There's No Substitute For Creativity In The Classroom

The group reviews the lesson plans they learned in the previous session.

(photo by Jean Luc Renault)

Mary Ann Tate sits across from me at a lunch table in the breezy, plant-filled courtyard inside Inner-City Arts. I'm eating a homemade peanut butter and jelly sandwich, nearly oblivious to the fact that Skid Row is a stone's throw over the center's immaculate walls that gleam in the sharp noontime sun.

The first-grade teacher tells me about her students at 9th Street Elementary School a few blocks from here.

"Some of them are living in boxes," says Tate, who moved here from the Philippines in 1989. "I have a lot of transient students. One came and went in two days."

Tate says many of the students' parents are drug users, that is, if they have parents at all. The kids have different priorities than the middle-class students she used to teach in Silver Lake, she says.

"You see kids saving an apple or some crackers from school in their bags for later," says Tate, who will sometimes bring in cupcakes to reward her students. "Food is a big motivator, the students are so poor."

Tate is one of about 16 others--mostly teachers--paying $150 to attend the Annenberg Professional Development Program's "Creativity in the Classroom" series. It's held at the non-profit arts center, which normally hosts Los Angeles-area students of all ages during school hours in its top-of-the-line facilities. These include a ceramics building, a black-box theatre, a cavernous music studio and a dance floor so sumptuous you cringe at the thought of putting your socks and shoes back on after a two-hour practice session.

Director of Professional Development Jan Hirsch runs the 35-hour seminars, acting as an engaged host and emcee as the attendees move between lessons and instructors. Teachers can use the seminars, held for seven hours on Saturdays spanning the semester, toward points that will help them get a raise. But that seems like an afterthought during today's program, the group's third of five. They'll use the lessons learned here in their own schools--many of them L.A. Unified--that can't fund arts programs.

But are these projects practical to students like Tate's who barely eat outside of school? Today we've learned how to sculpt ceramic masks, use songs in lesson plans and incorporate interpretive dance techniques into the classroom.

Which is exactly why the "Creativity in the Classroom" series is like a fresh piece of fruit for students who have been force-fed the gruel of authoritarian education their entire lives.

Tate tells me about what her students thought of a paper-sculpture exercise she picked up at a previous session. "They love it. Even my high-maintenance kids focus on the work we do," she says.

Inner-City Arts has a strict code of "validating the creative impulse." That's number one on the center's list of "Seven Big Ideas." No wrong answers, no criticizing the final product--only learning as much as possible about why someone created something or why someone likes or dislikes a painting or a dance move.

But number three's equally important: "It's all about the connections."

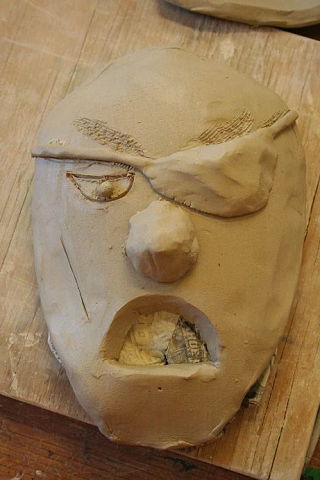

That's obvious today. As I put the finishing touches on my clay pirate mask, smock-sporting teachers crafting their own characters agree there are many lessons molded into the activity. The little ones will love cutting out shapes. Making sure there are no air pockets in the masks that will explode when fired in a kiln is a quick lesson for students old enough to grasp physics. Plus, it's fun. Everyone groans when clean-up time comes.

Rhythm, tempo, pitch, syllables, counting, languages--the list goes on to how many applications the seminar's participants find in our singing lessons as we clap along to a xylophone song about friends and sunshine.

Dancing's no exception. Sure, most of us look like stiff-limbed goons, but it takes teamwork, trust, problem solving and even sweat to execute our moves without clacking skulls or dropping one another during a counterbalance exercise.

Shortly after Tate tells me about her students, she's speaking with other teachers about growing gardens in schools to help build healthy diets and how some critics call the idea elitist.

"But that's one of the most basic things, farming," says another teacher at our table.

What are the arts except a fresh garden from which to pick healthy morsels that make life taste better? Why deny children their rightful urge to run, spin, play and get dirty, all while learning?

We've spent the entire day doing just that, and I can see everyone is still hungry to learn more. If only the rest of the country could develop a taste for it, too.

My own masterful clay creation.

© Jean Luc Renault

Zainab Nigehbani flattens out clay she'll use to make a mask.

© Jean Luc Renault