Egg Donation: A Rising Solution To Expensive Tuition

This summer Barnett underwent In-Vitro Fertilization, a process in which eggs are harvested from a donor and then combined with sperm to create embryos, which are then placed into the potential child’s “mother.”

The Australian couple—desperate for a baby after many failed attempts—found the USC business major through The Egg Donor Program, a 15-year-old matchmaking agency pairing desirable donors with aspiring parents. The procedure is sold as an advantageous situation for all parties involved: Barnett gets $8,000 to help her with school and the altruistic feeling of helping a loving couple create their family, the Australians will hopefully become pregnant with their first child and the agency makes a profit.

The process is anonymous. Barnett will know nothing about the couple and the couple will never know Barnett’s name or contact information.

More and more collegiate women are willing to market their DNA and sell their eggs, possibly due to a struggling economy.

“With the recent economy I’m afraid of getting a job in the future," said Barnett. "This gives me a security blanket.”

From 2004 to 2010 the number of completed IVF donor cycles in the U.S. increased 82 percent, according to The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, which reports on the growing industry. Robyn Perchik, owner of Beverly Hills Egg Donation, said 75 percent of donors in her database are college students.

Although more women are applying, the process is highly selective.

“We take roughly one out of every 50 people who apply,” said Perchik.

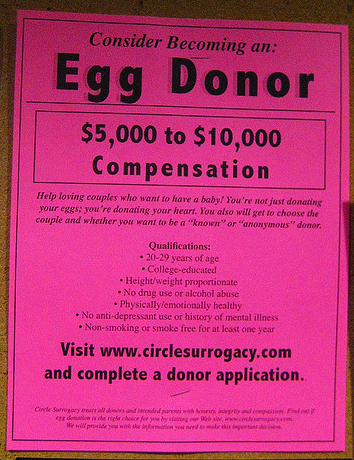

To be successful, agencies need to offer interested couples a large variety of quality donors, which compels the industry to aggressively advertise for new donors on social media platforms and college newspapers.

“We recruit on 2,000 campuses nationwide,” said Perchik. “Sometimes if you’re at the right school or in a good graduate program you might find a little pop-up on the side of your Facebook that says egg donation.”

“The application has personal history, family history, likes and dislikes and many other questions,” said Perchik.

The entire process lasts between two to four months, from applying to receiving a check in the mail.

After agency coordinators pair up donors and recipients—“I’m like match.com for egg donors and couples,” laughed Perchick—the cycle is kicked off with a massive amount of paperwork, testing and synchronizing.

“They make you call a lawyer and sign a contract, do a psychological evaluation, send in even more photos,” said Barnett. “They take a lot of blood to test for drugs and genetic diseases. I also got a vaginal ultrasound to count my follicles (cavities containing an egg in an ovary), which was not fun.” Both Barnett and the recipient mother were put on birth control to sync up their cycles.

Once donors are medically and legally cleared, the real work begins.

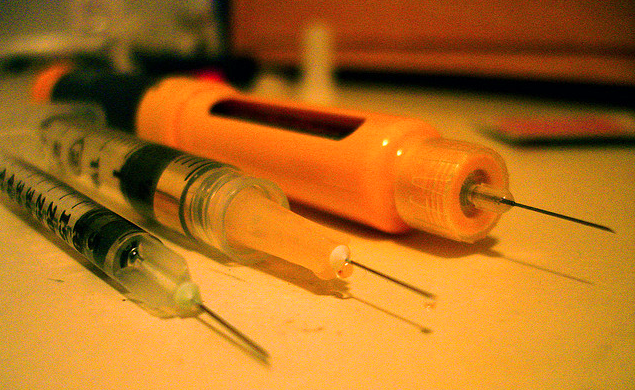

“The first few weeks of shots didn’t affect me that much because I was on birth control before," Barnett said. "IVF resembles that. You are PMS-y and bloaty but nothing unmanageable. The first shots don’t hurt but once I started taking two or three shots a day, the needles were longer, thicker and hurt more. They gave me little bruises on my lower abs."

Although not as time consuming as a normal job, IVF is tricky to fit into students’ schedules. Donors need to attend up to 10 doctor appointments.

“I got up around 6 a.m. in order to make it to class on time,” said Barnett.

Shots need to be taken at the same time every day for four to six weeks, therefore students either need to be home or carry a lunchbox-looking bag around with them filled with the refrigerated medication. Donors also have strict restrictions during the medical process: alcohol, prescription and illegal drugs, sexual activity and strenuous exercise are not permitted. “Not being able to drink with my friends was one of the hardest parts,” said Barnett. “My boyfriend also hates when I do it [egg donation].”

Once the eggs are big enough to be removed, the donor is given instructions on when to take a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) shot, which is taken exactly 34-36 hours before the retrieval surgery and used to stimulate the final growth of the eggs. “By the end I couldn’t do a lot of physical activity, which the agency warned me about. It was a really weird sensation; I felt full of eggs, not pregnant but swollen,” said Barnett.

In normal pregnancy, a fertilized egg travels from an ovary and develops in the uterus. The IVF process puts pressure on a woman’s ovaries, making them do the uterus’s job; the medication forces each ovary to store and grow between six and 15 eggs, causing them to bloat, laden with follicles.

“My abdomen ballooned up and I could feel something heavy inside me weighing me down,” said Barnett.

The donor is given light anesthesia for the surgery, when her doctor removes her eggs with a needle using an ultrasound.

“I was glad I went through with it but my bank account was even happier,” said Barnett, who used the funds to pay for her sorority dues and housing. Donor compensation depends on the individual agency’s policy, donor’s education, travel and if the woman is a repeat donor. The Egg Donation Program pays first time donors $7,000 to $8,000. Agencies differ on compensation for repeat donors but The Egg Donation Program adds $2,000 for each subsequent donation ($15,000 max). Therefore, Barnett —who is currently undergoing her second cycle—will cash a $10,000 check this January.

“Every donor starts looking into it for the compensation,” said Frantom. “But I’ve noticed donors start to love the feeling of helping somebody.”

Although Barnett admitted she donates her eggs because it pays well and fits in with her busy school schedule, there are some altruistic benefits.

“I’m thankful I could give someone else something so precious,” said Barnett.

It’s normal for a donor to receive heartfelt letters from her couple and become attached after grasping how she touched their lives. Some donors even feel immense attachment to their recipients, even though they almost never meet in person.

Frantom recounted a story about a donor in Northern California who agreed to donate her eggs for a loving, male gay couple. They wrote her a beautiful letter explaining how grateful they were and how much they wanted a family. However the couple’s surrogate mother didn’t get pregnant. The egg donor was devastated. Three months later the Escrow Company, which handles the agency’s money transactions, called Frantom confused, thinking they had lost the donor’s check. Frantom called the girl to see what happened. “I have it pinned up. I just can’t cash it. They (the couple’s surrogate mother) didn’t get pregnant,” said the donor.

IVF is only 20 years old, stirring up concerns about both its short and long-term health effects. Dr. David Finke, a gynecologist at Women’s Care in Beverly Hills, would recommend egg donation to his patients if they had an interest. He thinks it’s safe for women to do a few times (one to three) and would only worry about the medication negatively affecting a women’s fertility if she donated six or more times.

“The short-term side effects are similar to a bad menstrual period,” said Finke, “I would make sure to know about the possible complications before starting the process, such as hyperstimulation.” Hyperstimulation syndrome is the most common complication (33 percent of all IVF cycles according to The Center for Bioethics) resulting from overactive ovaries and causing hellish bloating in the ovaries and abdomen from excess fluids.

For some college students, egg donation is out of the question because of anticipated consequences. USC senior Paige Cooley considered egg donation but decided against it.

“I think anywhere I went, I would wonder if that was my kid. It would be too hard for me,” said Cooley.

Barnett’s future fertility is her biggest concern. “I worry that it will somehow mess me up so I can’t have kids later on, but hopefully that won’t happen.”

The process is also physically and emotionally stressful.

“You’re bursting with hormones, which can make you sensitive to little things. I started crying one day on campus when I couldn’t unlock my bike,” laughed Barnett. For some women, like Barnett, the ability to pay her expenses, while helping a family, outweighs the negative side effects.

“IVF is revolutionizing fertility,” said Finke. “It allows women to wait to have kids and gives alternative couples a chance too. At the end of the day it’s an amazing gift you give to someone else.”

When asked about her most touching case, Perchik described how she worked with a couple who lost their only child in a car accident, were unable to get pregnant again and began saving up for years to go through the process. “They called me a few days ago to tell me they are now pregnant with twins due in 2013. I felt overwhelmed, like I had a hand in setting things right…that is why I love my job…I give people their happy-ever-after.”

*Names have been changed.

Reach staff reporter Katherine Ostrowski here.