A Salty Situation For Proposed Huntington Beach Desalination Facility

The turmoil surrounding the project stems from both the inclusion of open ocean intake pipes that will supply the operation with seawater and whether desalination is a cost-effective solution for Orange County.

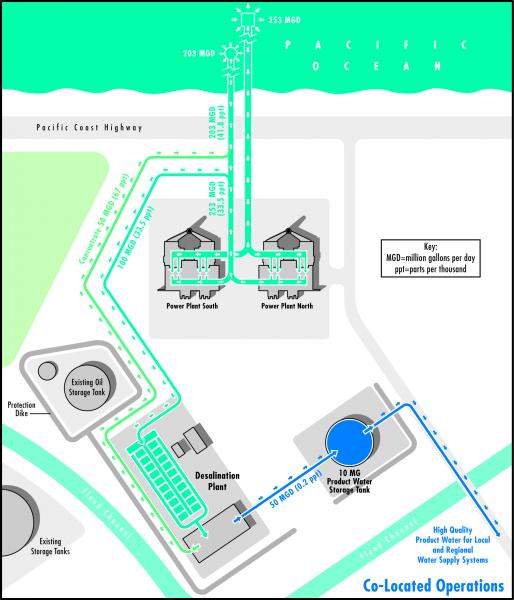

Poseidon Resources, a company that develops large-scale seawater desalination plants, chose to colocate the facility with the AES power plant on PCH in Huntington Beach to capitalize on its existing infrastructure.

“The power plant brings sea water in, cools the turbines, and the seawater goes out,” said Brian Lochrie, President of Communications Lab and communications consultant for Poseidon Water. “When we decided to colocate with power plants, the plan was to use that water. So before the water goes back out to the ocean, we’d pull a portion of it off, desalinate half of it, and half of it would go back out to the ocean.”

The AES power plant is currently permitted to draw 514 million gallons of seawater a day through open ocean intake pipes. But, due to a ruling by the State Water Resources Control Board in 2010 requiring power plants to faze out open ocean intake pipes, AES is now exploring closed cycle and air cooling systems.

Due to an absence of desalination regulation in California, Poseidon intends to use the open ocean intake and outfall pipes—claiming their daily 127 million gallon requirement would pose a less-than-significant impact on sea life.

“The reason the state has told electric power plants they have to stop this, is because they’ve recognized the damage this has done to the marine environment,” said Connie Boardman, council member and previous mayor of Huntington Beach. “Because the organisms that get sucked up are at the bottom of the food web, and when you decimate the bottom of the food web, there is no biomass to support the upper levels, so we’ve seen a decline in fisheries.”

The Marine Life Protection Act, passed by California State Legislature in 1999, has recently created a statewide network of Marine Protected Areas that are delineated to preserve California’s marine ecosystem.

“You have the creation of the Marine Protection Areas, which are designed to have connectivity and to support each other and to replenish,” said Susan Jordan, Director of the California Coastal Protection Network. “It makes absolutely no sense to put an open ocean intake, or to continue to use one that is in proximity to nine MPAs.”

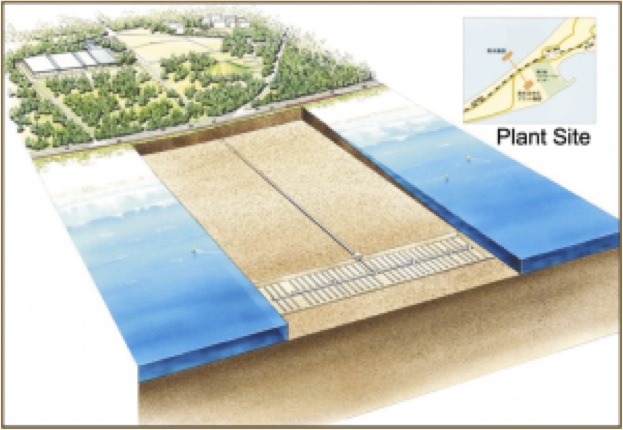

Poseidon argues the subsurface technology would add hundreds of millions of dollars to the project cost and create environmental impacts itself.

“The question is, do the opponents of the project really want subsurface intake, or do they really want to kill the project,” said Lochrie. “Because if they really want to kill the project, this is a good way to do it.”

Environmentalists view the added cost of the subsurface intake as a necessity if the facility plans to move forward.

“You know it’s not our job to maximize their profit, it’s our job to protect the coast,” said Jordan. “[Poseidon] can make money, subsurface infiltration galleries make their money up over time.”

The California State Water Plan requires 257,000 acre-feet of annual seawater desalination by 2025. If approved, the Poseidon desalination project in Huntington Beach will provide 56,000 acre-feet of water a year— enough for about 300,000 people or 8% of Orange County’s yearly water needs.

Both state and local elected officials in Orange County support the project, citing an increase in jobs and tax revenue along with the addition of a drought-proof, locally-controlled water source.

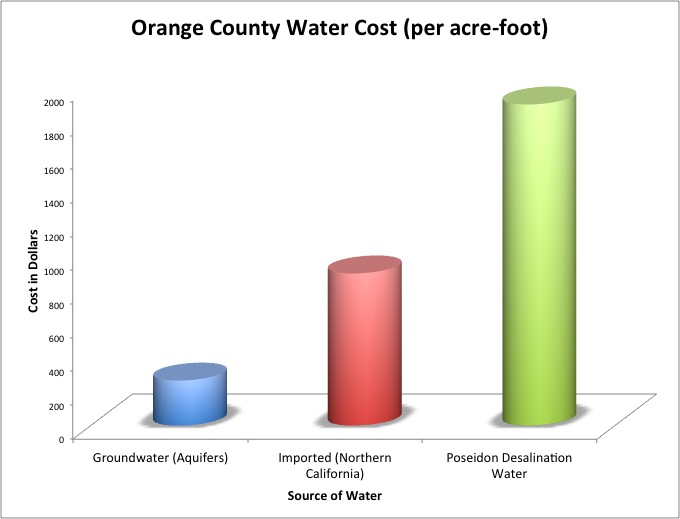

Despite political approval, many community members, environmentalists and non-profit coalitions claim there is no need for the desalinated water, it is too expensive, and the operation is environmentally unsound.

“In Orange County, that has a lot of groundwater, they do a really good job of recycling waste water and putting it back into the ground, and do a good job on conservation, so we’re really questioning whether we need the plant at all,” said Conner Everts, Executive Director of Desal Response Group and Co-Chair of the Southern California Watershed Alliance. “It’s not that we’re against desalination the technology, we’re really for priorities and first things being done first, and desalination [in Huntington Beach] kind of flips that on its head.”

Poseidon’s desalination project is a public-private partnership—meaning Poseidon invests time and money developing and building the project, then a public agency will buy the water.

Poseidon has yet to enter into a water purchase agreement, so the destination of the desalinated water is unclear.

“This water is not for us, it’s for the South County cities like San Juan Capistrano, Rancho Santa Margarita that want to continue urban sprawl that aren’t sitting on an aquifer and rely heavily on imported water,” said Boardman. “So Huntington Beach gets the impacts, San Juan Capistrano, Rancho Santa Margarita may get the water.”

The State Water Resource Control Board is currently developing an Ocean Plan amendment that will address issues correlated with desalinization operations. It is expected to roll out by the end of 2014.

“We think it’s premature to push desalinization plant forward at this point,” said Everts. “We’re hoping that if [the Ocean Plan amendment] doesn’t stop the plant and it’s latest discussion, then at least we get to reevaluate it and lay it out on the table and I think we’ll find, as we found in the last ten years, we don’t need it.”

Based on the results of the subsurface intake study, Poseidon will know whether the project can progress within the next six to nine months.

Reach Staff Reporter Michael Nystrom here. Follow him on Twitter.