'Available Light' in the Digital Age

When Lucinda Childs was choreographing “Available Light” around 32 years ago for the opening of MOCA’s Temporary Contemporary, (now the Geffen Contemporary), in Little Tokyo, she probably didn’t have modern computing in mind. But something of her trademark mathematical minimalism, reignited in a revival of the work at the Walt Disney Concert Hall this weekend, bears striking resemblance to what we might imagine as the inside of a computer’s brain—at least through this millennial’s eyes.

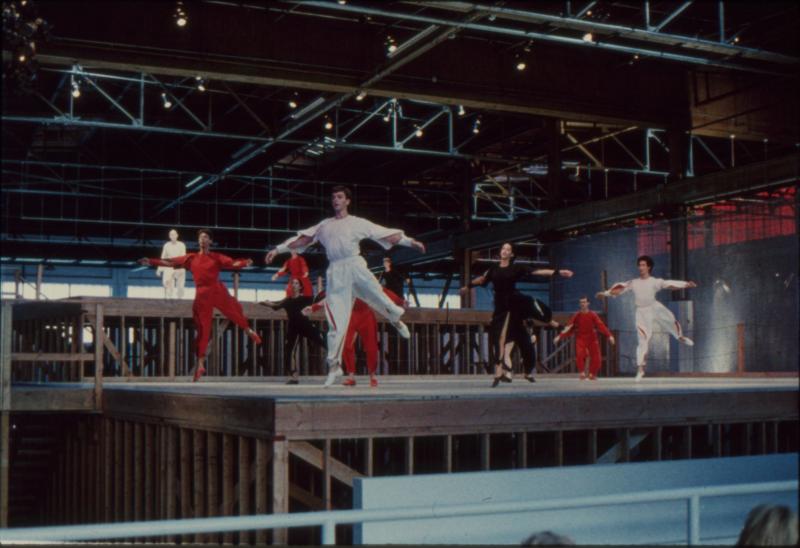

A landmark piece of L.A. performance art, “Available Light” combined the creative forces of three seminal postmodern influencers—Los Angeles-based architect Frank Gehry, San Francisco composer John Adams and New York choreographer Lucinda Childs—in a sophisticated synthesis of architecture, music and dance. Writing in 1983, MOCA’s Director at the time, Richard Koshalek, said the program, “will set forth many of the issues that the Museum, over the course of time, will continue to investigate.” Now in 2015, “Available Light” is still a puzzle to be decoded.

In the renewed rendition, every moving body acts with self-sufficiency, yet an unknown synchronicity binds them all. Like ones and zeroes, alternating on and off to communicate imperceptible bits of data, the dancers of Lucinda Childs’s company—eleven in all—activate and deactivate throughout the 50-minute long work. One springs into motion, hopping into a turning leap. Upon landing, another dancer picks up the phrase. The two spin like orbiting electrons in an atomic constellation of stock-still chess-pieces—performers standing at ready, waiting to be summoned into action.

As if by some magic keystroke command, one of the stilled dancers—without signal or sightlines for aid—jumps into the mix, while the first completely stops and waits to be called upon once again. It is subliminal communication at its most supernatural. The effect is even more mesmerizing when one takes into account the dancers atop the second level of Frank Gehry’s split-level set. One at a time, they hop, hover, spin and stir in perfect unison with the activated figures below, as if communicating by a million wi-fi pings.

Just as the ubiquitous “cloud” invisibly transmits photos, videos and documents from tablet, to desktop, to phone, a complex choreographic system underlies the dancers’ uncanny synchronization. But the clockwork ticking beneath remains unseen. The dance's techtonics patterns are almost predictable, yet not quite. Such obfuscation emits a vexing wish for explanation, yet also incites earnest intrigue.

John Adams’s pulsing and hypnotic deluge of tinkling electronic tones ("Light Over Water") indicates a metronomic impulse to support the dancers’ impeccably timed coherence, but its subversive shifts in tone and timing make it an unreliable guiding light.

The dancers themselves don’t give away many hints either. Aside from their color-coded status—skin-tight red, white or black sashes, rompers and shorts by costume designer Kasia Walicka Maimone—they move like anonymous automatons, executing Childs’s demanding choreography with stiff specificity. Eyes glazed over with concentration and bodies glistening in sweat, the dancers are slaves to Childs’s strict spatial architecture and obsessive variations on a few themes. But what is the human motivation (or mechanization), that drives them to tick on like veritable Coppélias?

Anna Kisselgoff provided a possible explanation in her 1983 review of the work’s New York premiere: “‘Available Light’ is a dance whose structural underpinnings are responsible for its ultimate beauties. The ideas behind it tell us something about the artists and our lives.”

While beautiful to behold the final result of "Available Light," the “ideas behind” the work operate more like an artful computer program. The aesthetically gorgeous design conceals an elegant, but also near-indecipherable code of labyrinthine loops and aggravated algorithms.

Bafflingly simple, yet infinitely complex, “Available Light” resists complete decryption, or as Susan Sontag wrote in her 1983 essay on Lucinda Childs’s choreographic style, “Its beauty is, first of all, an art of refusal.”

Indeed, “Available Light” extends few invitations. While sitting in the audience on Saturday night, I overheard two middle-aged patrons talk about missing the premiere of “Available Light” 32 years ago. When one inquired why they had not gone in the first place, the other replied, “We were very young. We probably wouldn’t have been allowed in.”

Ultimately, it is “Available Light’s” unwillingness to allow one in that gives the piece a lasting allure for veteran viewers and maddening appeal for the newly exposed.

In 2015, “Available Light” remains a mystery of time and space to the uninitiated, but I look forward to the moment when I can look upon the work again, perhaps another thirty years from now, with clearer eyes and a sense of history on my side.

"Available Light" ran at The Walt Disney Concert June 5 and 6, as a co-presentation of Glorya Kaufman Presents Dance at the Music Center, the LA Philharmonic and "Next on Grand: Contemporary Americans," a music and dance festival. For more information on future programming visit www.laphil.com/nextongrad or www.musiccenter.org.

Contact Contributor Christina Campodonico here.

For more Theatre & Dance coverage, click here.