Stripping Naked

With subjects ranging from a pigeon feather to men’s boxer shorts, from a Ferrari to a Boeing 757, Veasey’s work transports the viewer into a parallel universe, a place where the most mundane of objects are stripped of their external embellishments and hidden reality and inner beauty revealed.

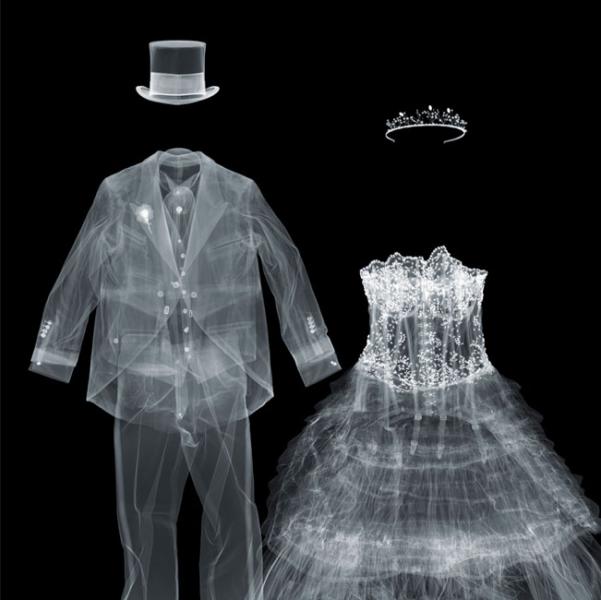

“We all know we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, that beauty is more than skin deep,” says Nick, as he likes to be called. Case in point, while most photographers would crave to photograph Adriana Lima in a Vera Wang wedding dress, the Londoner chooses to picture the same wedding dress under the probing eye of an X-ray. What he uncovers is the construction, sewing and layering of the fabric that underlies the external elegance of the gown’s form.

Interestingly, Veasey did not take his first X-ray photograph to appreciate inner beauty. Rather, desperate to win a £100,000 promotional prize from Pepsi, Veasey convinced his then-girlfriend’s father, a radiologist, to let him X-ray thousands of Pepsi cans (from the Pepsi truck he was driving) to find the can with the pull-cap of a different metal. Though he never found the prized can, the images “sparked off the ideas” that have defined his career.

Almost a hundred years before Veasey had his AHA moment, Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen was working to study the properties of beams of electrons, the negatively charges particles that revolve around the nucleus of an atom. Late on a chilly winter night, he noticed a film glowing unexpectedly across the room during his experiment. In an effort to save the precious film, he placed a piece of cardboard first, and then, a metal box between the cathode tube and the film. But to no avail. Invisible radiation could pass through these obstacles to strike the film. Not knowing their source he called them X-rays, a name that have survived since.

To explain why he was missing dinners at home, Rontgen invited his wife, Anna Bertha, to the lab, placed her hand on a film and exposed it to X-rays. What happened next, changed the face of modern science and medicine. The developed film shocked Anna, “I have seen my death!” She could see her bones. It was the birth of X-ray use for medicine.

Just as gravity drives water from higher to lower altitude, potential difference drives electrons from the negative to the positive electrode in an X-ray machine. But their path is not clear. On their way, the high-speed electrons strike tungsten filaments and lose energy. Some are slowed down by the pull of the atom’s nucleus (positively charged). Others knock out electrons from the electron rich-tungsten atoms. The energy lost is emitted out as X-rays.

Using modified versions of Rontgen’s setup, Veasey produces his work at his studio in Kent, England. While at a reception for his latest work at the Glass Garage Fine Art Gallery in West Hollywood, I take a virtual tour of his studio. As Nick navigates his laptop through his workspace, I see large black and yellow radiation signs lining the industrial insides of his studio look intimidating.

As Veasey prepares a demonstration of his work, he places a purse “with a secret” on the lead floor and shows his viewers the control center in the adjacent room.

Danger is real, informs the Brit. Having accidently suffered heavy radiation exposure twice, Veasey now walks around his studio with a radiation monitor.

So potentially harmful are X-rays to living tissue that medical exposure for patients lasts a fraction of a second. Veasey’s subjects however require exposure for minutes at a time. Here too, Rontgen’s work comes to Veasey’s aid.

Not only did Rontgen discover X-rays, he also discovered that lead blocks are only substance impenetrable to these invisible. No wonder Veasey’s studio has lead floors, lead doors and lead walls to shield himself and his neighbors from the deleterious effects of X-rays.

“He doesn’t involve his assistants in this part of his process,” said Wendy, his assistant of four years, who has yet to see the insides of his studio.

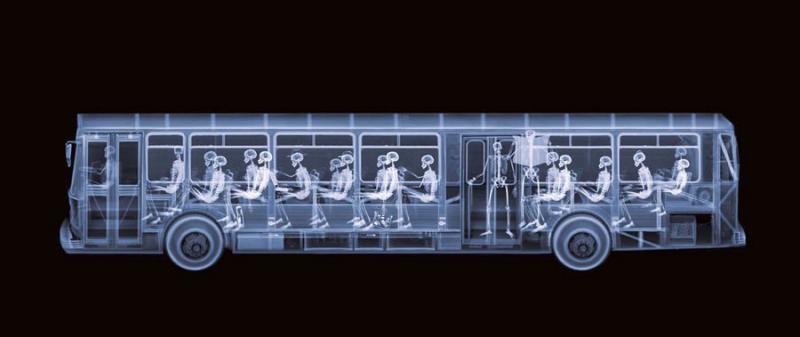

While X-rays images are all black and white, with Adobe Photoshop by his side, Veasey infuses color into his X-ray images to give them an ethereal hue, an effect best seen in the picture of a shirt he photographed. The crisp lines defining the creases of the shirt, almost appear like careful blue brush strokes.

In his quest to capture the “soul” of his subjects, London-born Veasey has worked with a lot of subjects, some more aesthetically pleasing than others. At the bottom of the list are human cadavers. “[They] don’t smell great and scare the hell out of me, but how else can I get an image of the human form without exposing a living person to radiation,” explains Veasey.

Indeed, cadavers are an integral part of the 49-year-old Briton’s latest exhibition, titled ‘Patriots Acts.’ The $14,500 center-piece of the collection, called “Airplane in the Hangar” took Veasey three months and three cadavers, to create a composite snapshot of an airplane being serviced.

Veasey’s work is designed to “provoke thought” about the invasiveness of technology in our everyday lives, from the use of X-rays in exploration, surveillance, security and espionage.

Veasey’s current collection is a “prime example of post 9/11 artwork,” says Henry Lien, director of the Glass Garage Fine Art Gallery in West Hollywood.

The final product is a limited edition Veasey print with no more than five copies floating around in the world. Though images of his work are available online, it is his prints that have won him numerous international accolades.

Having conquered the inanimate world, Veasey now has his sights set on the biological world. Drawing inspiration from Anna Atkins, the 19th century photographer, Veasey is adapting her technique of using sunlight to develop film to explore the delicacy of the world of seaweeds using X-rays.

Back in his studio, Veasey steps out of the dark room with a developed film. I see the purse’s “hidden” truth. It’s a vibrator!

Best way to find more great content from Neon Tommy?

Or join our email list below to enjoy the weekly Neon Tommy News Highlights.