Prison Labor: Exploitation Or Rehabilitation?

But it's impossible to evaluate the merits and demerits of prison labor without examining its context: the American criminal justice system. To understand prison labor, we have to understand which populations are subjected to it and why.

Piper Kerman, author of the memoir "Orange is the New Black: My Year in a Women’s Prison," explained in a talk at USC that different groups of Americans are “policed differently, prosecuted differently, and sentenced differently.”

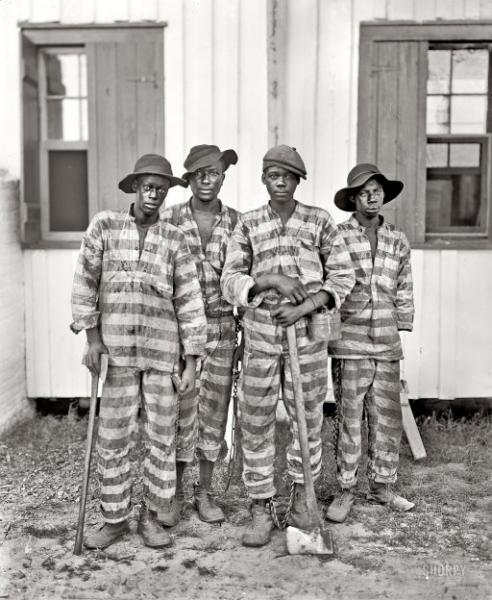

Unfortunately, the color of one's skin plays a huge role in determining these differences, as our modern criminal justice system was built with racist foundations. After the passage of the 13th Amendment, white southerners implemented laws known as “black codes” to maintain the social hierarchy of slavery. These laws criminalized certain activities solely for African Americans. As African Americans became disproportionately represented in prisons, inmates became a new source of cheap, captive labor.

These racist practices have all but disappeared from our criminal justice system. According to a U.S. Sentencing Commission report, black drug offenders are 20 percent more likely to be imprisoned than white drug offenders. Because black individuals are policed, prosecuted, and sentenced so harshly, they are overrepresented as prison laborers.

READ MORE: California Contracts With Private Prisons To Alleviate Overcrowding

Another major defect of our criminal justice system, critics argue, is that it wrongly imposes punishment on millions of people in need of treatment rather than imprisonment.

People with mental illnesses, including drug dependency, are also overrepresented in prisons. A Bureau of Justice Statistics report reveals that 44.8 percent of federal inmates have mental health disorders, a shocking statistic considering that only 10 percent of the general population have mental health disorders. In California, a person with a serious mental illness is almost 4 times more likely to end up in prison/jail than in a hospital. In other words, a person with a serious mental illness is 4 times more likely to be punished than treated.

As for the specific disorder of addiction, the BJS has found that 55 percent of federal inmates are being held for drug violations. Can hard labor really rehabilitate people who are in need of medical treatment?

Piper Kerman argues that the criminal justice system perpetuates social inequities through marginalization. Many people are driven to crime because they are marginalized—be it by racism, classism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, or ableism. As soon as they transgress, these already-marginalized individuals are placed in prisons, which further push them into the periphery of society. Twice marginalized, these individuals leave the criminal justice system only to walk into a third layer of marginalization reserved for former inmates who have been permanently branded as "felons."

READ MORE: CA Prison Reform: Meet The Stakeholders

In prison, all work-eligible inmates are given two options: work or stay locked up in a cell. With such an unattractive alternative, most inmates end up working. The correctional system claims that labor is rehabilitative, alleviating the pressures of marginalization by preparing inmates to reenter the workforce after their release.

But the motivation for putting prisoners to work is not that simple. Both private and government entities are making millions off the huge base of cheap labor that prisoners provide. UNICOR, also known as Federal Prison Industries, is one of many entities putting inmates to work for the supposed goal of rehabilitation. Created by Congress in 1934, UNICOR sells inmate-made products to the government—mainly to the Department of Defense—employing 16 percent of all work-eligible inmates in federal prisons.

UNICOR provides inmates jobs in “factory operations” in order to “provide job skills training” and “produce market-priced quality goods and services for sale to the Federal Government.” Inmates working for UNICOR earn 23¢ to $1.15 per hour, a wage that is usually cut in half due to mandatory deductions.

And this is a relatively good situation; UNICOR jobs pay better than most other inmate jobs.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, in 2001, inmates were making office furniture through UNICOR in 18 different prisons for these wages, while the average worker making office furniture outside the prison system was making $13.04. Given that it pays its workers so little, UNICOR’s profits are disconcertingly high. In 2013 alone, UNICOR’s sales amounted to over $533 million.

The profit motive seems too significant to ignore, but the correctional system claims that prison labor is justified by its rehabilitative benefits. So what exactly are the merits of prison labor? Do these merits validate labor practices we would consider inhumane in any other situation?

“You worked underneath a shotgun," said Gray. "They yelled at you all day long, telling you to get back to work."

Gray was also incarcerated in four different Virginia state prisons, where he was again forced to work. “You’re given an option. You can either work or go in isolation," Gray said. "In isolation, they take your shoes; they take your socks; they give you a blanket that’ll itch you to death. They give you cold food that’s not worth eating, and it’s dark all the time. All you have is a bed, two feet of space, and a toilet."

READ MORE: Jerry Brown's Prison Policies: Conservatives Disapprove, Too

On a personal level, Gray feels that working while in prison did nothing to rehabilitate him.

“It didn’t teach me responsibility," said Gray. "I just went back to using drugs. I have never stolen anything. The only crime I’ve ever been arrested for is distribution of drugs. When the drugs stopped, the crime in my life stopped. Prison did nothing to help me build a life.”

Despite countless stories like Gray’s, proponents of prison labor still argue that it enables inmates to learn marketable skills that will help them find jobs after incarceration. But Gretchen Heidemann Whitt, Secretary for A New Way of Life Reentry Project, explains that this doesn't hold true in most cases. Employers usually require applicants to check off a box if they have ever been convicted. The unfortunate reality is that many employers immediately throw out any application with a checked box. Gray’s experience reflects this reality. “With 8 felonies, the work experience didn’t help at all in the outside world," he said.

Whitt also points out that prison labor may be even less useful as job preparation for women because they face intensified obstacles in returning to the workforce.

“There’s a societal mentality that prison is for men, and women who’ve been to prison are morally unrehabilitatable,” Heidemann said. “The idea that these women are fallen women, bad mothers, adds to the stigma of having a criminal record.”

In addition to feeling what can be paralyzing shame due to this stigma, many formerly incarcerated women only qualify for low-paying jobs with few benefits. Given that many of these women are responsible for young children, the cost of childcare outweighs what they would be earning at work. Together, these factors render the job training almost entirely useless in the outside world.

READ MORE: CA Prisons' Use Of Solitary Confinement Hurts Families

Steven Hoss Walters, however, has a different story to tell. Walters was incarcerated in Turbeville Correctional Institution, a South Carolina state prison, between 2003 and 2006. Walters said that he was forced to perform hard labor, cutting grass and picking weeds on fields miles away from the facility he was being held in.

Walters, however, is thankful for what he learned in one of his positions as an inmate worker. Aside from performing hard labor, Walters got to work as a Chaplain’s Clerk.

“The work in the chapel was 100 percent rehabilitative and beneficial," said Walters. "I was given a mentor. I was given examples. I was basically getting therapy everyday.”

Walters’ position was one of privilege. Unfortunately, such a fulfilling job is not available to most prisoners. Of the almost 1,600 inmates in his facility, only 3 got to be Chaplain’s Clerks. "The correctional officers definitely had favoritism toward certain individuals. Who you knew and who you were played a big role in what job you got," admits Walters.

With the communication skills, discipline and professionalism he learned working in prison, Walters got a job at Chick-fil-A after his release.

Certain jobs, like Walters’ job as a Chaplain's Clerk, are undoubtedly rehabilitative by nature. Meaningful opportunities for engagement and growth like this one ought to be more readily available to all inmates. But other jobs—like those that involve toiling away all day in fields, or making military helmets in a factory line—seem to offer no such rehabilitation. Furthermore, what is rehabilitative for one person may not be for the next person. While Walters may have needed work experience and discipline, what Gray needed was comprehensive treatment for his addiction, and no prison could have offered him that.

Paid inhumanely low wages, most inmates are unable to save up enough money while incarcerated to create stable living situations for themselves post-incarceration. Once they are released, the work experience they acquired in prison is usually overshadowed by the mere fact that they are now convicted felons. Given these systematic obstacles, it's important that we not let the pretense of rehabilitation cover up profit-driven exploitation of marginalized populations in the world of prison labor.

Reach Staff Reporter Lorelei Christie here.