because I think education is a right, not a privilege.”

Why does affordability matter?

The cost of college is often crippling, and that’s a fact, not a partisan issue (both Democrats like Hillary Clinton and Republicans like Marco Rubio have proposed plans to fix the college system). What makes high college costs dangerous is they prevent students from attaining the best of their potential, whether it’s by saddling students with debt or scaring them away from the best education they deserve.

To Sampath, this is a big problem and one that needs to be solved as soon as possible.

“I believe we are losing out on some of our best students because they’re having to transfer out of USC or they’re not coming to USC because of the cost here,” Sampath said. “If we’re truly a nonprofit organization aiming for higher rankings and [to be] the best institution that it can be, I think we should be looking for those incredibly smart minds that come from communities that are typically not represented. Higher education cannot become a space for just the 1%. It needs to be a space for all students, and I think we’re missing out on some of those remarkable students right now.”

What happens next?

This issue is not something that can be resolved quickly, but it’s not without support. Aside from Undergraduate Student Government, groups like USC Forward are also battling for what they consider greater fairness both in the tuition the university charges and how it is spent.

Tuition is skyrocketing. Faculty are struggling. WTF are we paying for? http://t.co/NmodRgHKkB #FightOn #PriceWePay pic.twitter.com/z8dv4c4Lx4

— USC Forward (@USCForward) October 7, 2015

After gathering the results of its survey, USG met with USC administration to discuss the “Value of a USC Degree.”

“As a collective student voice, we were able to properly convey the frustration our student body has felt regarding the lack of transparency of where our tuition dollars are going,” Sampath said. “The meeting on the ‘Value of a USC Degree’ is just step one in having student concerns heard and addressed. As USG, we are committed to bringing the student perspective to the table with our university administration so we can improve the collegiate experience for all.”

It’s impossible to know what, if anything, will change. But Sampath believes the University of Southern California does listen to what students say. And the current clamor for something to change is certainly hard to ignore.

Reach Staff Reporter James Tyner here or on Twitter @jamestyner_