A Briefing On 'Big Eyes': Get Ready For Tim Burton's New Biopic

Except it wasn’t Walter doing the painting at all; it was his wife, Margaret, who for years let Walter put his name on her works in one of the biggest cover-ups in art history.

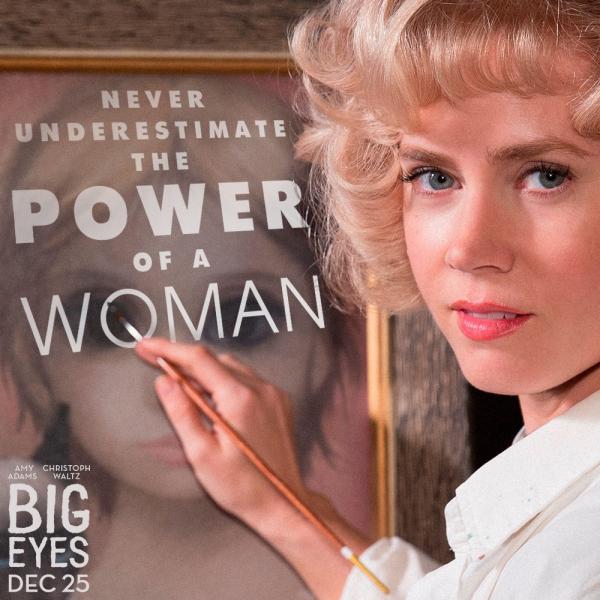

Margaret Keane is the subject of “Big Eyes,” a new Tim Burton biopic coming out on Christmas Day. Her story is a blockbuster-worthy one of abuse, regret and eventual triumph. Between Keane's inspiration, Amy Adams' acting and Lana Del Rey's soundtrack, the movie packs a solid girl-power punch.

READ MORE: No Budget Film Festival Urges Filmmakers To 'Never Stop Shooting'

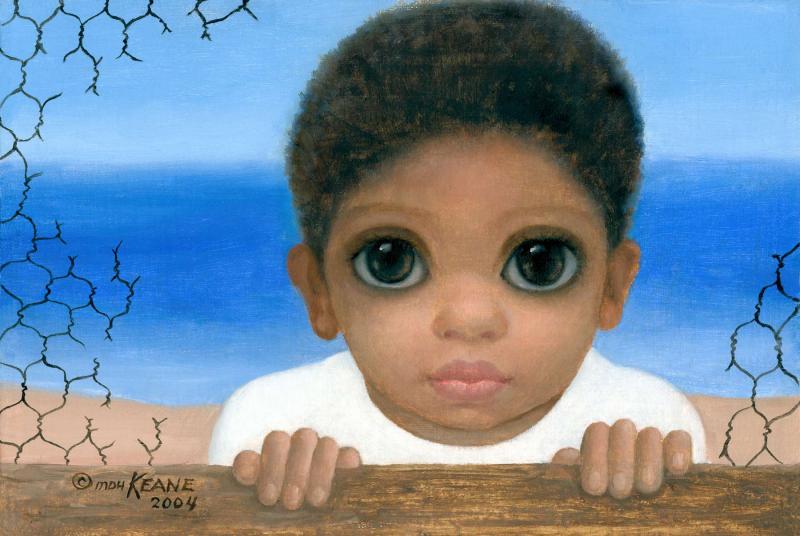

To fully appreciate "Big Eyes," it's crucial to understand how Keane's artworks fit into modern art history: how and why some kitschy paintings of children with big eyes became an enduring influence in American art. Here's what you need to know:

Keane’s work emerged during the denouement of masculine abstraction. Artists like Pollock and Rothko expressed raw, visceral feeling through powerful splashes of color on canvas. The works pointed to the buried emotions and tangled complexities of the artist’s psyche. Next to one of Pollock’s chaos compositions, Keane’s works looked like figurative trash: too sweet, too kitschy. Too easy.

“It dawned on me that I was painting my own inner emotions,” said Keane in an interview with The New York Times. Keane was sad, the children she painted were sad – where was the depth, the intellectual rigor in that? Keane’s paintings were to high art as “Twilight” is to the Great American Novel.

New York Times art critic John Canaday called a Keane painting “tasteless hack work,” but what infuriated critics most is how popular that taste was with the public; Keane’s big-eye paintings and their knockoffs permeated pop culture. “By the early 1960s, Keane prints and postcards were selling in the millions,” says The Guardian. People Magazine called Keane’s work “perhaps the best-selling art in the Western world” during the sixties.

By the time Keane’s work debuted, the Abstract Expressionist movement was losing ground to a new kind of art: Pop Art, spearheaded by Andy Warhol and his Campbell’s soup cans, was flat, fun and unapologetically commercial. America was spreading into suburbs and shopping malls. As Adam Parfrey and Cletus Nelson explain in their book "Citizen Keane," adults with money to spend and walls to decorate were looking for art they understood.

Warhol said of Keane, ''I think what Keane has done is just terrific. It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn't like it.'' Trapped in this statement is the dark side of Pop Art – Warhol’s soup cans are fun, yes, but they’re also a statement mourning the commodification of life. The sixties were full of upheaval as much as prosperity, loss as much as gain. Keane’s melancholy “waifs” struck a chord with conflicted consumers.

Walter Keane shrewdly tapped into this market. After he and Margaret met in the mid-‘50s, he started secretly selling her paintings at a nightclub in San Francisco. “One night Margaret decided to go to the club with him,” says Jon Ronson in The Guardian. “He had me sitting in a corner,” Margaret told Ronson, “and he was over there, talking, selling paintings, when somebody walked over to me and said: ‘Do you paint too?’ And I suddenly thought – just horrible shock – ‘Is he taking credit for my paintings?’”

Walter tried to justify his actions to Margaret. “People don’t want to think I can’t paint and need to have my wife paint,” Margaret says Walter told her. He was pointing to an unfortunate reality, one that continues to plague art practice to this day: women were and continue to be tragically underrepresented in art galleries, museums and history textbooks. Would the paintings have sold as well if people had known they were painted by a woman? Maybe not.

Margaret tried to fight it at first, but eventually she gave in. Painting sales took off because of Walter’s shrewd marketing and “self-inflation,” and the Keanes got richer and richer. Soon, Walter was living the life of a rock star.

“We’d have parties until four in the morning,” he wrote in his memoir. “Dinner, drinks, anything they wanted. Always three or four people swimming nude in the pool. Everybody was screwing everybody. Sometimes I’d be going to bed, and there’d be three girls in the bed.”

Meanwhile, Margaret was hidden away in the studio.

“The door was always locked. The curtains closed,” she told The Guardian. “When he wasn’t home he’d usually call every hour to make sure I hadn’t gone out. I was in jail.”

Walter pressured her to produce more and more paintings, and soon they were almost as famous as Pollocks and Rothkos.

“Keane art was seemingly everywhere—from the sales bins at Woolworths to the gilded mansions of Hollywood royalty,” say Parfrey and Nelson.

Keane was even commissioned by the 1964 World’s Fair to paint a “masterwork” called “Tomorrow Forever” for their Pavilion of Education. Walter, who never missed an opportunity to self-promote, started telling people he was a descendant of the Old Masters. In his memoir, Walter said that his grandmother “told him in a vision that ‘Michelangelo has put your name up for nomination as a member of our inner circle saying that your masterwork Tomorrow Forever will live in the hearts and minds of men as has his work on the Sistine chapel.’”

According to The Guardian, after The New York Times wrote a scathing review (“This tasteless hack work contains about 100 children and hence it is about 100 times as bad as the average Keane”) the World’s Fair took “Tomorrow Forever” down. Even though the paintings were nearly ubiquitous in consumer culture, critics still disdained Keane's works as plebeian.

In Hawaii, supported by a new husband and new religion, Margaret discovered a strength and courage she didn't know she had. She decided to get back what was rightfully hers. In 1970, she challenged Walter to a “paint-off” in San Francisco’s Union Square. Walter was a no-show, but Margaret sat down and painted a classic big-eyes portrait in front of reporters and TV cameras, cementing public opinion on her side.

In 1986 after USA Today published an article attributing the paintings to Walter, Margaret won a second paint-off, this one in front of a judge. She sued Walter and USA Today, winning $4 million and the rights to sell her work. Although she never saw the money, as Walter “drunk his fortune away,” she was able to open the Keane Eyes Gallery in San Francisco, which still sells her paintings.

They don’t fetch quite as much money today – the big eyes paintings went out of style in the ‘70s – but in the late ‘90s Keane enjoyed a renaissance. Tim Burton was collecting her paintings as early as 1999, and the big eyes have arguably had quite an influence on the aesthetics of Burton's work, especially films like "Corpse Bride" and "The Nightmare Before Christmas."

“That art is very much burned in our subconscious and haunts us to this day,” says Burton in Vogue.

The psychological torment Keane went through fascinates Burton. "It's a quietly complicated story, which I found interesting," he told the L.A. Times. "I just imagine her going along with it and getting trapped in this weird world. Then, also keeping that kind of secret and knowing the work's getting this polarization of opinion — some people loved it and some people violently wanted to rip them off the walls — I liked all that."

According to the L.A. Times, Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, the film's screenwriters, first discovered Keane's story 11 years ago. They originally planned to direct "Big Eyes" themselves, but gave the film to Burton after Christoph Waltz and Amy Adams — both of whom are already gathering awards-season buzz — signed onto the project.

“Big Eyes” debuts on Christmas Day.

Correction: The original version of this story credited Adam Parfrey as the sole author of "Citizen Keane." Adam Parfrey and Cletus Nelson co-authored the book.