The Body, Painted And Performed: Feminist Artists Who #FreeTheNipple

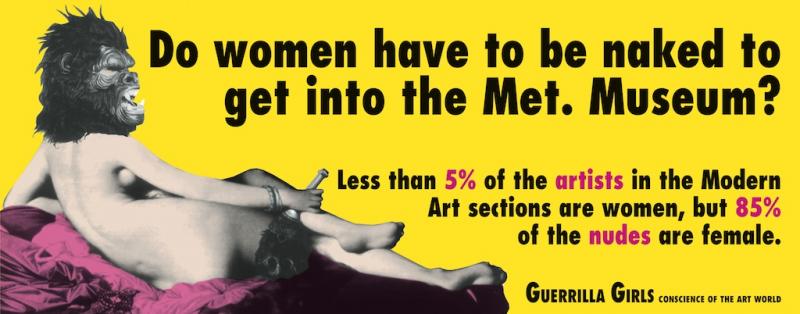

Less than 5 percent of the artists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Modern Art sections are women, but 85 percent of the nudes are female. That statistic is jarring enough on its own; but now picture it on a bright yellow billboard also featuring a naked woman with the head of a ferocious fanged gorilla.

That memorable image is by the Guerrilla Girls, a group of feminist artists who did a “weenie count” at the Met in 1989. Their work showed how the female body has always been one of art’s most popular subjects, even though women artists historically had little chance to represent their own bodies.

READ MORE: 17-Year-Old Organizes #FreeTheNipple Protest, Is Cooler Than Us

Systemic inequalities still fester in our art institutions – the Guerrilla Girls redid their weenie count in 2012 and found the numbers of female artists and female nudes at the Met hadn’t really changed. But over the past century, more and more women have busted through the art patriarchy to make art that is about – and often takes as its form – the female body.

The works exist somewhere between the worlds of personal expression and political protest. They happen in tandem with, and sometimes overlap, movements like today’s Free The Nipple and 400 Pueblos Movement.

The 600-year stretch from the Renaissance to the 20th century was, unquestionably, the heyday of rich white dude art, as well as the heyday of lady nudes. Even up to the end of the 19th century, the French Académie favored paintings featuring busty Rubenesque women (painted by men, of course).

A few women toyed with the system before the turn of the century – like Impressionist Berthe Morisot, who liked to paint herself in what some people think is drag – and the first half of the 1900s brought a sprinkling of others.

Dada artist Hannah Hoch was basically the first Riot Grrrl. She made collages that used pictures of women’s body parts in subversive ways, like legs covered with a pair of creepy old man eyes. “Höch was also a staunch feminist and an early supporter of reproductive rights, often marginalized for her manly dress and bisexuality,” says Carey Dunne at Fast Company. “In her piece "From an Ethnographic Museum," naked breasts paired with mustachioed tribal masks lambasted traditional sex roles in the [Weimar] Republic's repressive social climate.”

Hoch’s works are about, among other political criticisms, examining and reclaiming the huge swell of images around her at the beginning of mass media. Her twisting of traditional and commercial depictions of female bodies formed a base for feminist and appropriation artists in the second half of the century.

And, of course, no conversation about female bodies in art would be complete without a mention of Georgia O’Keeffe’s notorious flower paintings, which many have interpreted as…not flowers.

O’Keeffe claimed until the end that her works weren’t meant to look like lady parts, but most critics don’t buy it. "It now seems abundantly clear that, in spite of her vehement denials, O'Keeffe meant some of her paintings (not just the flowers) to look vaginal," SMU art history professor Randall Griffin writes in his book “Georgia O’Keeffe.” “O'Keeffe's great achievement was that she created a fearlessly candid - though metaphoric - representation of the female body, one entirely different from the tradition of female nudes painted by male artists for a male audience."

Despite Hoch’s and O’Keeffe’s contributions (among a handful of others), the Modernist period was highly male-dominated. Women artists didn’t exist in large numbers until the 1970s, which were phenomenally fruitful years for women to make art about their bodies, as the second wave feminist movement bloomed in tandem with an explosion of performance and body art.

Women artists in the ‘70s not only created art modeled after their bodies; they also made their bodies themselves the art in new works that explored and challenged the social constructions of the female body.

Ana Mendieta started her “Silueta Series” in 1973, in which she used her naked body in a variety of different ways, from rolling around in the dirt to holding a freshly decapitated chicken by its feet and covering herself in its blood. She explored the relationship between her [female] body and the Earth in a series of “subversive self-portraits that played with notions of beauty, belonging and gender,” says Sean O’Hagen at The Guardian. “She evoked the power of female sexuality as well as the horror of male sexual violence.”

She says that Wilke was not only exploring her objectification in the art world, she was also taking control of it by becoming an active subject in her own representation. “By enacting herself as a subject (the maker) as well as the figure in the artwork, Wilke could suture together woman/object and woman/subject—at the time, in that context (1970s New York art world), this was super empowering,” says Jones.

Today, the context surrounding women’s art has evolved, but women continue to challenge representations of their bodies through art and cultural production.

“Clearly today more women (at least white middle class women in first world countries) have more agency than in previous eras,” says Jones. “Whether or not we think a female pop star gyrating almost naked, viz. Miley Cyrus in ‘Wrecking Ball,’ is empowering herself is up to debate…nonetheless we have more access to the media (barely, but still) and to our own self imaging, or at least more awareness of how the structures of objectification work.”

Social media and the advent of the selfie have allowed for more female “self-imaging” of all types, including subversive actions like social media movement #FreeTheNipple (of which Cyrus was, unsurprisingly, an early adopter). Women post pictures of their nipples with the hashtag #freethenipple in protest of Instagram’s no-lady-nipple policy and laws in many U.S. states that prevent women from being topless in public.

“Feminism says that men and women should be treated equally in all aspects of society,” says Jamie Katuna, who recently attended a Free The Nipple topless rally at UCSD. “But we won't be equal if our bodies are constantly being controlled and policed on social and legislative levels while men's bodies are not…I exist in a woman's body, and I should have the same rights to show it that a man has.”

Emerging artists like Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst explore this tension in their “Relationship” photograph series, which documents their lives as “a transgender couple whose bodies are transitioning in opposite directions.” And just this week, the photos Annie Leibovitz shot of Caitlyn – formerly Bruce – Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair have started a firestorm of conversations surrounding the cultural representation of transgender bodies (and how that representation changes based on race and class).

The media explosion surrounding Jenner’s new identity shows the debate over women’s bodies and their representations intensifying again under a new generation of networked, sometimes not-traditionally-female feminists. Like the artists before them, these women are continuing to push the boundaries of self-imaging into new and controversial territory.

Contact Editor-in-Chief Gigi Gastevich here.