Q&A with Adelle Waldman: Novel Talks At Neon Tommy

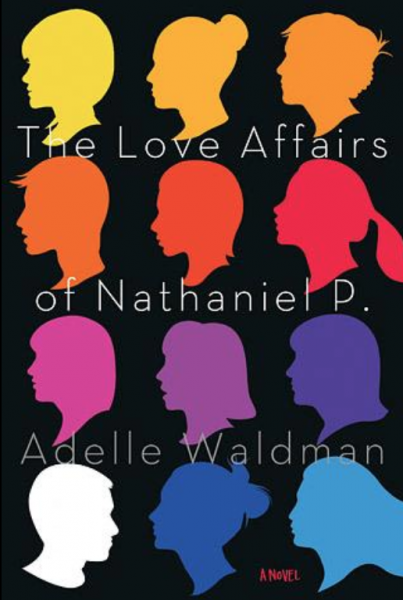

If you’re looking for the modern Jane Austen, look no further. Adelle Waldman’s first novel, "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.," is not afraid to dissect every fear you have about the modern relationship. Praised by NPR, GQ, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times (just to name a few), "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P." is truly deserving of the literary hype. The novel's protagonist, Nate, may not be as likeable as Darcy or Heathcliff, but you will recognize aspects of him in every one of your ex-boyfriends. I was lucky enough to speak with Adelle Waldman for Neon Tommy about her career and the process of publishing such a successful first novel.

It’s been two years since "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P." released. How does it feel to have such success with a first novel? And in what ways has it changed your feelings on the publishing process as a whole?

In a lot of ways it’s been amazing, I mean in every way it’s amazing. I spent about four years of writing the novel and then another year after it was in the hands of my publisher (and I’d only get it back to make small copy edits). And during those four years I was working mostly as an SAT tutor. And while "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P." is my first published novel, I had written a novel before that wasn’t published. Which is actually something I now look back on as a stroke of luck. The first novel is not so terrible that it could have never been published, but now I feel like its better in a drawer. Though I did learn a lot about novel writing from that experience.

I was actually devastated when that novel didn’t get published. It took me a while to see it as perhaps not as strong as it could be. And I learned that if I want to do this thing, writing novels, that I had to find some kind of internal strength to pursue it even when I’m not getting great feedback from the world. It was sort of embarrassing because my family, all my parents’ friends, and all of my friends knew I was writing a novel. My frenemy-type friends even knew I was writing it. So it was tough to say that I sent it to agents and it’s not going to get published; it was a defeat. But to know I could survive that, and if I’m serious about it then I just have to keep going even without that kind of encouragement from the wider world.

It’s definitely intimidating in a strange way. It’s been about two years since the novel was forcibly taken out of my hands when my editor was like, "You cannot make any more changes." I’m really obsessive and I would have continued to want to call her in the middle of the night and say “we have to add a comma to page 39!” And in the few months before the book came out, and even a year after I was quite busy with other stuff both relating to the publicity and marketing along with some journalism assignments that I was encouraged to do because it’s just good to get you out there when your novel comes out. But then in the past six months I definitely started to feel like I missed writing fiction. I’m lonely, I can’t wait to start another.

SEE ALSO: Matt Sumell Q&A: Novel Talks At Neon Tommy

You speak frequently about your appreciation for 18th and 19th century novels, many of which have less than likable characters. Yet you note in an interview with the Weekly Standard that “we live in a moment that prizes egalitarianism so much that as readers we often expect to be flattered—we don’t want to feel threatened or implicated by a character’s intelligence.” Why do you think we have this desire for characters to flatter us? Where has this come from in our literary culture?

I think that this is sort of commercially driven, that there is a desire for characters that will appeal to the most readers. And a lot of books (and TV shows) are set in this sort of mythical middle class world where people don’t talk about where they went to college, and everybody seems to have enough money but they aren’t rich. This middle world which I think is very comfortable in a certain way. But I felt that it wasn’t true to my experience.

I wanted to write about someone like Nate who is very specific. His judgements are snobbish and he’s very aware of having gone to Harvard (and makes other people aware of that too). That felt true to a lot of people who I knew, but the world of the book is so rarefied and self-consciously intellectual that I worried it would rub a lot of readers wrong. And I think it did, and I think that’s fair. I stand by my decision that this is a valid world to write about. It’s alright to write about a more specific milieu. But I get why people think that all of these characters are snobbish, that they all drop too many literary references, that they are too proud about where they went to school. I sympathize with that.

In the same Weekly Standard interview, you address a topic that has grown increasingly prevalent, especially on college campuses. You explain that “Sexual liberation has tended to mean that typically male behavior is held up as the norm and seen as something women should aspire to. By which I mean, I think young women often feel they should be okay with casual sex—that it’s a sign of an adventurous spirit—or that they shouldn’t be so focused on relationships and worry that to be concerned with relationships signals a failure of intellectual or artistic spirit. To me, the reverse is true. Men like Nate should care about relationships more.” Many girls on college campuses have taken this first definition of sexual liberation to heart, and in part contributing to the hook-up culture. Is that something that concerns you? Do you worry that it will only produce more Nate’s in the world?

I’m my boring 38-year-old married self so I can’t speak to that as much. But I’m so glad you brought that up because I do stand behind it. I feel like it’s a very tricky territory, because I don’t want to imply that women never or usually don’t like casual sex. I don’t even want to pretend to speak for people other than myself or my close friends. But I do believe that it’s an okay thing, a valid thing, to want a relationship. I think that there’s a way in our culture that we’re conditioned to see that as a little bit weak or needy. Just somehow not as admirable in a creative or intellectual sense. And I don’t think those things have to be incompatible.

And I do stand by my critique of Nate in that his problem is that he doesn’t think about relationships enough. It’s a problem because you experience moral, intellectual, and even artistic growth in dealing with close romantic relationships with other people to a degree that Nate doesn’t experience in the book. You get invested enough to really see things from the other person’s point of view, and that is actually really important in terms of being a writer.

So I'd like to see that paradigm be widened a little to where caring about relationships doesn’t mean you’re an empty headed person who just has no ambitions or interests. You don’t want to be pegged as this needy girl who thinks about boys all the time. It’s not an attractive stereotype. That sense of a dichotomy of being completely independent or completely needy and pathetic hurts all of us. There might be this middle ground that we should all, male and female, aspire to.

SEE ALSO: Creating Diversity in Creative Writing, One Student At A Time

With Nate, you chose to write in close third person. Did you find that easier than writing in first? Or was there a narrative motivation for writing in third?

I think a narrative motivation. There’s something about the close third person that I really like because it gives you the ability to hear a character’s thoughts very closely, but as the author you get to inflict them a little bit with your point of view. If Nate were writing the book, or thinking in the first person, his tone would be more ingratiated in a way that when he speaks to other characters he tries to be charming and he wants to be likeable. But I felt like by giving his thoughts without his consent (not like he’s a real person whose privacy could be violated) you don’t get that spin. So when I talk about things that were really important for me to talk about, like certain thoughts he has about women’s appearances or women’s bodies, there’s a way in which you’re both getting his thoughts but I hope some of the narrator’s implicit criticism as well.

You reference this a bit in your interview with GQ, but were you concerned before the novel’s release that it would be considered “chick lit”, and was that something that seeped into your mind during the process of writing? Were you consciously attempting to subvert that assumption?

I was conscious of it, definitely, and on the one hand I had this deep feeling that this book wasn’t chick lit. That books about dating or courtship aren’t any less serious or valuable than other books, and in part so related to my love of Austen. Courtship, or dating as we now call it, was considered such a valid subject for 19th century novels. It’s unfortunate that it has changed, as it is such an important part of how we live in our twenties.

That said, as a woman writing about these topics I definitely worried about being pigeonholed. From the publisher’s perspective, there are a lot of incentives to packaging a book as “chick-lit” or women’s fiction because women make up the bulk of novel readers. So I was very lucky that my editor saw it the way I did and thought it was important to have a cover and a jacket copy that was gender neutral. And I should clarify, I don’t in any way mean to imply that I think there is anything wrong with books written with a female audience in mind, I just wanted this book in particular to be read by men who would think about it.

I feel very fortunate in how the book was received. But I should say that I have no idea how the book would have been received if it were very similar but about a female character. I think in some ways I got lucky because I found this loophole where you can write about dating and be a woman but you put a male character in the center. But obviously a woman shouldn’t have to write about a male character to be taken seriously.

One of the things that stood out so much about "The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P." is that it is a serious book about dating. Why do you think that topic is not taken seriously in literature even though it is a common source of emotional turmoil?

I think it’s a big topic, and I’m worried I could take a whole hour talking about it, because I think to a degree it’s a gender problem. A male writes about the topic and, if he does it well enough, it is seen as literature. Whereas the bar is higher for women to elevate writing about relationships beyond that chick-lit category. And I think that there’s a way in which women, if you want to be taken seriously as a literary writer, might respond to this by separating themselves from writers who are seen as chick-lit writers and by avoiding the topic entirely. I think that some women writers are a little nervous about writing about dating. Even the word dating. Before the book came out (now I’m more relaxed about it) I would try to avoid the word dating and say it was a book about relationships. You say the word dating and people picture pink high-heeled shoes on the cover. And it’s stupid because we all date, male, female, gay, straight, it’s a big part of all of our lives, but that word brings the connotation.

Check back to Novel Talks with Neon Tommy for our second portion of this Q&A with Adelle Waldman regarding literary education.

Contact Staff Writer Madeleine Remi here. Follow her on Twitter here