Raising The Minimum Wage Won't Sink L.A. Businesses

Kaplan worked at his father’s market, managing the deli counter while his dad ran the butcher shop. After his father retired, Kaplan and his wife converted the store into a restaurant. “We always kept the name [Hugo’s] because my father was a wonderful man.”

The first Hugo’s Restaurant opened in the early 1980’s in West Hollywood. In 2000 the Kaplans took on additional partners and opened their second restaurant in Studio City. Five years later they opened the first Hugo’s Tacos nearby, with the second following in 2008. “I can’t remember exactly, but we opened either a week before or a week after the economy crashed in 2008. We had a rough couple of years there.”

Kaplan and his partners eventually opened a third restaurant and taco stand during the Great Recession. They not only expanded, but did so without firing a single employee. “We are committed to preserving all of our jobs. We actually created about 70 jobs … probably more than IBM,” Kaplan chuckles.

Now, as the economy is recovering, he’s girding the added costs he’ll be stuck with as the minimum wage rises. Even though he pays over the current $9 an hour, as that rises, he’ll be forced to keep pace.

SEE ALSO: The Hidden Costs of Raising the Wage

At Hugo’s, labor costs account for 30 to 35 percent of their total expenses. Kaplan thinks he might have to raise prices 25 to 50 cents per item, amounting to an 8 percent price increase for his popular $2.75 tacos. “Restaurants are a very tough business,” he says, adding, “We have a low ticket average, high employee count and a perishable product. I think a lot of small businesses are afraid that they’ll lose their customers if they have to bump their prices up, but we are confident in our product.”

He thinks increasing the minimum wage to $13.25 might harm new businesses. “The first couple of years’ profits are never what you want them to be because it takes time to get your staff right and figure out other details.”

The qualities that helped Hugo’s survive the recession are the same ones that could help it adapt to an increased minimum wage. Customer service remains a priority. His employees strive to give every customer the “gift of service,” which means being present, kind and respectful to coworkers and customers, even rude ones.

Hugo’s values customer loyalty, and that’s also one reason why he pays above minimum. Kaplan sees some of their regulars five or six times a week. He believes their patronage helped him grow the business during the recession.

Kaplan acknowledges that the success of his first three locations bankrolled the last three during the recession. “I probably would have failed had we opened new businesses without our established locations to fall back on.”

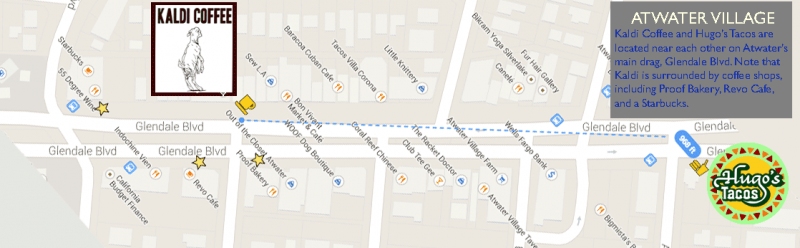

Of course, not every business in the restaurant industry can rely on such a steady clientele. Kaldi Coffee is a small, independently operated business with four locations, all of them fairly close to one another. It, too, is now looking for ways to absorb increased labor costs if the minimum wage goes up. That will likely mean raising prices.

Kaldi’s general manager and roaster, Ivo Ivankovich, has held many minimum wage jobs and advocates a minimum wage increase. Ivankovich’s first minimum wage job paid him $4.65 an hour when he was 16. Since then he’s worked jobs that span ditch digging to photocopying. Working at Kaldi for six and a half years, he makes a couple dollars an hour above the $9 an hour minimum wage.

But his coworker, Steve Zorbalas, makes the minimum wage working as a barista at Kaldi—more than he did applying his four-year political science degree to tutoring and other academic jobs. Zorbalas earns $40-$60 in tips for a five to eight hour shift. “I do okay after tips,” he says, but noted that the financial realities of living in Los Angeles, where rents are high, can be overwhelming.

SEE ALSO: The Low Wage Worker Who Doesn't Want a Raise

When it comes to working for minimum wage, Ivankovich and Zorbalas both agree that employers need to understand what it means to work for minimum wage. “It gets a little frustrating when [your boss] wants you to devote yourself to his dreams for minimum wage,” Zorbalas says. At a previous minimum-wage gig, he recalls, “I never saw so many people quit on the job. Like literally take their aprons off, crumple them up, throw them in the corner and never come back.” Ivankovich believes minimum wage is arbitrary and workers should earn a fair wage based on what they believe their time is worth. Both Kaldi employees see their low-wage jobs as a means to an end.

Labor is not a major cost for Kaldi’s, so while prices might rise slightly to compensate for increased wages, they don’t think it would deter their regulars. Raising prices “would certainly affect our tips,” said Zorbalas, but this trend is usually temporary.

The Critics

Many businesses aren’t as ready to roll with the changes as Kaldi’s and Hugo’s might be. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce argues that the increase will cut jobs and employee hours. Chamber President Gary Toebben said it would cause businesses to “move across the street to cities that were paying lower wages.”

Kaldi and Hugo’s are located in Atwater, near the city line with Glendale, but neither business expressed concerns about moving. Losing regulars because of a move might be more harmful than paying higher wages.

Another business lobbying group, the Central City Association, believes Garcetti should spread the increase over a longer time period. Increasing the wage more gradually could allow businesses to make small incremental price changes, thus retaining customers while maintaining revenue.

Around L.A.

L.A. is not the only city discussing a minimum wage increase. Santa Monica and West Hollywood’s city councils have begun preliminary steps toward an official analysis of the minimum wage. Culver City and Pasadena’s mayors both acknowledge that increasing the minimal wage might help some families.

SEE ALSO: A Few Dollars, A Big Difference

Whether or not these cities will seriously consider making a change remains to be seen. Many minimum wage employees who work in these wealthier areas commute from more affordable parts of Los Angeles, which removes a significant political motivation for councilmembers. The people who would benefit from an increased wage in their areas are not part of their electorate, and those that are would likely only stand to lose from such a change.

Arguments that raising the minimum wage will destroy businesses took a hit after Seattle and San Francisco increased their respective minimum wages to $15. Atwater is not a perfect microcosm of the city, given its artsier vibe and relative lack of industry. But at $53,872, the median household income is a smidge above Los Angeles’ $49,745.

This story is part of a minimum wage series produced by USC Annenberg students.

Contact Contributor Allie Farinacci here.