The Replacement: A Kidney Story For National Kidney Month

Did you know that March is World Kidney Month, and that March 12th is World Kidney Day? Probably not. Why do we need a day for kidneys anyway? I went to a Los Angeles kidney support group to find out what it’s like to live with kidney disease, how big the problem is overall, and why they would like to hire Lindsay Lohan.

Hidden in Plain Sight

When I showed up at The Westside Kidney Support Group, no one in the room knew I was a doctor – yet. I don’t go out of my way to hide it, but when I’m in journalist mode, my purpose is to cover a public event or write a feature, not to do medicine. That day, I was there to learn what it’s like to live with kidney disease, a silent scourge in our nation. For two hours as I listed to their stories the tan and black business cards listing my MD rested quietly in my right pocket. My plan was to hand them out as the meeting concluded, just before I left.

I almost made it. As meeting was about to adjourn, a few group members lingered over trays of ham and cheese sandwiches on butter rolls and a raspberry trifle made from stacked sponge cake and cool whip. It wasn’t the best food for a group of people suffering from kidney disease, but this meeting was a celebration of sorts. In the last 30 years, severe kidney disease has been commuted from a death sentence, and a painful one, to a life on diet restriction, dialysis, or even a new life via transplant. Most of the people in that room — John Hegun, Laura Newsome, Linda Montyl and Lydia — were either losing kidney function or had lost it years earlier. Yet here they were, enjoying their butter rolls and swapping war stories about what it’s like to be short a couple of organs, and how frustrating it is that no one in America understands their disease. That’s what finally drew me out.

“You know what we really need?” said Linda Montyl, “Lindsay Lohan. That’s who.” She laughed out loud at the thought of recruiting a notorious actress to boost kidney disease awareness.

Linda Montyl won the California Public Citizen of the Year in 2012 for founding the Westside Kidney Support group. She retains a small amount of kidney function and a large amount of humor about her condition.

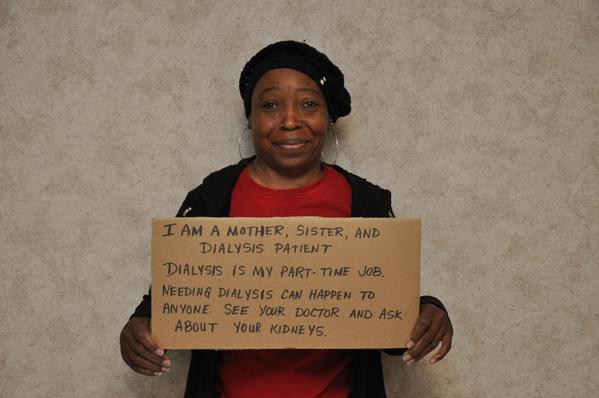

Laura Newsome, sitting to her left, quietly agreed: “We need someone — anyone — to bring attention to the cause of kidney disease.” Demure in stature and blessed with a gorgeous smile, Newsome had her first kidney transplant at the age of seven. At 46, she is on her 3rd, and likely last, kidney transplant.

All present, even those with functional kidneys, nodded their agreement about getting a celebrity spokesperson. After all, 1 out of every 10 people in the U.S. has Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD). For every ten people with CKD, only one of them knows about their condition. Fewer understand what can be done to slow the progression of their disease.

Even people who meet regularly to talk about kidney disease have a lot to learn. A nephrologist named Dr. Stella Feld had just spent an hour with the group explaining how hypertension and diabetes kill kidneys prematurely, and how she uses dialysis to save those who lose kidney function for any reason. What Dr. Feld did not mention is that there are two possible solutions to kidney disease beyond dialysis and transplant. These solutions should inspire people to avoid desperate measures such flying to the Philippines to buy a kidney, or hiring actors of dubious merit to be their spokespeople.

So when Dr. Feld left and Linda Montyl started laughing about Lindsay Lohan, I finally put down my pen and dropped the proverbial bombshell. “There might be a time, not too long from now,” I said, “when we’ll be able to replace your kidneys… with kidneys that are also yours.”

At rest, the average adult breathes every 3-5 seconds. Almost 10 seconds passed before someone in the room said, “How?”

For the next few minutes, before the group dispersed and I became a journalist again, we talked about kidney replacement, but not the traditional type, with hoses, blood and filters, like Dr. Feld does for a living. We talked about the ultramodern type of replacement, with sleek 3D printers and organs made to order. This kind of replacement takes overcrowded dialysis centers off the table, and, ultimately, may be our best shot at avoiding a healthcare disaster – a far worse disaster than the one currently in progress.

Spotlight

How kidney disease has remained out of the spotlight is a social and medical mystery. Every year Medicare pays more than $45 billion to treat declining kidney function. Any preventable disease responsible for a bill that size strikes me as phenomenally worth paying attention to. Add in the body count (47,000 per year and climbing) and something becomes rapidly clear: much as HIV/AIDS did for many years, kidney disease suffers from a grave silence in the face of overwhelming loss.

So what are the reasons for the silence? True, kidney disease lacks major celebrity sponsorship, but it still affects 31 million people in the U.S. (for HIV, that number is 1.2 million). When 1-out-of-4 people over the age of 60 have a life-threatening disease in common, how is it possible that so few know about it?

A Stroll As the Ship Sinks

Imagine strolling around the deck of a rapidly sinking ship. Now imagine that half of the souls on that ship feel no impending sense of doom whatsoever. Another quarter think that maybe they should start wandering towards the lifeboats sometime soon. That’s where we’re at with kidney disease. Only 26 percent of those at-risk for the disease feel at-risk. Worse, 56 percent inexplicably feel that their risk is “lower than average.”

These facts become stranger when you consider that most people are familiar with the two major risk factors for kidney disease: high blood pressure and diabetes. It probably wouldn’t surprise most Americans to hear that 30 percent of the U.S. population has high blood pressure. Not many would be shocked to learn that 10 percent of us have diabetes (in some populations, that number is much higher: for example, 25 percent among Mexicans aged 25 to 40 years). This general knowledge about diabetes and high blood pressure doesn’t add up to a broad understanding that 20 million people have kidney disease because of their diabetes and/or hypertension.

“The number one reason that people are on dialysis is diabetes,” Dr. Feld said to the Westside group. “The number two reason is hypertension.”

What really might really spell disaster for the frigate USS Healthcare System is that addition to the 20 million people whose kidneys have already failed, or nearly failed, another 40 million have kidneys that are starting to fail. There are twice again as many icebergs in this sea as we thought.

Years from now, when the kidneys of 60 million Americans have failed, where will that leave us? Will we have the resources to rescue everyone with dialysis, or will the US be forced to resort to the kind of rationing we see in other countries – the kind of rationing that we used to have, before dialysis became a right under law, where we saved only the few that we could?

Clearly, something should be done before that day arrives. After all, because the factors that cause it are controllable, kidney disease is largely preventable. We should be able to people off the ship before it sinks. But how, when most of the at-risk people don’t think they are at risk, how can we possibly follow the CDC’s advice to Save Our Kidneys (SOK) by having urine and blood tests done on a regular basis?

According to Dr. Feld, if you can get people to understand how kidneys work, you can help them understand why they fail — and maybe, eventually, you can transform kidney disease from an abstract math problem into a serious consideration for everyone who knows someone at risk...

… which, of course, is everyone.

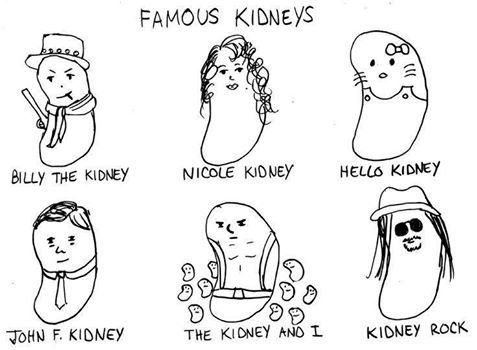

Kidneys, Those Mysterious Bean-Shaped Objects

During her visit, Dr. Feld outlined the critical first step to saving our kidneys. “You have to know your body,” she said, which makes pretty good sense. Most people don’t think they are at risk for kidney disease because most people don’t understand the effect that their high blood pressure and diabetes is having on their kidneys. They don’t understand the effects because… kidneys? Those things that make you pee, right? Well, yes, but — let’s just start from the top, or, in this case, the back.

Like most humans, you probably have two kidneys lodged on either side of your spine. Each of them is about 4-5 inches (10.9-11.2 cm) long and, yes, bean-shaped. Each pink bean weighs about as much as a medium-sized apple. If you could hold a healthy one in your hand, it would feel slightly soft to the touch and dense. This is because each 4-inch kidney is packed with a million tiny groups of cells called nephrons. Nephron is Greek for “kidney”, which is why Dr. Feld is called a nephrologist. Each of these little clusters of cells does the big job for which the apple-sized, bean-shaped organ takes credit.

Nephrons functions a bit like electric coffee makers. Blood percolates through one end. Salt, potassium, sugar and urea, from the protein you eat, are sifted out of the blood and into what later becomes urine. Water is removed or replaced until the concentration is balanced, neither too dilute nor too condensed. That’s why your urine changes color when you drink water.

Healthy kidneys basically brew your blood. In the end, they give back a better version of your blood than they received. Dead or dying kidneys, on the other hand, cause serious problems. Blood pressure increases. Potassium and toxin levels become life threatening, and fluid collects in the extremities. For many people, swelling from that fluid build-up is the first sign something has gone wrong.

“In 2006, I went into the emergency room because my legs were so swollen I could barely walk,” said Lydia, a member of the Westside group who preferred that her last name not be used. Before that say in 2006, Lydia, a diabetic since 1986, had a diet consisting largely of prepared foods. “I used to eat out every meal except breakfast,” she said at the meeting, “It was so much salt.” Eating prepared foods in the way that Lydia described that day is one of the major reasons why diabetes, high blood pressure and kidney disease are on the rise here and around the world. The superabundance of salt and sugar is quite literally killing our kidneys.

At the ER, Lydia was diagnosed for the first time as having a kidney problem. At that point, though, the problem wasn’t just poor function, but outright kidney failure. Again, this is typical of kidney disease. Because each kidney is made up of a million nephrons, they fail by slow and subtle degrees. With kidney disease, the first major sign that the ship is sinking is often that its passengers wake up floating in water. By the time the swelling of the legs occurs, most kidney function is already gone.

Ignorance about how this all works doubles salt’s deadly efficiency. Lydia’s case provides the perfect example: she knew about her diabetes and high blood pressure, but didn’t connect those two diseases with the possibility of kidney failure. That lack of connection allowed her processed food consumption to continue unabated, running her into the iceberg of full-blown kidney failure at full-steam.

Plotting A Course Correction

At the Westside group meeting, Dr. Feld mapped out how kidney disease, which kills more people every year than breast cancer, is largely preventable if people take care of themselves and see a doctor every year. It turns out that a little attention goes a really long way.

Like watchmen in a ship’s pump room, kidneys work overtime to filter excess salt and sugar from our blood. Our kidneys can dump so much sugar into our urine that it ends up smelling, and tasting, sweet. Prior to modern times and modern lab tests, one of the ways to tell if someone was diabetic would be to taste their urine. (Fortunately for Dr. Feld and me, these days are long gone.) The Herculean labors of the kidney have been immortalized by the disease name itself: diabetes mellitus, the sickness that makes patients pass sweet urine.

Try as they might, like a crew nearing exhaustion, kidneys can only keep pace with our diets for so long. Sugar, the stuff you buy by the pound in the store, rises to a level in the blood so high that it overwhelms the kidneys’ ability to clear it out. Individual sugar molecules then push into tissues, invading organs from head to toe. That’s where the real trouble starts. Like salt, sugar drags water along behind it. Where the sugar goes, water follows, creating swelling.

When her kidneys lost the fight against sugar and salt, Lydia’s swollen legs were the most visible result, but not the only ones by any means. That same water-following-sugar effect swells and bursts the small blood vessels of the eyes, the toes and, of course, the kidneys themselves. What follows is blindness, foot and toe amputation, and, almost inevitably, life on dialysis. This damage is the part of the diabetes/hypertension iceberg that you can’t see until it’s too late.

“I always tell patients, ‘Your kidneys are like delicate flowers that just want to be lightly sprayed’,” said Feld, “’When you have high blood pressure, it’s like you are hosing down those flowers, crushing them’.”

Like a vessel firing red flares into the night, as millions of nephrons are silently crushed, they send out distress signals. These signals can be picked up in simple blood and urine tests – the ones the CDC wants everyone with diabetes and high blood pressure to have every single year.

So what’s stopping us from detecting the signals and saving all those kidneys? We are, of course. Sadly, only about half of the people in the US see a physician every year, and that number is dropping. Even people with major risk factors skip yearly visits. When they do finally go, the news can be dire.

“Five years ago, I went to see my doctor for a routine check,” said John Hegun at the Westside meeting. Hegun felt perfectly well that day, but had suffered from high blood pressure for years. “They told me I had serious kidney disease."

A few months after his original diagnosis, Hegun began a life-saving course of dialysis, the original and most widely utilized form of organ replacement in the world.

Dialysis: The First Replacement

The word dialysis is a good description of what kidneys do for a living. Dia and lysis are two Greek words that, when you put them together, mean “separation.” Dialysis separates undesirable fluid, salts and sugar from the blood, just as the kidneys would if they were still working. Since its invention around WWII, dialysis has ballooned into a $24 billion dollar a year industry.

A few lucky folks, like Hegun, can dialyze at home. Linda Montyl, Lydia and more than 400,000 others spend 3-5 days out of every week in a dialysis center. Being hooked up to machines up to 8 hours a day makes it possible for them to live. It also makes it nearly impossible for them to work full time, take a vacation or making long-term plans. Thus, most kidney patients are eager for a transplant.

While dialysis is something that Dr. Feld, or I, could order for you any day, transplant is a challenge of an entirely different kind. For someone with no kidneys to receive a transplant, someone else with kidneys has to surrender one.

Transplant: The Second Replacement

Transplants, especially kidney transplants, save thousands of lives every year. Last year alone, approximately 16,000 people in the U.S. received kidneys from living and deceased donors. That’s the good news.

The not-so-good news is that for every person who received a kidney, there were 5-6 people who didn’t. More than 90,000 people were left waiting for a kidney transplant last year, and the list grows every day. Even in states with heavy organ donation enrollment, like California, where 1-in-3 people are registered organ donors, the wait for a kidney is 4-6 years. The wait is longer for people of color, for whom there are fewer compatible donors. A dozen people of every race and culture died in the U.S. today, as they do every day, waiting for an organ that never arrived.

When transplants do arrive, it’s cause for celebration as well as a moment to reflect. Like the people from whom they come, donated organs have a limited lifespan. The younger someone is when he or she receives their first transplant, the more likely it is that they will need more than one.

Because rejection is common, matches difficult to find, and organs scarce, researchers like Dr. Giuseppe Orlando at Wake Forest University are trying to make us new organs from scratch. If successful, Orlando’s effort at replacement using our own cells would result in organs that our bodies wouldn’t reject. It would be the ultimate win-win. It’s also what prompted me to say to the Westside group, “There might be a time, not too long from now, when we’ll be able to replace your kidneys with kidneys that are also yours.”

The Replacement Matrix

In a perfect world, we would replace Lydia’s, Hegun’s, and half a million other kidneys not with machines or with other peoples’ organs, but with their very own cells. That’s essentially what Orlando and other Organ and Tissue Regeneration specialists do. They take your cells and turn them into whole, functioning organs.

“Tissue regeneration is booming,” said Orlando, last October, “More than 200 patients have received body parts that have been engineered from their own cells.”

To engineer new organs, Orlando and his team use a combination of stem cell technology and tissue recycling. The process begins with a donated kidney whose cells aren’t a match for anyone on the waiting list. In Orlando’s lab, all the donor’s cells are stripped away using a sort of fancy dishwasher. The part of the kidney that’s left behind after the donor cells are removed is called the matrix, or scaffold.

This matrix is a lot like the scaffold of a building. It provides organization for the rest of the structure, which, in this case, is a new, or at least lightly used, organ. Orlando and his team then place stem cells onto the matrix. These stem cells seed the matrix. Like seeds in a garden, they grow into nephrons. In the end, there is a brand new kidney. Or, there will be, once Organ and Tissue Replacement researchers master the process.

“Compared with bladders and tracheas, solid organs like the kidney and the pancreas are another level of complexity,” said Orlando. Growing hollow organs like bladders and larynxes laid the groundwork for Orlando and others to take tissue regeneration to the next level. He hopes that he and his team will partially seed a kidney matrix sometime in the next five years.

“When it’s ready,” said Hegun, “sign me up.”

At the meeting, I didn’t mention an obvious drawback to Orlando’s method: it still requires someone to give up a kidney (using animals is another possibility, which comes with this own complexities and potential perils). There is another replacement technique, even further down the road, but still in sight, that doesn’t require a donor organ. This technique starts completely from scratch and builds a new kidney, cell by cell by cell. In that sense, 3D organ printing of organs, also called bioprinting, trumps matrix-seeding as the ultimate replacement technique, though it, too, faces a few challenges.

Assembly Line Replacement: Organs Made Fresh to Order

Several labs around the world, including a different lab at Wake Forest, are starting to bioprint kidneys. Here’s how it works.

First, the printer is loaded with a cartridge. Instead of ink, the cartridge is full of scaffold cells, just like the kidney matrix is Orlando’s lab. When the 3D bioprinter prints, it spits out one cell at a time, one layer at a time. After several days of printing one cell on top of another in thousands of layers, a pink, hollow, kidney-shaped scaffold is ready to be filled with stem cells. Voila – flip the switch and (a few days later) let the replacement begin.

If organ-printing works, Hegun, Linda Montyl and many others might one day receive brand new kidneys, not re-made ones. Though, as Dr. Feld added later, “3D technology still has a way to go. We would need quite a few cartridges to make the different components of the kidney, and we would have to figure a way to stick the layers together.”

When it comes to printing kidneys, many questions are waiting to be answered. To begin with, the cost is totally unknown. Once cost is determined, the next $100 million (or more) question will be: will insurance cover it? There’s also the small fact that we’ve never seen one of these printed kidneys work. Thus far, bioprinting has successfully produced skin, bone, pieces of vessels and tracheas, as well as replacement heart tissue. Bioprinting has yet to give rise to a fully functional kidney, or any solid organ for that matter.

While we’re sitting here waiting for the technology to mature and grow us new kidneys, there is something we can do. It’s inexpensive, effective, and will help pass the time while possibly saving a Titanic’s worth of people every month. That’s the disaster we can try to avert, ladies and gentlemen – starting right now.

In the Waiting Room: You Are the Replacement

There is no replacement for knowing about your body. When I asked Dr. Joseph Vassalotti, the National Kidney Foundation's Chief Medical Officer, what he though most people know about their kidneys, he said, “I think most people know that the kidneys make urine.” What did he say when I asked him what everyone should know? “That kidneys keep you healthy,” he replied without hesitation. “They are absolutely required for good health.”

By reading this article right now you understand better than most how kidneys work. You know that they play a critical role in our health. You know that new forms of kidney replacement will probably take shape in the next decade or two, and, in the meanwhile, a simple blood test or urine test is the modern equivalent of dodging a bullet. It’s not a sexy or as simple as pressing a button, but until we actually can print kidneys, getting tested is the way to go.

“I think that people have sort of a negative fatalistic view of kidney disease,” said Vassalotti, “But if you have early diagnosis, you can plan better and you can explore options.”

For now, knowledge and prevention are the best replacement. Getting your kidneys checked every year could save you an organ or two. If we literally all go get them checked annually, that could save close to 600 million bean-shaped organs. This number of people getting checked every year would keep Dr. Feld and me pretty busy, but would keep you healthy, and make the folks at the Westside meeting really happy.

A few minutes after I broke my cover with strange comments about someday growing everyone a new kidney, the meeting began to break up. I scrambled to get back into reporter mode. John Hegun gave me the number of his personal physician, in case I had any questions for my story. Linda Newsome packed the sandwiches and trifle into a cooler.

“I’m no Lindsey Lohan,” I said. Laura nodded. She pushed the brochure into my hand asked again for my help in getting the word out.

You and I may not be movie stars capable of attracting clamoring crowds of paparazzi, but we do each know at least one person who is at risk for kidney disease. For their sake, and for our own, we can grow our own sense of what kidneys are and why they are important, and harvest that knowledge for the benefit of others. They need anyone to help. We are someone.

I told her that she’s got it.

Afterwords

Several weeks later, I received a call from Linda Montyl.

“We’re wondering,” said Montyl, “if you could come speak to the group. When are you available?”

I found myself smiling. It’s not always possible to make a difference as a journalist. It’s not always possible to stay undercover as a doctor. This time, though, when I go to that meeting…

…I may say something about those butter rolls.

Reach Contributor Sheyna E. Gifford here. Follow The Science Desk here.

References

1. Every organ transplant and blood transfusion introduces one person’s body to pieces of another person’s body. The person who receives the transfusion or tissue then forms antibodies to aspects of the donor’s immune system, called antigens. People who have received multiple transplants or transfusions can develop thousands upon thousands of these antibodies. As a result, while gaining time to live in the present, Laura and other transplant recipients rapidly lose the ability to accept other transplants later on.

2. US Renal Data System (2011). USRDS 2011 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. Bethesda, MD

3. "Chronic Kidney Disease." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 5, 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/programs/initiatives/kidney.html.

4. UNITED STATES RENAL DATA SYSTEM. 2011 Annual report: Costs of ESRD. http://www.usrds.org/2013/view/v2_11.aspx.

5. "Deaths: Final Data for 2013." Centers for Disease Control. Detailed Tables for the National Vital Statistics Report (NVSR). January 1, 2013.

6. Plantinga, L., Tuot, D. & Powe, N. Awareness of chronic kidney disease among patients and providers. Advances In Chronic Kidney Disease, 17, 225–36 (2010).

7. IBID

8. Centers for Disease Control: High Blood Pressure Facts. 2009.

http://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm. Accessed 1/11/15

9. This figure pertains to residents of the country of Mexico, not Mexican-Americans, per sé.

10. White, Sarah L., Steven J. Chadban, Stephen Jan, Jeremy R. Chapman, and Alan Cass. 2008. How can we achieve global equity in provision of renal replacement therapy? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86, (3): 229-237.

11. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Fast Facts on Diabetes. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-.... Accessed 1/11/2014

12. Moosa MR, Kidd M. (2006) The dangers of rationing dialysis treatment: The dilemma facing a developing country. Kidney International, 70, 1107–1114. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001750

13. AJKD: Editorial. Family History and Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(1):9-10

14. Emamian SA, Nielsen MB, Pedersen JF & Ytte L. 1993. Kidney dimensions at sonography: correlation with age, sex, and habitus in 665 adult volunteers. American Journal of Roentgenology, 160:1, 83-86

15. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013-2014. Atlanta:

American Cancer Society, Inc. 2013.

16. "Diabetes, High Blood Pressure Raise Kidney Disease Risk." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 1, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/features/WorldKidneyDay/.

17. "Ambulatory Care Use and Physician Office Visits." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 12, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm.

18. "United States Census Bureau." Americans Are Visiting the Doctor Less Frequently, Census Bureau Reports. October 1, 2012. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/health_care_insurance/....

19. UNITED STATES RENAL DATA SYSTEM. "2013 USRDS Annual Data Report." Incidence, Prevalence, Patient Characteristics and Treatment Modalities. 2013. http://www.usrds.org/2013/pdf/v2_ch1_13.pdf.

20. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States.

http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/KUDiseases/pubs/kustats/#12.

21. Laura’s anonymously donated third kidney was such a good match that her doctors have posited that it came from a relative.

22. US Department of Health and Human services. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/kustats/#16

23. Murphy, Sean V. and Anthony Atala. 2014. "3D Bioprinting of Tissues and Organs." Nature Biotechnology 32 (8): 773-785. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2958.

24. 1,517 died on the Titanic. ~100,000 die every year of kidney disease and kidney disease related issues.