What's There For You When You Feel Like You're Underground (USC Chronicles)

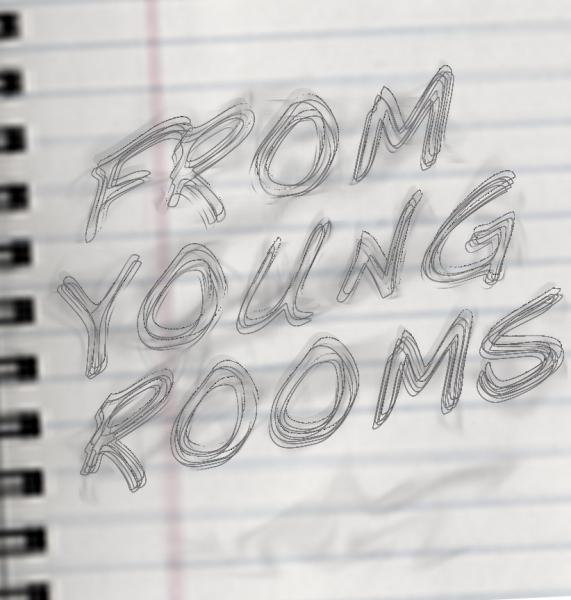

Editor's Note: "What's There For You When You Feel Like You're Underground (USC Chronicles)" is part of Michael Juliani's poetic series, "From Young Rooms."

They act like everything is in the way of socializing. It’s all “shit I have to do.”

A slow Friday night means they’re near death.

Enter a room and see them in sweatpants and basketball shorts slouched on the couch cuddling each other’s feet. The television plays a usual medley. Food bags on the “coffee table” with folded-over schoolbooks.

I wake up and fill my time waiting for lunch. The only place I don’t shower in the mornings is my childhood home—the red bed, the blue carpet, the stickers, and books. I’ve let my face grow hair for a week. Everyone says that women don’t like beards.

When you’re with them, people feel, in a way, beyond criticism. Their facts mute your critical tick. Their inadequacies are just what they are. They get up to the fridge asking if you want a beer and you say, “Sure, might as well have one too.”

The land of opportunity, or just blank space, static, tiding over. Buildings. We make it our own way. Some wake up and run the track in the mornings. Some take the train home for weekends. Some miss whole weeks of class. Sleeping in till noon. Yelling at the RA in the middle of the night to fill the condom bucket, drunk running down the hall shirtless, pants undone in desperate need of one—(“Hey, dammit, this is your one important job!”). Still stoned in the morning shower. Trying to trace any tracks of possibility in the attractions he’s talking to.

People do these things, all in one life so far. For four years owning a city but feeling tied within it. On the brink of some fantastic action. The most beautiful people in the world come one after another into the dining halls. Money is a theory, unless you work. They line themselves up with the currency of potential, or just mess around.

Sometimes help doesn’t come because of the lack of understanding, the disconnect, or the violent need to remain hidden until found.

(Weekend): A girl we know cries on the sidewalk in front of the apartments in a dress. Her boyfriend rocks back and forth on his Kenneth Cole heels in a red bowtie looking at the sky and breathing, opening and shutting his eyes as if gaining courage. She has a styrofoam cup with the lid taken off and red ice webs out on Figueroa at her feet like entrails slowly turning to a puddle. We’d like to keep moving, but Richard has his arm wrapped around her neck, speaking softly above whisper in her face, “We love you…we love you…”

The cleaning lady had come into the rec room while I was playing ping pong with guys and blowing my nose in a wrinkled tissue buried in the pocket of my pants. “No beer—No beer,” she said, short and stout, not too old, talking as if to old liars. “I see on cam-er-ra—Can have no beer—“ We move to put the cans, four or five, from the floor and table into the trash. I wonder if we’re supposed to leave. “Qué hora es?” --“Nine-thirty,” Ben says. “No Inglés.” His eyes move to the ceiling like he’s calculating numbers. “Nueve y media—“ “Ok…puede jugar, pero no can have beer.” I serve from steps back from the table to start another loping rally. “Ok, sorry, gracias. Don’t worry, no more beer.”

(Bathroom): He uses the smaller of two urinals when he has a choice, a German-looking goatee, light brown. He brushes his teeth in the long mirror. The porcelain reflects into it without shine. Dark green, brown clothes—a wheeled suitcase, black, heavy like a dog or a small child he’s holding hands with. He glances at me sidelong in the mirror. Our eyes meet in the slant, the only way you can see someone without seeing the real thing when he’s in the same room as you. I adjust my pants by lifting the buckle of my belt. Wash my hands—water, no soap. He dries his hands methodically, completely, with an arrogant patience. The face an artist makes fixing a mistake.

Once he leaves I go to the door, beginning to open it, seeing the empty hall. No footsteps, just doors opening and closing to classrooms breezing with soft discussion. I go back to take my turn, at the taller one, spitting into the small bowl. I had come just to blow my nose. Our professor tells the six of us in Friday morning class that we may get up and out at any time for any personal reason. In the middle of the first obvious (or excusable) point, I rolled away from the table and moved to the door looking at the clock on the wall.

(If You Don’t Get Married She’s Gonna Break Your Heart, Son): His hand holding her elbow on the bench in Alumni Park beneath trees, in the shade, tucked in the middle of campus but away. Guiding her this way. You put grass somewhere and only lovers and loners come to stay. She kisses him behind the ear and rubs his back, looking behind him from the side. The squirrels lunge and dig. His bags on the bench packing them in together so no one else can sit down. His glasses up on his hair. Her purse rubbing against her hip on the end, out of sight. Her bare legs crossed at the ankles. Her leaning into him. His bicycle tied to the arm where his body presses into cold metal.

(Elevator): --“Third floor.” --“Good, me too.” The person slips out once we reach the top. I’m transfixed flipping through pages of something I bought that arrived in the mail. The elevator door closes, steel. The cab doesn’t move. I don’t notice for another minute, waiting for it to keep going up.

(Normal Stranger): --“Hey guy, you a student here? Mind if I sit down? Nice day, you smiling, t-shirt, reading book. Why not read book on meditation, intercellular, breathing…” (thick Eastern European accent, like talking with mouthful of chocolate—bald head except for a ponytail, pale, strap sandals, the book with a cover that looks like a Scientologist’s uterine-shaped diagram of bright stars). --“Nah, that’s okay man.” (He looks for a beat.) --“Nah, really, that’s okay man. Thanks. Sorry.”

(New Folks): My sleep, more often than not, is a deadened trauma, like a broken television’s cracked crackle. This was two years ago. One of the first parties I can go to but I wasn’t invited. Word spread through a friend who was a friend of the friends of the birthday girl. We walk there up Figueroa past the bar—its entrance blowing light through the slit in the curtain and onto the bouncer in a black collared shirt with his arms folded, the stitching “SECURITY” over his breast. There’s the car dealership the school wants to buy and tear down but can’t because the city somehow considers it a historic monument. Half the kids walking with us I’ve never even heard of before. They’re all from Canada and live in the hotel on the floor beneath us or one lower.

Women’s volleyball players ride their bikes up to the stoplight, legs bare long in spandex in the relative cold. One who’s six-foot-four pushes her hand against the light pole to lean from beneath the curb in the right turn lane. Her eyes are the most striking olive, and chestnut brown hair—she looks like the whole world is a swamp that she owns. Like Cleopatra. A Canadian starts talking to her. She smiles through the exchange smooth like she’s destined to pat him on the cheek and go home.

Our party groans right across the street from the volleyball apartment. The giraffe-like legs stilted for the stairs. The birthday girl lifts a handle of vodka and drinks until her friends reach the chanted number 19. A girl in the doorway to the open ground-floor apartment goes on her tiptoes to kiss a shirtless man much taller than her with muscles and tattoos on his ribs. She’s in a bikini top and jeans shorts frayed, no shoes.

Cheap streamers from the dollar store line the canopy between the second-floor balconies. The table of booze and cups set up in the middle. She’d probably been sleeping there with him all weekend. They share a cigarette, passing it with its tip pointed down, blowing out the smoke while waiting for the other to take it. The moon looks like a wolf. We start tossing the football. The Canadians don’t know how to play.

(Pills): “No it’s okay, Officer. These are just Sudafed. I promise.”

("Lost in a Roman wilderness of pain"): I take three Advil with tilted sips from the bathroom faucet. I take two more big sips to wash them down. In the morning you hear the outside traffic on Jefferson whooshing and swaying through the open windows of the living room like hearing the ocean in a seashell with your razor burn from the night before and nose a bit full gleaming pale lime in the tissues tossed into a plastic bag on the nightstand. Last night the urbanity of our certain darkened and desert chilled streets had litters of couples going to dinner and then out to their formal events. That was how we found that girl crying. In our lives, the prom never ends. The standard of dress length keeps shortening. As groups pass, every male head on the street turns to watch the young women go, in pink, in black, the hips of the dresses cut out on some, the straining ripple of calves. The same way their mothers dress at church.

When I went to a couple of these last year the line to the men’s bathroom was always poorly thought out and then ultimately ignored. “Just piss in the sink!” they yelled, gaining support from the end of the line, such as it was. The forcefulness bred nerves that made it impossible to go. At the urinal a wall of men would be behind you, egging you on to hurry up.

They’d bus us out to fancy restaurants without telling where we were headed. The girls sang dirty songs, slapping the sides of the school bus roof. They pulled their hems down as they stood on top of the seats. Drunk couples invaded the space of the sober ones behind them, tongues touching, their heads pushed back out of intensity. It was the circus of the prosaic. The people there had great internships. Mandatory study hours, Monday night dinners, the songs themselves.

Closing the living room windows is noisy. It makes a smudge sound from the scrape. My friend Cole filled a red cup with tap water for our walk home after he’d had just one beer. “If a cop stops me thinking it’s beer I’m gonna toss it in his face and say ‘It’s just water you fucking cop! Ha-ha!’” He immediately went back to the look of grinning dark focus we think means he’s having a moment away.

He put one hand in his pocket and swirled his cup over the sink like wine or whiskey & Coke. His clothes rendered a pained dust—the web of skin connecting his thumb to the rest of his hand is branded with the smallest facsimile of the bull, Taurus. (“If you look at it long it just starts seeming like a fat girl on all four stick legs with a whip for a tail. Either way I’m cool with it.”)

By the time we’d reached the street in the new night wind he’d sucked down the water, bottle bent out of shape, and began wheeling around for a trashcan, biting his lip as he whirled. “Look right and look left, you’ll never find one. It’s straight ahead, you dummy,” I said. The waffled metal can right on the curb. Its plastic bag fluttered from the movement of the cars and city buses of lights that hugged the line, rushing hot and odorous air onto the sidewalk. Cole moved to go throw his cup away. He stopped when a herd of high heels and suits passed in front of him. He turned to look at the girls.

(Talking Into Glass/Trying To Be Perfect): I learned the other day from someone that USC has a very large transgender population.

“I saw an episode on that on Oprah once. Even though I’m gay I still have a hard time understanding it,” Richard says. “Well yeah, transgender issues are gender issues. They have little to do with sexuality. Chaz Bono, dude.”

“I saw something on it on Tyra once,” Ben says.

We’re crossing a street, the numbers counting down next to a flashing red hand. They’re going on to a party. I’m going home.

People sit in circles in tailgate chairs with cup holders, drinking beer cans and smoking cigarettes and cigars in the courtyards of their apartment housing compounds it seems in preparation for the game tomorrow night against Utah. I can hear someone flicking heavily into the empty dent of a can. Loud laughing and conversation, but not entirely wild. Then again we’re removed a bit on the uneven road.

I get home to the empty unlit third floor apartment I like to come home to and flick on the kitchen lights to reveal pots and pans in the sink washed full with water. That walk alone, the last bit by the black church and reeds, makes me try to place myself. I’m “in college,” I think. It’s the American moment that’s so different than stories and yet not different at all.

Everything you’d expect to find is here, depending on how willing you are. The experience is what drifts you. Even after your thinking so hard, it starts to paint itself.

The keys and wallet and phone go onto the desk. I step into the shower and remember nights, 18 years old, sitting in the tub getting sprayed by the head, my roommate’s small radio playing on the sink, a can in my hand along the rim sprinkled slowly filling with water.

“Mike, what are you doing, man?”

“I’m taking a bath.”