In California, A Fight For Public Education

The 21-year-old University of California, Berkeley senior is part of a growing student movement fighting tuition increases in the 10-campus system.

Gomez, and 12 others, was arrested Nov. 17 when they attempted to block the entrances to the UC Regents meeting at the University of California, San Francisco. Many congregated in a parking garage leading into the conference center, hoping to enter the meeting. When police kept them from entering the meeting room, they blockaded the area and tried to keep out the regents themselves. The regents approved an 8 percent fee hike, raising annual tuition from $10,302 to $11,124.

Gomez, who serves as external affairs vice president of the student body, said he was pepper sprayed, beaten and suffered a concussion from being hit in the head with an officer’s baton.

“I saw people getting trampled. I saw my friend getting a baton smashed into her neck,” he said. “It has become clear that the UC regents don't want the public to be at the public meetings. They will use as much police force as possible.”

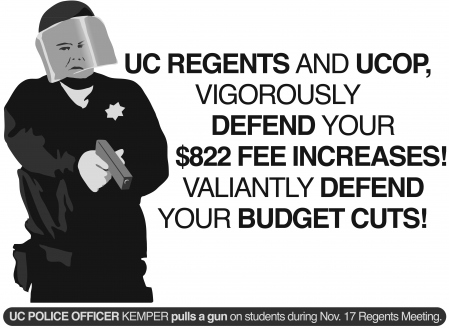

The image and video of an officer who pulled his gun on the crowd of about 300 is now being circulated to drum up support for the movement.

The UC police chief defended the officer who pulled his gun, and Peter King, director of media relations for the UC Office of the President, said it was self-defense.

An open letter from the Council of UC Faculty Associations asks King to explain the “source of the details” in his statement exonerating police actions during the protest, citing it as a “matter of public concern to know how your statement came about” and requesting an investigation.

Gomez was charged with obstructing a police officer in the line of duty and released two hours later.

But being arrested did not deter him—he took part in a protest march on Friday.

When word got around of Wednesday’s protests and the police brutality, it inspired others to come out to protest last Friday.

“I think when you're determined to make your voice heard, it's not a terror that's going to demobilize you,” he said.

Members of the University of California Police Department are also reportedly making home visits to those they know or assume were involved in Wednesday’s protest.

Officers showed up to Gomez’s building and asked his building manager to speak with the student. Gomez refused. They then told him they wanted to talk about Wednesday’s protest in general and not his specific case, but Gomez again declined.

“If they wanted to use their resources they should be investigating why that officer pulled a gun on students,” he said. “You don’t just pull out your gun as a precautionary measure to scare somebody into complying with you.”

This is not the first time university police officers have taken a hard line on campus protests, said Nick Palmquist, who graduated from Berkeley last spring.

Gomez said the police stood out at many organizing events this year and last year.

“The UC administration has made it clear that they're going to intimidate and silence the people who are involved whenever they take action,” he said.

It was at an earlier protest, in the fall of 2009, that Gomez was arrested for the first time.

The protestors are seeking to draw attention to the effects of tight budgets on their education.

Walk into any overcrowded classroom, speak with any laid off teacher or help students pay for their education after a tuition hike--the effects of recent cuts in higher education nationwide are painfully apparent.

UC students are not new to protesting. They hit the streets last November when the regents voted to increase undergraduate fees by 32 percent.

And though state funding for the system has increased to $370 million this year, it’s not enough to make up for the budget shortfall, which had led to the recent changes.

Campuses across the country, including the UC system, participated in the Oct. 7 National Day of Action, which saw rallies, teach-ins and sit-ins.

The actions mirrored March 4, 2010, when tens of thousands of students, parents, teachers and workers across the country protested budget cuts on California's designated “Student Day of Action.”

Palmquist, who now lives in Oakland and follow the protests, said last year’s students hadn’t quite found their footing. Though this year’s actions have been more spontaneous, he said the organization seems much improved.

But organizing undergraduates on campus remains a challenge, he said.

“There is a sizable portion of people who understand the UC regents are not their friend, but there's this residual belief that this is mostly a state problem and a problem of state funding,” Gomez said.

Though the recent protests have drawn national media attention, Palmquist said the undergraduates are divided in what they want to fight for, making it more difficult to organize as a whole.

Gomez agreed that the protests have differed this year as students, faculty and staff have split into factions, some fighting a change to the Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan, some fighting for the DREAM act, others fighting tuition hikes.

While some might say student apathy is the problem, Gomez disagrees, noting that it’s the “myth of apathy” that’s the problem.

“I think that the people involved in any protest movement are a minority. The people who are actively involved are always the minority,” he said. “But it doesn’t mean we’re not supported by a large number of students, and I think we’re with the majority when we fight for public education.”

No official leader has emerged to take control of the movement, which is coordinated through social media like Facebook, Twitter, blogs and e-mail, Gomez said.

“There’s this idea that the way you measure a movement is by how many people show up to a meeting. But it’s these acts of repression that are keeping the students who were active last year from participating this year….We can’t have meetings without the police there, can’t have active organizers without being told, as in one case, that they’re being watched by the police,” he said. “These things have had a chilling effect on some, but I think there’s a majority of students who are with the cause.”

Meantime, students are working to mobilize for next semester.

“Protests work and protests need to continue,” Gomez said. “There is one struggle that all these things are connected to and that's education…The education movement isn't just about UCs.”

To reach editor-in-chief Callie Schweitzer, click here.

To follow her on Twitter: @cschweitz

Sign up for Neon Tommy's weekly e-mail newsletter.