Exposing Gary Hart And The Future Of Political Journalism

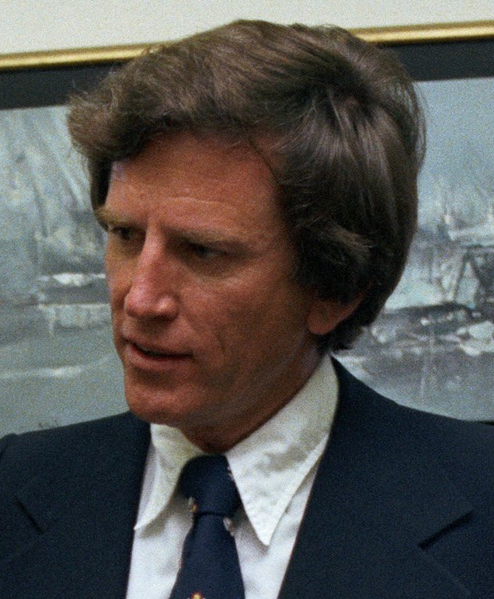

The question posed in the 1984 Wendy’s commercial became a pre-Internet sensation, a pop culture catchphrase in the dinosaur days when broadcast media ruled the airwaves. Democratic presidential contender and presumed nominee Walter Mondale borrowed the phrase to question rival Gary Hart’s ideas and, by extension, the substance behind the Colorado senator’s insurgent campaign.

Political journalist Matt Bai asks the same question three decades later in a recently published book, All the Truth is Out: The Week Politics went Tabloid, recounting Hart’s spectacular and scandalous plummet from his political pedestal. However, the question isn’t directed to Hart, but at commonplace tactics and practices of contemporary political journalism. While Hart’s fall sets the stage for Bai’s narrative, the broader premise is that that Hart was collateral damage, with political journalism and the American public the primary casualties.

Bai, the former New York Times Magazine political guru and current Yahoo News political scribe, examines the catalytic forces and circumstances that included technological innovations and changed cultural attitudes that enabled Hart’s fall.

SEE ALSO: Women At The Polls: Are The Tides Turning?

Mondale’s numbing defeat by Ronald Reagan in 1984 positioned Hart’s as the Democratic frontrunner in the next presidential contest, a status bolstered by polls and expectations. Then, in May 1987, several Miami Herald journalists staked out Hart’s Georgetown townhouse, investigating a telephone tip that purported Hart was indeed the philanderer rumors suggested.

After reporters observed Hart with a young woman matching the tipster’s description in and around his townhouse, they attempted to tail the twosome as they exited the residence but ended up confronting the candidate, who appeared agitated and evasive. The resultant scoop toppled Hart’s ambitions within a week.

Bai argues that previously sacrosanct journalistic ethics, practices and substance fell alongside Hart’s candidacy, opening the door to reducing politics and public service to a Hollywood spectacle.

While the National Enquirer published the infamous Monkey Business photo (the enduring public image of Hart’s legacy), Bai pinpoints the Hart affair as the moment mainstream media also ventured into tabloid territory, metaphorically and almost literally, peeping and prying into politicians’ bedrooms and personal lives under cover of investigating and exposing relevant ethical misdeeds.

Then there was the ensuing media assault launched with helicopters and press conferences. While Bernstein and Woodward set the ideal for modern journalism, the actual post-Hart era efforts of some recent journalistic practices resemble Waterloo more than Watergate in Bai’s account.

Unlike Nixon, Hart wasn’t a deposed king. His political demise happened even before the Democratic party could crown the presumptive nominee. However, like the Watergate affair, Bai attributes Hart’s downfall with initiating the seismic changes in journalistic attitudes and practices, not to mention influencing public attitudes and expectations.

This book should be required reading for not only journalism and political science students, but also for a broader American public accustomed to sound bites, scripted productions and scintillating but superficial entertainment that doesn’t distinguish between Hollywood and Washington; showbiz celebrities and political leaders.

People wondered why Bai would devote an entire book to an aged scandal and protagonist that many barely recall save for that Monkey Business, if they do at all.

Hart is a footnote in presidential politics, a face and a name that only occasionally surface. And, as Bai notes, those times of remembrance and mention often occur following the latest political sex scandal. That is the reason Bai bases his exegesis on the dated controversy.

He argues that even though the nation has buried the particulars of that scandalous week beneath nearly three decades of subsequent scandals, the consequences live on.

Bai is a master of what is termed narrative nonfiction, and the book is a gripping analysis of political and social nuance and context. Most of all, the book examines spectacular talent and ambition, at once energized and sabotaged by human tendencies, temptations and shortcomings – both those of Hart and the journalists that Bai asserts rearranged America’s political landscape.

Bai responded to several questions in an email exchange on the book, expanding on the book’s overall subject and the after effects in today’s media and political environment.

Q: You highlight Watergate, technological innovations and cultural shifts as catalysts for the salacious scandals and scripted superficialities common in today’s political new environment. Do you think that the metaphorical marriage of politics and Hollywood–epitomized by Ronald Reagan’s inauguration–also portended what followed seven years later with Gary Hart’s downfall?

A: Well, as I say in the book, I think Reagan was more illustrative of what was happening in the culture than he was an influence on it. Television had really reached its political zenith by the 1980s, and the Reagan phenomenon was a product of that, because the moment played so well to his particular set of talents. So in that sense, yes, Reagan definitely stood at the intersection politics and celebrity, and it was probably inevitable from that point on that our politicians would be treated like celebrities. All of these things were converging at once.

Q: Ronald Reagan is recalled as the Great Communicator more than lighthearted career efforts like Bedtime for Bonzo while Gary Hart is remembered more for the Monkey Business rather than serious endeavors like The Fourth Power: A New Grand Strategy for the United States in the 21st century. What does this say about both society and the news media that informs it?

A: More than anything, it probably means that you’re remembered for the last famous thing you did, not what came before. And maybe also that in the TV age, leaders became etched in their defining moments. We remember Reagan at the Berlin Wall. And we remember Hart on that dock.

Q: Corporate communication strategies consist of simple stories and fables that stick. I see a lot of the same marketing in political sound bites and sticking points. Along with the entertainment factor, is political journalism becoming an extension of corporate communication selling a politician rather than a product or brand?

A: I wouldn’t take so broad a view. There’s a lot of awfully good political journalism today. I think a lot of the partisan sites could probably fairly be accused of selling an ideology.

Q: As you explain in the book, political campaigns have email lists and Twitter to control their message. They can also get widespread exposure through scripted press releases in the form of blog posts on online media like Huffington Post. What incentive does a campaign have to grant an unconditional interview with a reporter?

A: I don’t think they manage to persuade anyone using those tools. And they may think they don’t need to, but our recent history of very tumultuous politics and ever shifting majorities suggests otherwise. In the end, though, it really comes down to responsibility. The politicians I’ve known whom I most respect sat down and made their case with reporters because they believed they had an obligation to make themselves understood in some length and to people who didn’t necessarily agree with them already. They had the confidence in their ideas to go out and explain them and fight for them. We should aspire to leaders like that. Politics is about more than winning elections.

Reach Contributor Wayne Trujillo here.