Uncounted And Invisible: Homeless Youth In Hollywood

He would unpack his toothbrush, toothpaste, perfume and clothing from the enormous backpack he carried while living on the streets or couch surfing for five years after getting kicked out of his home when he was 13 years old

Now 24, Del Castillo was forced to be independent at an early age, selling Chicklet gum to tourists and washing cars at the age of 5 to help support himself and his mother, who suffered from alcoholism and an abusive relationship. He moved to Los Angeles from Guadalajara, Mexico before his sixth birthday, leaving his mother and five older siblings behind and moving in with his grandmother and other relatives.

“My mom was always drunk, getting abused, I was getting abused, verbally and physically,” said Del Castillo. “All I wanted to do was go to school.”

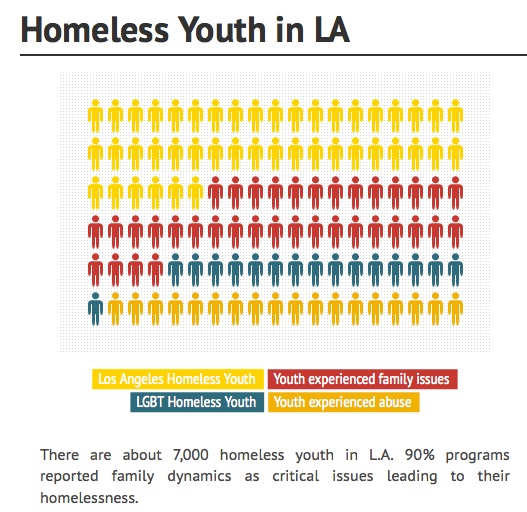

Del Castillo moved in with his grandmother and other relatives in East Los Angeles. And while he says his relatives never treated him well, he never imagined he would be joining the ranks of L.A.’s homeless youth, a large, almost invisible population of about 7,000 people between the ages of 18-24.

After an argument on the night of his 13th birthday his uncles told him to pack his things and leave.

“It was terrible. Very scary,” Del Castillo said quietly. “I would just walk around looking for a safe place, not too dark, not too light, where I knew there would be people around. One night I slept outside a bus stop.”

The Los Angeles Homelessness Authority surveyed 4,000-square miles of L.A. County in one night in 2011 and found close to 4,000 homeless youth, some even as young as 12-years-old, in its first ever attempt to count homeless young adults. More recent tallies peg the number much lower, but homeless experts dispute the figures.

Many homeless youth hang out in Venice and Hollywood, with Hollywood having the highest concentration of LGBT homeless youth and youth like Del Castillo, who were forced into homelessness.

“As soon as I hit Hollywood it was a whole other world,” said Del Castillo, explaining the difference between being homeless in East L.A. and Hollywood. “So many more homeless kids and craziness.”

Last October, the Hollywood Homeless Youth Partnership did a weeklong count and found 460 homeless youth, but youth shelters and services say the surveys and counts are far from accurate.

“Some counts say it looks like homelessness might be declining slightly in Los Angeles,” said Dr. Eric Rice, an assistant professor at the USC School of Social Work who specializes in youth homelessness. “But agencies consistently report that they are seeing more and more people. There are major flaws in counting with homeless youth.”

One major flaw, according to Covenant House, a homeless youth shelter and transition program in Hollywood, is that most homeless youth work hard at being invisible, so numbers of homeless youth are probably much higher than counts show.

“We estimate there are about six to 8,000,” said Covenant House’s communication manager, Steve Daniels.

Youth often hide their homelessness out of embarrassment, Del Castillo explained. Even though he spent several nights sleeping at bus stops, in stairways and even outside of a cemetery, he was “more worried about staying clean so my classmates wouldn’t find out,” he said.

Eddie Camacho, 19, spent 10 days on the street after moving to Los Angeles to go to school and get a job. Born and raised in Pasadena, his family moved back to Mexico when he was 14, but he returned to L.A. after he turned 18 for “more opportunities.”

“I slept at a recreational park in Pasadena after I lost my job and couldn’t pay rent,” Camacho recalled. “I would go to the waterfall and sleep there. One day I slept outside a church.”

Camacho finally told someone about his situation and spent 36 days in an emergency shelter before entering Covenant House’s program.

He is on his way to completing the shelter’s Right of Passage program, a transitional living situation aimed at teaching homeless youth how to support themselves.

Camacho is one of the lucky ones.

Los Angeles has shelter capacity for only 17 percent of the counted 4,000 homeless youth, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Authority, and many drop-in centers have closed down.

“Our wait list could be a day or two weeks,” said Andrew Montejo, the program supervisor at the L.A. Gay and Lesbian Center’s youth services program in Hollywood. “Were pretty much in line with the other services in town in terms of wait lists.”

“There just aren’t enough resources here for everyone,” he added.

The rest couch surf, squat, or stay with strangers, forcing services to expand their definition of homelessness to include most unstable living situations.

Del Castillo spent many of his nights drifting from neighbor to neighbor and used to do his homework in parks or stayed late at school before graduating from Garfield High School in 2006 with honors.

“I didn’t have nobody to share my A’s, my grades, my happiness that I was the first in class, things like that, all the goals I accomplished in my high school,” he said. “I think that was the hardest part.”

While many Hollywood homeless youth want to change their situation and seek help, Daniels says some prefer to stay on the streets rather than enter a shelter for a host of reasons, such as trust issues, drug addiction, or the most common situation, fear of breaking up a pack of youth who travel together and act as a kind of family unit.

Birman has been homeless off and on for the past five years after leaving his family in Grand Rapids, Michigan at the age of 17.

“I decided to leave because I got tired of everybody telling me what I needed to do with my life and what was what,” he said.

Birman has no plans to remedy his homelessness and relies on drop-in centers and church handouts for food and resources, choosing to play guitar outside the Hollywood Chik-Fil-A as a way to make money.

Daniels and other youth services providers cite a difficult family situation as the overwhelming reason most teens are homeless.

Del Castillo’s family also gave him a harder time because he was openly gay, he says, which was another reason why he ended up homeless and has not talked to his family in years.

Like youths of color, those who identify as LGBT are disproportionately represented among homeless youth, especially in Hollywood.

LGBT Homeless Youth In Hollywood

“I learned since I was little that being gay wasn’t going to be easy,” said Del Castillo.

After being on the streets and graduating from Covenant House’s youth program, Del Castillo says he saw “a lot of gay kids who were homeless.”

LGBT youth homelessness is on the rise, says Dr. Rice, and is a “really big problem” that often goes overlooked, as close to 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBT. The number is even higher in Hollywood.

“It is just so disproportionate to the eight-10 percent of the overall population who identify as LGBT,” said Montejo.

Hollywood has also seen a significant jump in LGBT youth seeking services. In his eight years, Montejo said the center used to be overwhelmed by the 30 individual youth who entered the shelter for help.

“Now we see 90-100 every day,” he said, which amounts to about 1,200 a year.

The Hollywood Homeless Youth Partnership found those who identified as LGBT faced different issues and challenges than heterosexual homeless youth.

A UCLA study on LGBT homeless youth found that most centers reported their LGBT youth had more health issues than non-LGBT homeless youth. They are also overwhelmingly more likely to be victims of physical assault, hate crimes, domestic violence, survival sex and drug addiction.

Many more also said they were forced into prostitution.

“It’s easy money,” explained Del Castillo. “The Hollywood community, I think, is responsible for a lot gay people prostituting themselves at a young age.”

Prostitution is one memory Del Castillo files away as a “learning experience.”

“I was 19. It was a very tough experience and I only did it a few times,” he paused. “We all make mistakes.”

Montejo says he sees this story too often. Survival sex is extremely prevalent with his youth, especially for the transgender community, and happens on more corners of the city than people would expect.

“For the last 30 or something years, Highland and Santa Monica Boulevard has been a hot spot for homeless youth and transgender prostitution,” said Montejo.

Daniels said that intersection is one of the most dangerous areas Covenant House’s outreach team visits at night.

“There’s so much illegal activity taking place,” said Daniels. “There’s drugs, and because there’s survival sex there’s money involved, so that brings pimps.”

Methamphetamine use also haunts many of these youth, especially the transgendered homeless population, said Montejo, creating a cycle of drug addiction and prostitution as a means to acquire more drugs.

“I’ve seen many youth who have been in Hollywood for a few months and they have never had to pay for drugs,” said Montejo. “It’s dirt cheap here, like $10 and especially easy to get in Hollywood.”

With so many shelters over capacity, My Friend’s Place reported seeing close to 2,000 different young people every year, the need for more services and intervention programs is dire.

Yet, the deeper question lies in what these youth truly need, and are missing, from their lives before ending up without a permanent home.

Del Castillo had one answer:

“I think the reason a lot of gay people are homeless, do drugs or prostitute themselves is because they don’t have the support of people. But just to find out somebody cares about them; they will feel love. They feel important.”

He paused.

“If they don’t have nobody, they don’t want to be anybody.”

Beds, Jobs And Permanency

Those were the overwhelming responses by different shelters and programs in the area when asked how Los Angeles could reduce its burgeoning population of homeless youth.

Montejo cited the state’s foster care system as the number one issue contributing to the rising number.

“What is that system not doing to prepare these people who emancipate from the program to live independently?” He asked.

Daniels agreed, calling the foster care system a “cookie-cutter situation” and adding that so many youth are bounced around they have never experienced any structure or guidance on how to be a functioning adult.

Los Angeles is also in desperate need of more drop-in centers, since the city currently has four.

Due to several closures, Covenant House has been experiencing an influx of homeless youth that their funds and services cannot cover.

“We are in situations where we get kids who are sleeping in cots in our waiting room areas because that’s the only place we have to put them,” he said. “We’re overflowing.”

In its report, Hollywood Homeless Youth Partnership called for more independent living programs, supportive housing and more mental health services in youth programs.

But at a time when all affordable housing and social services programs are suffering in L.A.’s economic downturn, the needs of homeless youth will most likely continue to slip under the radar.

Del Castillo is now the manager at a Subway restaurant in Beverly Hills, where he has worked for the past six years thanks to an internship opportunity provided by Covenant House.

Daniels says Del Castillo’s success story is uncommon.

“He worked really hard,” said Daniels. “Most kids need to take a few tries to get on their feet.”

Youth like Del Castillo and Camacho remain positive and resilient, understanding the rare opportunity they were given to learn how to become independent young adults.

“I have an internship now,” Camacho said brightly. “By the time it’s over I’ll get a real job.”

Del Castillo is now stable enough to pay his bills and help support his siblings in Mexico, saying he still has the opportunity to make more money in America.

“I don’t want them to be homeless,” he said. “I know how it feels.”

See Octavio Del Castillo's story:

Reach editor-in-chief Brianna Sacks here