'The Missing Pages Of Lewis Carroll' Misses The Truth

What do we remember and how do we remember it? These questions of memory, desire, and the blurred line between the memories of our lives and our fantasies sits at the heart of “The Missing Pages of Lewis Carroll,” a world premiere written by Lily Blau, now playing at The Theatre @ Boston Court.

The play takes as its starting point, missing pages from author Lewis Carroll’s diaries – the author, née Charles Dodgson, kept a record of his life, but three entries from the notebooks, June 27th, 28th, and 29th, 1863 were cut out of the diary before it was given over to the public. Because these pages seem to have covered a stretch of time during which a rift formed between Dodgson and the Liddell family, including Alice, they have long fueled speculation that they contain the key to their abrupt separation. While research seems to suggest that the separation was likely due to a rumored relationship between Dodgson and either the Liddell family nanny or eldest sister Ina (or perhaps, even Mrs. Liddell, also named Ina), many have jumped on these missing pages as a sin of omission and the destroyed evidence of inappropriate feelings for the young Alice.

I, personally, have always found claims that Dodgson might have harbored pedophilic tendencies tiresome – there is no proof whatsoever that Dodgson might have held these feelings other than our contemporary mistrust of a middle-aged man’s interest in children and the abrupt end to his relationship with Alice and the Liddell family. People who believe Dodgson had the aims, and perhaps, the actions of a child molester seek to place a contemporary lens on the morals, actions, and perceptions of a Victorian world they don’t fully understand. We can never hope to know the truth of the intricacies of Dodgson’s relationship with Alice and the Liddell family or the reason for his retreat from her life – partly because we have no evidence and partly because it is unfair to place modern perceptions and prejudices on a very different time. The real Alice Liddell herself said in later years that she had only very hazy memories of her time with Dodgson.

SEE ALSO: 'Ballet 422' Goes Behind The Scenes Of Dancemaking

Given all this, I was wary going into this play – prepared to see Dodgson portrayed as a scheming or malicious manipulator of young girls. The play does present a more nuanced narrative than this, but it is also dangerously inaccurate, suggesting many events and feelings that completely disregard historical fact.

It still aims to suggest that there were inappropriate feelings between Dodgson (Leo Marks) and Alice (Corryn Cummins) that ultimately led to their separation. It takes care to place any actual physical contact – kissing and ultimately, rape – solely within the realm of fantasy and memory, but the play moves so fluidly between what it presents as reality and fantasy that it would be easy to walk away with the wrong impression. We are meant to think that Dodgson might have desired or imagined such actions, but never led to believe he went to the extreme of acting on them. It asks us instead to consider how memory and desire might tear us apart and profoundly affect us even when never acted upon – guilt and its havoc upon our memory sit at the heart of the questions the play asks us to consider.

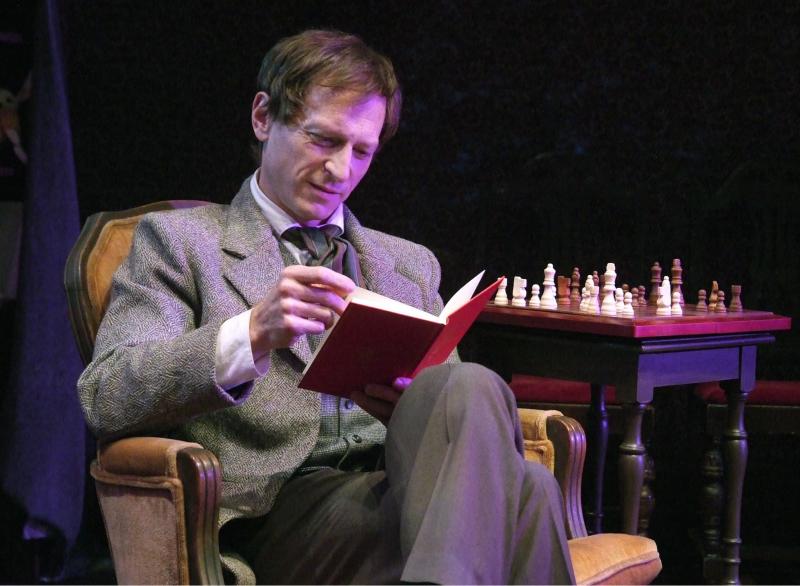

Dodgson’s softening is due to the strength of Leo Marks’ performance, though the actions of the character in this play differ widely in parts from historical reports of the man. He expertly conveys the guilt and agony of a man torn apart by feelings he could not understand or act upon. Scholars often note that Dodgson was nervous and possessed a childlike innocence in his view of the world, which led him to find comfort in the company of children. Marks conveys Dodgson’s discomfort in the adult world with a simple, almost subconscious tell – when speaking with adults and the Liddell parents, he speaks with Dodgson’s notorious stutter that resulted in shyness throughout his life. However, when he is accompanied only by Alice and the characters of his imagination, his stutter disappears. His natural gravitation towards children and nuanced innocence are shattered by guilt and self-loathing, and Marks displays both sides of this complicated man expertly.

SEE ALSO: Has Actors' Equity Sounded A Death Knell For Small L.A. Theaters?

Stephen Gifford’s scenic design transforms the theater into this Victorian world, and the set’s constant pull between outside and inside enhance the lack of coherency in time and place that the play’s focus on memory and fantasy demands. When you enter, it seems a modest, but slightly dull Victorian living room, but quickly, the White Rabbit (Jeff Marlow) comes out of a hole in the ground, the walls are revealed to be a scrim, and then partially disappear altogether to reveal a lush garden of ivy-covered walls. Small theaters are often limited in budget when it comes to scenic design, but Gifford takes the sets in this production to a new and impressive level.

The play also makes loving homage to Carroll’s stories in its staging. When we first see Alice in the recesses of Dodgson’s memories, she appears behind a scrim as if suspended in mid-air, echoing her fall down the rabbit hole. Real people in Alice and Dodgson’s life appear in the garb of the White Rabbit and the Queen of Hearts, emphasizing how Dodgson first created the story specifically for Alice, spinning characters as inspired by people they actually knew in Oxford. The most poignant tie between Carroll’s published work and the staging comes when Alice removes her iconic blue dress from the sitting room cabinet, which is also a mirror – in a brief tableau, she recreates the image of Alice going “through the looking glass.” (Although a small grumble, the blue dress was not popularized until the Disney adaptation of the film, and the Tenniel illustrations published with the book were in black and white, so the emphasis on the blue dress is yet another misrepresentation of historical fact).

Despite all the strength of the production, the play and its writing ultimately fell flat in what it aimed to convey. In not taking care to maintain historical accuracy of other parts of Dodgson and the Liddell’s life, it makes the liberties it takes with Dodgson’s relationship with Alice seem even more irresponsible and unfounded.

Reflecting on her young self and desires, Alice says, “I don’t suppose any woman can love quite as madly as a girl of 11.” Anyone who experienced the agony of a pre-teen crush can relate to this statement – when we are young, we often are overwhelmed by the strength of our emotions and can confuse feelings of affection and trust for the violent throes of love. The play strives to portray Dodgson not as an aggressor, but as a man equally as lost as an 11 year old girl who doesn’t understand her feelings for the first man in her life outside of her family. Alice initiates things because of feelings she can’t understand and that draws Dodgson into a web of guilt and desire.

Yet, we completely lose the nuances of the confusing passions of an 11-year-old girl because of a casting choice. I have no desire to fault Corryn Cummins’ performance as Alice – she is always fully believable and lovely. Yet, in her casting, we lose the picture of Alice the play wants us to have: a confused young girl suddenly overwhelmed by feelings she’s never experienced.

Despite masking her with pinafores, it is hard to deny that Cummins is a woman not a girl. When Alice becomes an object of desire, Cummins’ age makes it impossible for the audience to see her as anything but an overtly sexualized being. She initiates most of the contact and tension between her and Dodgson, but because Cummins is an adult woman, Alice reads much more as a seductress than a confused little girl.

SEE ALSO: Varied & Vibrant: Meet USC's MFA Acting Class Of 2015

For a whole host of reasons, including the physical contact portrayed between Alice and Dodgson, it might not be reasonable to cast a young girl in the role. However, the play cannot succeed in its aims and themes (however erroneous) otherwise. This is never more clear than in the final scene; Cummins delivers a stunning emotional conclusion. She is permitted to portray a womanly Alice, grown far from the child she once was, though still smarting from the emotional wounds of her young love for Dodgson. The final scene packs an emotional wallop, but it’s like the Cheshire Cat – a smile with no body behind it to support it.

Ultimately, the production itself is strong, buoyed by strong performances and scenic design. The play is a world premiere, and like much new work, still needs to have some things clarified and reworked. Even mild fans of Carroll might find the implications and blatant historical inaccuracies frustrating to watch. And for those who don’t know any better, they run the danger of leaving the theater with an extremely stilted and erroneous view of Carroll. Yet, I can’t deny that it sends you home pondering questions of love, guilt, memory, and desire – and really, what more can you ask from theatre, then to send you down a rabbit hole – I just wish it were a less absurd one.

"The Missing Pages of Lewis Carroll" is playing at The Theatre @ Boston Court (70 North Mentor Avenue, Pasadena) through March 1st. Tickets start at $34. For more information visit BostonCourt.com

Contact Staff Reporter Maureen Lee Lenker here or follow her on twitter @maureenlee89

For more Theater & Dance coverage click here