Campus Safe Spaces Aren't 'Hiding' From Anything

Judith Shulevitz does not know my life, but she thinks she does.

Myself and others like me - college and university students who champion safe spaces on campus for students who have experienced identity-based harassment, violence or discrimination are the subject of Shulevitz’s criticism and disdain in a New York Times op-ed contribution published last Sunday called “In College and Hiding from Scary Ideas.”

Shulevitz advances the theory that certain hypersensitive students on campus are curtailing free speech in order to not be exposed to ideas that scare or offend them, which is ultimately detrimental to everyone’s learning environment.

“While keeping college-level discussions “safe” may feel good to the hypersensitive, it’s bad for them and for everyone else,” she writes.

She cites several examples of what she feels to be an intrusion of safe-space mentality into academic life, including: Smith College President Kathleen McCartney’s apology to students after a fellow panelist advocated for using the n-word in an academic context at an alumnae event in New York; the cancellation of an abortion debate at Christ Church College after students complained that both debaters would be men; and a Brown University Sexual Assault Task Force member’s decision to offer a recuperation space for students triggered during a debate on campus sexual assault.

None of these actions seem unreasonable to me. When student survivors of sexual violence experience trauma symptoms, I believe they should receive appropriate care. When a public debate is organized over whether or not a woman should have control over her own uterus, I can see why it’s important to include a speaker who actually has a uterus. And I don’t really think its a white person’s decision whether or not an anti-black slur should be explicitly used in the classroom.

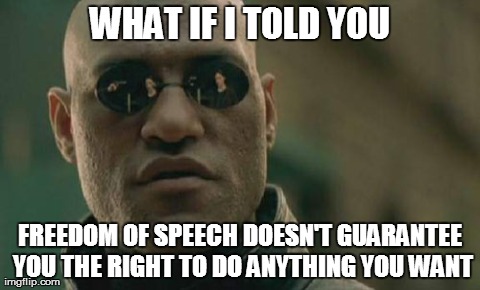

For Shulevitz, there’s no question of reasonability here because these actions constitute first and foremost an infringement upon free speech. It’s a clever appeal to a dearly held American value, a classic tactic that makes popular struggles against bigotry and dehumanization seem bigoted themselves. But her idea that justice for marginalized groups is somehow incompatible with our most fundamental right just doesn't stand up to scrutiny.

The First Amendment right to free speech reads as follows:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Put plainly, the freedom of speech ensures that you can’t be criminalized for what you say alone. Correspondingly, the state retains its obligation to protect you from violence, even if that violence is prompted by something that you’ve said. But it doesn’t protect against a person’s choice to respond to your free speech with their own. Free speech does not mean, “I can say what I want and the consequences will just disappear.” Free speech does not mean, “When I open my mouth, everyone has to listen to what I say.” Free speech does not mean, “My narrative is the only one that matters.”

If someone makes a racist comment, and someone else calls them out for it, that’s not stifling free speech - that is free speech. If students demand the cancellation of a talk they feel falsely represents their interests or experiences, they’re not violently preventing anyone from expressing their views. They’re simply choosing not to listen.

In fact, for students experiencing identity-based violence and discrimination, the choice of what and whom to listen to represents not only a right, but a strategic necessity. For centuries, public discourse in America has been dominated by an elite few, who have typically enjoyed the privileges of whiteness, masculinity, heterosexuality, wealth, physical ability or, most typically, all five. In fact, given that wealthy, straight, white and able-bodied men continue to comprise the (vast) majority of our state and national elected officials, a ratio often mirrored in the administrations and boards of our educational institutions, these individuals still dominate public discourse, even when that discourse concerns issues that most directly impact marginalized groups.

In this context, rejecting conventional narratives and embracing alternatives can serve as a tool for restoring equilibrium to an unequal playing field. Safe spaces restrict the access of traditional narratives, behaviors and paradigms so that alternatives can be advanced and entertained. They also provide a refuge from environments that are disrespectful or dismissive of trauma survivors which, while sometimes unavoidable, ultimately inhibit the intellectual and social progress higher education intends to foster.

This is especially important in light of the fact that traditional campus narratives have “safe spaces” of their own, and these spaces are as old as the colleges and universities themselves. Institutions of higher learning are filled with organizations where students spend money and personal accolades to affiliate with an in-group that shares their worldview, from the Greek system to honor societies to the university system as a whole, which continues to become less and less affordable for a larger and larger income bracket of Americans. What distinguishes these spaces from many of those cultivated by student activists is that they don’t share the objective of creating an alternative to, or reprieve from, a violent, oppressive or otherwise undesirable status quo. Rather, they exist to preserve existing social and intellectual traditions that are perceived as positive. Such traditionally-oriented spaces run the risk of being far more insular than safe spaces created for social justice purposes because their establishment is a confirmation, rather than an examination, of the already dominant discourse.

Shulevitiz’s piece overlooks the very intentional politics behind safe space creation, suggesting instead that the students who call for them must be “scared” of engaging with violent or oppressive ideas. But why would students who want to hide from scary ideas spend so much time and effort confronting those scary ideas and trying to deconstruct why it is that they’re scary? Why would students whose only interest is to shut out a particular viewpoint work so diligently to see that viewpoint change?

I am one of many students nationwide who is both a survivor of sexual violence and an advocate for violence prevention and response. I attend meetings with campus administrators and clinicians - sometimes multiple times per week, lead talks with law enforcement, conduct policy research and provide assistance to students seeking recourse or care in the aftermath of an assault. I do this while attending class, working a job and living my life like any other student. I also do this while managing my own experience of (rape) trauma and the inevitable wash of secondary trauma that comes with discoursing about sexual violence every single day.

To those of us survivor-advocates, who relate and relive our own experiences again and again in the hopes of preventing such acts in the future, the notion that we are “overprogrammed children” who “no longer experience the risks and challenges that breed maturity” is insulting, if not downright laughable. What is truly ironic is how Shulevitz’s argument works in the favor of the very sort of entitlement that makes today’s undergraduates “more puerile than their predecessors.” By belittling spaces that ask students, faculty and staff to consider the implications of their words and their actions, Shulevitz discourages self-awareness and taking responsibility for one's own behavior.

In insisting that students are “self-infantilizing” and “hiding from scary ideas,” Shulevitz seems be interested in making a case for the hard conversations. But the students fighting for safer campus spaces are the ones who are daring to have those hard conversations in the first place. If there is one nuance that Shulevitz fundamentally fails to grasp, it is that no space can be truly safe for everyone. To the contrary, it is the very spaces created to stand for and serve the safety and comfort of marginalized identities that incite the discomfort necessary for the rest of us to learn and grow.

It isn’t hard to pretend rape culture doesn’t exist; what is much harder is to acknowledge the role each and every one of us plays in maintaining an environment in which rape so frequently occurs with impunity.

It isn’t hard to stand in solidarity with the victims of the Charlie Hebdo massacre; what is much harder is to ask ourselves how our systems and institutions shape the environment in which such massacres occur.

It isn’t hard to read a passage from Huck Finn aloud and utter the n-word; what is much harder is to openly question why a white person is campaigning so vigorously for its academic use.

One letter to the editor, from University of Pittsburgh professor Kirk Savage, puts it well:

I don’t need to pronounce the n-word to have a productive discussion about racism. Obsessing over my right to hurt and offend seems especially myopic at a time when black men face far graver threats to their lives and security.

Indeed, Shulevitz has made a case for the right to offend, cleverly flexing her capacity to do so as she plays off racialized and gender-based violence as the spilled milk over which students should collectively stop crying.

But as Savage alludes to, it’s not offensiveness that students are worried about, but legitimate threats to their physical and psychological well-being. And yes, maintaining community well-being does matter in an academic setting - if you believe in the education system reaching its full potential, if you believe in cultivating healthy minds capable of critical thought, if you believe in equal opportunity and intellectual liberation and the same set of values from which we derived the concept of free speech in the first place. Undoubtedly, that’s why laws already exists to protect against disproportionate threats to student well-being in the education system.

It might have been a more prudent journalistic move for Shulevitz to refer to one of her own statements and ask herself, if “few of the students want stronger anti-hate speech codes,” what the hell it is that we might actually want instead. Undoubtedly, some students out there really do want to shut down dialogue and hide from frightening ideas - but I would venture a guess that there’s much more of that going on among folks who hold the same traditionally unchallenged viewpoints that student advocates are making so much noise about.

Especially since the students are, in fact, making noise. Shulevitz happens to know about all of these incidents - in which dialogue was supposedly stifled - because student dissent created a media conversation about them in the first place.

Huh. Maybe that was their goal all along.

Contact Senior Opinion Editor Francesca Bessey here; or follow her on Twitter.