Hooked Anew: The Rising Heroin Epidemic

The San Diego Association of Governments’ Criminal Justice Research Division (SANDAG), a planning and policy-making organization, found in 2012 that opiate use was at an all-time high for young adults ages 18-24. This demographic was more likely to test positive for opiates than older adults.

“Without a doubt, it’s becoming a huge problem. There is a huge heroin epidemic within our youth and it’s not only in San Diego. It’s growing nationwide,” a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent said who asked to remain anonymous for job security.

ALSO READ: Neon Tommy's Full Coverage Of Drug Policy

For the Brown family of Carlsbad, Calif. their worst nightmare became a reality when their only son passed away from a heroin overdose in Sept. 2013. Only 21-years-old, Ian Brown was undergoing his fourth round of rehabilitation treatment and holding down a full-time job when he went to his car on a lunch break to get high one last time. The coroner’s report cited a relatively “small” amount of heroin in Ian’s system, noting that because he had been clean for nearly four months, his body failed to tolerate exposure to the drug.

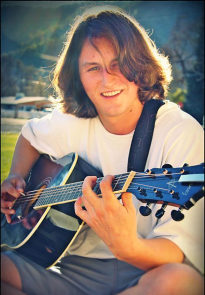

“Ian himself was athletically gifted…in fact a top ranked juniors tennis player in Southern California. He also loved to skate, surf and play guitar. He had a kind, easy-going personality that attracted many people to him. He was a great kid,” Ian’s mother, Cathie Brown said.

According to Brown’s 19-year-old sister, Courtney, Brown first tried heroin in the 10th-grade on a ski and snowboarding trip hosted by SWAT, an extremely popular weekend getaway for high school students in the north San Diego county area that is notorious for extreme partying with little to no supervision.

“This was the reason straight from his mouth: ‘I didn't think it was much of a big deal since you just smoked it.’ After all, he had smoked weed and cigarettes and didn't think of it as a huge jump,” Brown’s mother said.

This notion that heroin is seemingly not any “worse” than recreational drugs like marijuana, a drug that runs rampant throughout north San Diego County with little repercussion from law enforcement, could be the reason that young adults try heroin even once. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), heroin is made from morphine, a natural substance obtained from opium poppy plants. First manufactured in 1898 by a German pharmaceutical company, it was marketed as a treatment for tuberculosis and morphine addiction. As most substitute drug treatments are though, heroin soon became more addictive than the morphine it was supposedly protecting against.

“When everything really clicked for me was sophomore year. I remember sitting in 'the green machine’ [Ford Explorer] racking lines of coke itching to get our fix. We all looked over the shoulder of the person racking the lines as we drooled. In that car my friend looked at me and said, ‘I never thought we would be drug addicts.’ The thought never came to mind until that moment. That is when it all came real,” a 21-year-old close friend to Brown said who asked to remain anonymous for job security.

ALSO READ: McDonalds's Drive-Thru Employee Under Investigation for Dealing Heroin

Once a spontaneous and charismatic teenager, Brown’s family and friends started to notice that he was beginning to change—no longer the young man they once knew, heroin began to control Brown’s every waking moment.

“That same year [during 10th-grade] Ian started to become something, someone else… Ian started developing multiple personalities, He would act and talk like someone from a completely different life,” the close friend to Brown said.

“Our son had totally changed and slipped away from us. He didn't partake in any of the activities that he had formerly loved and was physically a wreck compared to the healthy, strong young man he had always been,” Brown’s mother said.

“I would walk into his room and see him passed out late at night and have to check his pulse to see if he was still even alive. I would see needles and tin foil and horrible things. I would watch him close the bathroom door, turn the shower on and stay in there for 45 minutes. I knew exactly what he was doing…heroin,” Brown’s sister said.

After admitting to his family that he was struggling with drug abuse, Ian spent the next three years in and out of four rehabilitation treatment centers, trying Suboxone, Subutex and Methadone treatments, medications that work to reduce the symptoms of opiate dependence.

Despite a committed attempt to become permanently sober, Brown could not shake the high that heroin was granting him.

“It’s just you and the drug and nothing else matters. No matter how much you want to care we just weren't capable of it. Ian and I would talk about the damage we were doing to our loved ones and we knew how selfish we were being and how much we wanted to stop, but it’s just a vicious cycle,” Carter Adams said, a close friend to Brown and former heroin user.

For many heroin addicts, the attempt to get clean through formal rehabilitation is restricted by a constant return to the same environment where the drug abuse originally

flourished. Although progress may be made within treatment centers, when faced with the same type of people and surroundings that once fed the addiction, it becomes almost impossible to resume the lifestyle one had prior to the addiction.

“When one uses drugs regularly, one becomes an expert in drug use…acquisition skills, knowledge on how to use, language of the drug being used. Quitting does not give someone an automatic replacement for the lifestyle in which one have become proficient,” Steve Sussman said, a professor of preventative medicine and psychology at the University of Southern California.

“Living in San Diego can certainly affect your inability to get clean especially when your drug of choice is primarily distributed from Mexico and being 30 minutes from the border definitely doesn't help the situation. If you go to Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous or any anonymous program you're going to hear people say, ‘change your playground, playmates and playthings,” which basically means you have to change everything. In my case I had to move to San Jose and completely start fresh,” Adams said.

Heroin was the most common drug responsible for accidental overdose between 20 and 29-year-olds in San Diego and in north San Diego County alone there are an estimated 25,000 to 50,000 people that are opiate dependent, according to SANDAG.

When discussing what causes these young adults, who seem to have supportive families and affluent upbringings, to turn to drugs, many have pointed fingers at the normalization of prescription drugs in our society and the subsequent abuse within a generation that has been defined by pill abuse.

“This generation, up to 30 something’s, are the first generation that has had pharmaceutical ads on the television showing people taking drugs to alleviate problems. You see the depressed woman on TV: she takes a pill and then immediately goes outside to play with her children,” Rubin said.

It is possible that the same generation that has seen a rise in heroin abuse has also become desensitized to the negative implication of prescription drugs—only focusing on the quick fix these pills provide for any given problem.

A 2013 study by the San Diego Rx Abuse Task Force, a group created to address prescription drug abuse, found that nearly 20 percent of 11th-graders in San Diego County have experimented with prescription drugs.

In the SANDAG report that analyzed 2012’s drug abuse in San Diego County, 27 percent of the interviewees who ever tried heroin reported using prescription drugs before trying heroin and 63 percent of them said heroin became a substitute, solely because of increased availability and less expensive cost.

“These are educated, bright, achieving children who never ever knowingly choose to buy heroin. But they needed the high. And when the withdrawals would set in, it would take anything to suppress their withdrawals. From there kids just started skipping the pills and taking heroin because it became a normalized thing,” the DEA agent said.

ALSO READ: Flesh-Eating Drug Krokodil Found In U.S.

There also seems to be a sense of entitlement seen within first time drug users. Growing up in an environment where everything is handed to them on a silver platter, these young adults feel as if they are invincible—untouchable by the possibility that these drugs could do much more than just provide a euphoric rush.

“We started out as just young kids skating along El Camino Real smoking weed behind the movie theater. If you told any of us that we were going to be strung out within a few years, we would have told you that you were crazy,” Adams said.

“One of the factors that I think is going on in the community is that those kids feel protected. They’ve always been protected. And they rationalize that even if they do have a problem they have rehab to get cleaned up. I think they have an exaggerated confidence in their prosperity, in their youth and their families. That confidence facilitates them to experiment,” Heron said.

For 29-year-old Poway, Calif. resident Aaron Rubin, drug abuse may not have taken his life, but a night of partying in 2005 and an overdose on a mixture of prescription drugs and alcohol left him confined to a wheelchair, unable to speak or walk.

“We were an upper middle class family that was active in the community…Aaron was friends with everybody, was one of the leaders on campus and played defense as a football player all four years of high school. Never in a million years did I think this situation would become a reality,” Rubin’s mother, Sherrie, said.

According to his mother, Rubin was first introduced to prescription pills by a former football coach who would give muscle relaxers and Vicodin to players. Rubin’s mother never suspected suspicious activity or asked questions, but now stands firm by her belief that parents are actively turning a blind eye to their children’s drug abuse.

With the H.O.P.E. foundation, the Rubin family hopes to use their son’s survival story as a platform for drug abuse education. Partnering with law enforcement, the foundation travels to schools in the San Diego area raising awareness about the severity of heroin and prescription drug abuse.

“There are a lot of pieces to the puzzle. The most effective use of our time right now is to participate in education. Primarily talking to the young adults that are going to

make that choice. It’s about empowering the young adults that are going to make that decision and help them see the consequences,” Rubin’s mother said.

ALSO READ: Governor's Penny-Pinching Could Put Heroin Addicts Back On Streets

The Brown family also hopes to utilize the power of education to combat drug abuse with the Ian Brown Foundation, an organization that aims to give parents the necessary tools to educate their children and prevent future lives from being taken too soon.

“Ironically—Ian and I had always discussed how, when he got well, that he could go to schools and talk to other kids about the horrors of a heroin addiction. Ian never got the chance, so I am hoping to impart that message for him,” Brown’s mother said.

“To me, Ian was invincible and so strong. I thought nothing bad could ever happen to him. Ian was the strongest person I have ever known and he still couldn't beat heroin,” Brown’s sister said.

Behind the seemingly quaint residential neighborhoods in north San Diego County lurks a deeply rooted issue that is triggering young people in San Diego County to turn to drugs as an escape—an escape that is ripping families apart at the seems and taking vital components of our society’s future down with them.

Reach Staff Reporter McKenna Aiello here, and follow her on Twitter @McKennaAiello.