Left For Dead

More than 1,500 corpses on the unclaimed persons list have not been collected due to economic hardship. Countless more names are trapped on the list by protocol. (photo by Kim Daniels)

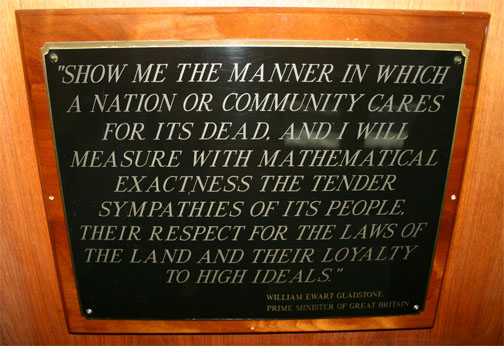

On the wall of building 1102 at the Los Angeles County Coroner's Office on Mission Road hangs a modest black plaque tucked in the corner of a Spartan lobby. Its words come from four-time British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone: "Show me the manner in which a nation or community cares for its dead and I will measure with mathematical exactness the tender sympathies of its people, their respect for the laws of the land and their loyalties to high ideals."

There are 4,705 unclaimed bodies on file with the L.A. office; Names that wait in limbo for loved ones to arrive and lay them to rest. Some of them are the city's homeless; some of them are immigrants with families too far away to come and collect them; some of them died without a name or an age, a hair color or a height being recorded - too decomposed or disfigured even to tell what color their eyes once were. In 2008 alone, 1,074 decedents were added to the city's file.

The numbers seem to reveal that L.A has an astonishing collection of unwanted and forgotten residents. But detectives at the Coroner's office claim to have located kin for the majority of cases. So why does the total number of listed unclaimed rarely change? Despite a 75 percent success rate, according to the detectives responsible for locating loved ones, the number of unclaimed bodies on file rarely fluctuates by more than five names in a three-month period. From October to December 2008, four people were added to the list.

According to the coroner's office, the discrepancy is being caused by red tape and a shrinking economy. Some people on the unclaimed persons list, for instance, have long been cremated by the county and buried in a mass grave at the Evergreen Cemetery on 1st Street in Boyle Heights, leaving nothing to claim even for those that might feel compelled to do so. In many cases, decedents on the list are neither unwanted nor forgotten, but condemned by the price tag their bodies now carry. According to the county coroner's office, hard economic times are robbing Angelenos of the ability to claim their dead.

Funeral fees can add up to thousands of dollars," said Lt. David Smith, one of two county investigators in charge of locating next of kin for the unclaimed deceased. "It's a big financial hardship on families."

Instead, many families are forced to put cremation rights into the hands of the county. Once the body has been cremated, kin can claim the ashes by paying $550 plus the cost of transportation and holding. Or, as Smith pointed out, they can leave the ashes with the county and wait for them to be buried in a mass grave for free.

Under the health and safety code it a misdemeanor to not perform the duty of internment for a person if you're capable of doing so," said Smith. "But if you've got no money, you've got no money."

The number of families unable to bury their loved ones or even collect their ashes has risen during the economic crisis, Smith said. More than 1,500 bodies have not been claimed for this reason to date, and officers have witnessed an increase in the number of families suffering this plight in the last two years. Welfare options are limited. Los Angeles County only offers one choice for family members who cannot afford cremation or funeral fees, and that is to start saving.

The county offers a disposition program where we'll cremate the person and hold onto the cremains for two years to give the family the time to come up with the money," Smith explained. "If at the end of the two years they haven't done so, then the ashes are buried in one common grave."

In addition to the tough economic climate, outdated technology and complicated clerical procedures in the coroner's office are making hard work of reducing the number of unclaimed bodies in the system. In theory, searching for kin has become an easier process. "As time has gone on we've had better luck because computer databases have gotten better," said Smith. "Information has become more readily available." But recent technological glitches have actually pulled progress backwards at the coroner's office.

In November 2008, the office was alerted to an error in the database when a member of the public spotted an unclaimed person listed with a death date of 2011. A number of similar anomalies could be found scattered throughout and it was discovered that the database had recently crashed, and much of the data had been lost. According to Smith, Birth and death dates were replaced with "January 01, 1900" and key identifying characteristics of decedents, such as height, disappeared.

The database is solely web-based, which is a cheap but volatile way of storing important public information. It can also mean a complicated process of inputting, editing and navigating that information. The list, available to the public online through the county coroner's office, is not searchable by any terms other than a specific case number. Instead, users are required to click through 4,680 names 10 at a time. The office is currently in the process of reassembling the lost data, said Smith, but holes still appear in many of the fields.

If the economy and flawed record-keeping aren't the culprits for the impenetrable length of the unclaimed persons list, then red tape and inter-department communication might be. When an unclaimed body is brought to the coroner's office, it is held for 30 days while an investigation is launched to locate family, Smith said. The deceased person is listed in the county's database as "unclaimed" and, if no one steps forward to claim him or her, the body is sent to the morgue.

But even if the body is eventually collected, only specific members of kin can warrant a name deletion. In some cases, this means that names on the unclaimed persons list will remain there indefinitely regardless of whether or not they have been laid to rest.

Take the case of Edward Joe Adams - "E.J." to his friends. Adams was walking down the sidewalk on 65th Street near Hyde Park in June of 2008 when a man approached and shot him with a 9mm handgun. His body was collected by the coroner's office, which is obligated to take charge of all suspicious, unlawful or unnatural deaths, and "Edward Joe Adams" was added to the unclaimed persons list. Meanwhile, a makeshift memorial shrine was put together at the spot where Adams fell, pieces of cardboard tied to the fence with dedications scrawled upon them and flowers placed on the sidewalk below.

E.J. will be missed," read a comment by Robin Russell on the Los Angeles Times' Homicide Report blog entry on Adams. "We grew up with [him] and he was like a cousin to me and my brothers."

With friends around to build shrines and write words of condolence, Adams did not seem a likely name to join the list of unclaimed. He had a large family and a girlfriend. Would none of these individuals step forward and accept his body?

Adams always used to talk about the son he had straight after high school, said P.E. Russell, who claims to have been "like an uncle" to Adams, as well as the best friend of Adams's father. But Adams had not stayed in touch with the child or the mother. His son, Russell said, would now be around 25 years old. Given the way the coroner's office tiers next of kin -- spouse first, then children, then parents -- an investigation was launched to find this long-lost son immediately following Adams's death. When that search ran its course after the 30-day cut-off and no "son" could be found, the coroner's office released the body to the morgue, where it was soon claimed by one of Adams's Los Angeles-based cousins.

A funeral service was held on August 16," said Robin Russell, P.E. Russell's son who worked with Adams from time to time at P.E. Russell and Sons Roofing in Huntington Park. "We found out about E.J.'s death immediately, but it took a month and a half for the coroner's office to look for his children. They would not release the body until then."

According to P.E. Russell, Adams was living with girlfriend Gloria Miles at the time of his death. Although family members claimed the body, Miles arranged the funeral with the help of money received from the Crime Victims Fund, a 24-year-old federal program for things such as medical costs, mental health counseling, lost wages and, indeed, funeral and burial costs.

Someone else claimed his body, and I arranged the funeral," said Miles. "We had a small memorial service for him."

But despite diligence on the part of the coroner's office and the fact that Adams's ashes have been put to rest by his family, his name still pops up on page two of the county's database. And there it will remain, forever, or until his long-lost children come forward. Adams is just another name without a body on L.A.'s long list of "unclaimed" dead.