U.S. Apology For Chinese Exclusion Act Comes Up Short

Charles Wong was among those affected by the restrictive act. It had a direct impact on his family’s history, resulting in false identities and eventually tragedy.

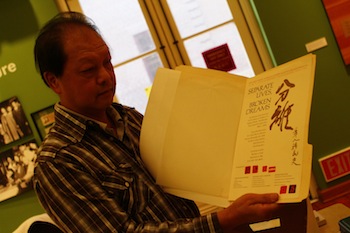

After so many years suppressing the memories of his family, Wong felt it was time to face the past and tell his story. Today, he leads the other descendants of those shut out by 1882’s Chinese Exclusion Act who are finally able to speak up.

Wong, a 63-year-old sociologist who now lives in Los Angeles, didn’t jump for joy when he heard news of the apology. He said he might have if it had come 30 years earlier. “But, finally,” he paused, taking a slow, deep breath, “I could put a closure to the saddest chapter of my family memoir.”

Wong’s was one of many families split by the U.S.’s attempt to regulate the number of Chinese immigrants entering the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act prohibited workers from entering the country for ten years under threat of imprisonment and deportation. Any Chinese citizens who left the U.S. had to obtain certifications for reentry.

As a result, Chinese men were forced to live lonely bachelor lives in the almost all-male Chinatowns while wives and children were left in China, supported by remittances sent from their loved ones in America. They rarely saw their husbands and fathers.

Wong’s family lived under the name “Leong” for more than thirty years until the government caught them in 1967. His father quickly changed the name. It was then Wong started to sense the hidden story of his family.

After his father passed away in 1985, it was left to Wong to go through his things. He noticed a suitcase he hadn’t seen before while cleaning his father’s bedroom. At the time, he had no idea that by opening the suitcase, he would uncover the truth of his family’s beginnings in the U.S.

Nestled inside the suitcase, a document detailed his father’s real life in China while working as a doctor. Wong was stunned—he hadn’t even known his father was literate.

“I thought he was just a cook for his entire life,” Wong said. His voice trembled. “I would be proud of him if I had known he was a doctor. I never showed him respect. “

Wong said he took care of his father for his entire life, as all Chinese sons were expected to do. But emotionally, they were distant. They seldom spoke to each other and never reminisced.

“Talking about family history was like a taboo,” Wong said. “No Chinese family would talk about it either because they didn’t want their kids to blab it out, or they didn’t want to face the sadness.”

Besides the papers revealing his father’s secret identity, Wong also found a picture of himself many years ago standing beside his mother and another teenage boy he didn’t recognize at first. He wracked his brain to put a name with the face. He soon realized this was the brother he had forced himself to forget. The memories flooded back.

It was 1954. Wong’s father could finally bring the family to join him in the U.S. All the family members were thrilled to reunite—it seemed their American dream was just about to come true. But when they tried to pass through interrogation in Hong Kong, immigration officers stopped his brother. They didn’t believe his story. Wong and his mother left for the U.S. while his brother stayed behind in China.

“I could remember the scene when my mom and brother cried out at the airport,” Wong said.

His mother begged his father to let her go back to Hong Kong to take care of their eldest son. But he refused, fearing she wouldn’t come back.

Four years later, his brother committed suicide at the age of 23. The family decided not to hold a public service.

“It was so miserable that I erased him from my memory,” Wong said, lowering his head. “He was like my father when we were in China. I couldn’t deal with losing him. So I suppressed that part of my memory.”

Wong pushed aside thoughts of his brother for 30 years. Meanwhile, his mother fell into a deep depression and his father continued to live a lie.

Moving on with his life, Wong earned a doctorate in sociology. His work has included examining the impact of the historically discriminatory Exclusion Act on each member of his torn family.

“See, here is the S-effects of exclusion,” he said. Wong pointed to one of the charts he drew during his work. “The ‘S’ stands for secrecy and silence for my father, separated family for my mother, and strandedness and suicide for my brother.

“But it was just one of the most typical stories of the Chinese American families affected by the Exclusion Act,” Wong said. “Most of them just didn’t talk about it any more. I just felt it was fate that made me always part of the history.”

Not many outside of the population can truly understand what Exclusion Act meant for Chinese Americans. Upon hearing about passage of the resolution, the first response of an American was typically a confused look, followed by the question, “Why is our government addicted to apology?”

Fred Ortega, the district director for Chinese American Congresswoman Judy Chu, was a sponsor for the resolution. He said the most significant part of the apology was that it reminded people of the history so similar tragedies wouldn’t happen again.

“Americans tend to have short memories, but this is an issue that cannot be forgotten because it does parallel some of the other injustices, including American history of racism,” he said. “Our issues need to be recognized and reconciled.”

The resolution included a statement of regret and respect to history, but no mention of monetary reparation.

“There is a reason for that,” Ortega said, “because compensation would make it more difficult to pass at this very point under the pressure of cutting government’s spending. “

He also pointed out too many individuals were affected. It would have been impossible to quantify or track each one of them.

Some historians considered the apology a good opportunity to educate younger Chinese Americans who didn’t know much about the Exclusion Act.

Winston Wu is the National vice president of Chinese Americans Citizen Alliance. He also led the 1882 Project, a nonpartisan grassroots effort to address Chinese Exclusion. He noticed that even families who suffered from the history didn’t discuss it. Chinese descendants are encouraged to learn business, medicine and law, which leads them into lucrative jobs while protecting them from their cultural history.

“Most of the young people, from what I know, concern only their own stuff,” Wu said, “but we have to learn from history.”

Even the mere apology took more than 100 years to finally get passed, thanks to good timing and a more active political role by prominent Asian Americans. Congresswoman Chu also recently introduced a similar resolution in the House. But she’ll need more help to get it passed.

“There are always political factors involved in the process, but we encourage young people to engage and write letters to their own congressmen,” Winston Wu said. “We hope it will be passed by Congress next year.”

Wong was happy to hear that the apology may finally be passed as a law, though he’ll be the only living member of his family to see the day.

“The apology makes all Chinese American now able to take the offensive to history,” Wong said. “Before we had to be defensive of our history. “

For Wong, what’s most important about the apology is that those affected can now legitimize their family history.

“You don’t have to go to the denial, you don’t have to go through the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell.' Now you can put it out there—finally, finally.”

Reach Contributor Corrina Liu Shuang here.

Best way to find more great content from Neon Tommy?

Or join our email list below to enjoy Neon Tommy News Alerts.