Appeal of Sanskrit Goes Beyond Religion

"Sorry?" Mooley says, glancing up. It's not him, they reassure. Mooley has been focusing on pronunciation, but the rest of the class caught on to the sentence's significance. The character is dreaming that he has a beautiful girlfriend.

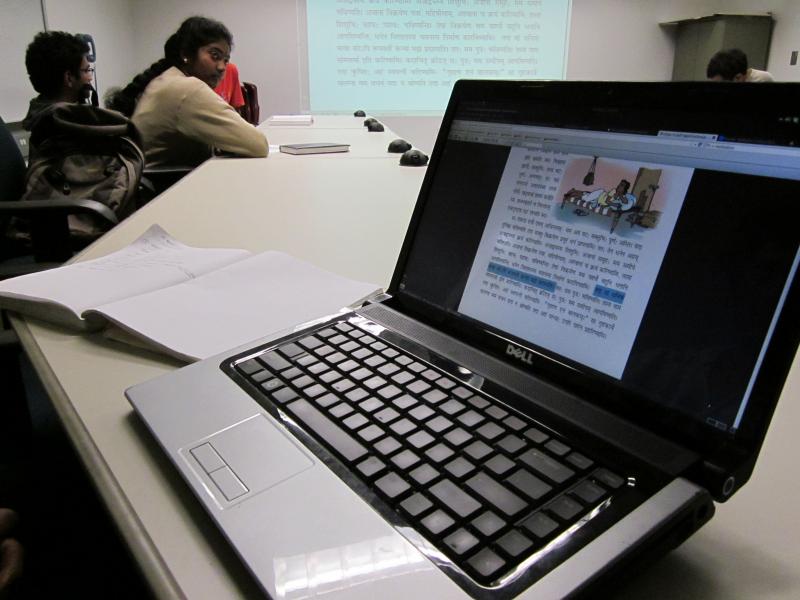

"The meaning unfolds one sentence at a time, one word at a time," Ashish Mahabal, one of the instructors, explains later. The class spends at least five minutes on each sentence, thoroughly dissecting its meaning and grammar.

Sanskrit's complexity is what fascinates this room of Indian scientists and engineers. "It's a perfectly logical and something that has been thoughtfully laid down with many rules and grammar and kind of a perfection to be achieved," Mooley, a graduate student in astronomy, says after the Tuesday night class.

For thousands of years, priest preserved Sanskrit through prayers and scripture. Today Cal Tech Sanskrit students represent the broadening appeal of the ancient and difficult language. Their interest isn't spiritual, but the study of the language itself has become like a religion, evoking a passion in its students.

Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, sacred texts dating back to 1500 B.C.E. that are the basis of Hinduism. Like Latin, a form of it was used in everyday life in antiquity, but it later became a "learned language," says Robert P. Goldman, professor of Sanskrit at the University of California at Berkeley.

"By fifth-sixth century there are not many people who speak or read Sanskrit, unless they've actually trained in it," Goldman says, explaining how it became to be associated with the caste of Brahmins or priests. But Goldman notes that poetic, scientific, and mathematical texts—"almost anything that was in the pre-modern Indian systems of knowledge"—were also written in Sanskrit. "It became the intellectual lingual franca of much of Southeast Asia."

Today, Sanskrit is taught in Indian high schools to whoever wants to learn it—Brahmin or not. "That whole concept of purity gets lost," says Mugdha Yeolekar, who majored in Sanskrit in college after learning it at her Indian high school. Contact with the lower castes made holy people, practices or objects impure.

Now a doctoral candidate in religious studies at Arizona State University, Yeolekar relies on Sanskrit in order to understand Indian culture. "In the Hindu world, it is the language of the gods," Yeolekar says. "All the religious ideas are centrally located in Sanskrit language, so if you don't know [it], then it's very difficult to study Hinduism."

Religious studies departments often offer classes in the language, but there also are a dozen programs dedicated to the study of Sanskrit in North America, Goldman estimates. He recently attended the World Sanskrit Conference, which attracted more than 1,000 participants from all around the world, though most were from India.

Outside of academia, ordinary Hindus or non-Indians into yoga culture might learn Sanskrit prayers, Goldman says. "The non-academic interest in Sanskrit is primarily from a religious point of view."

At Cal Tech, however, the Sanskrit students aren't interested in religion. "Even though I'm an atheist, I still find the Vedic literature fascinating," says Srivatsan Hulikal, a graduate student in chemical engineering who studied Sanskrit for eight years and helps teach the class. Others agree that their interest in ancient texts is cultural rather than spiritual.

The Cal Tech class is part of a network of groups at six other campuses across the United States. The Campus Samskritam network promotes Sanskrit with the help of the international organization Samskrita Bharati. It sees the language as a powerful way to unify India and secure its cultural heritage.

"It's a matter of identity for diasporic Hindus," Yeolekar says.

Using Sanskrit as a force of cultural unity necessitates offering access to the language to all Indians.

Hulikal came from an orthodox Brahmin family that still passes the Vedas from father to son. But it doesn't matter whose son you are at Cal Tech. In fact, four of the 10 in the class are women. "I greatly appreciate some of the literature in Sanskrit and I want to share it with other people," Hulikal says.

Mahabal, the other teacher and an astronomer, says to forget the past but not its language. "If you start with a preconceived notion that it's not for me or it is only for me, then that's going to decide a lot of things, but there is no reason today that that should happen."

Like Hulikal, Mahabal is an atheist with an evangelical spirit when it comes to Sanskrit. The linguistic structure fascinates him. "It's so beautiful that it entices you to get into it," he says. "Everyone who is interested…should learn this language because it's a fantastic language."

Reach reporter Megan Sweas here.

Follow Megan Sweas on Twitter.