The 3D Printing Revolution in SoCal

Slowly and rhythmically, a nozzle squirted melted plastic onto a small rectangular platform below it, forming a cross-hatch pattern. Then, suddenly, something went awry with the machine.

Gilmer hit a button on his computer, which was wired to the Cupcake, and the machine died again.

“Sometimes it doesn’t work,” said Gilmer of 3D printing, the manufacturing trend that’s becoming wildly popular with tech hobbyists and designers. “But when it works, you have the time of your life.”

Crash Space represents only a tiny microcosm of the 3D printing world, a relatively new field that allows people to print life-size, tangible objects from a computer program, just as one would print a term paper from Microsoft Word. Although the technology has only been around since the ‘90s, the 3D printer has already revolutionized fields like architecture, industrial design and entertainment, growing into a $1 billion market annually by allowing its users to mint exact replicas of objects straight from computer drawings. With 3D printing, made-to-order models of sci-fi movie costumes, for example, can be made in just a few days, as opposed to a few weeks with more traditional types of prototyping. Designers no longer have to comb the market for parts that suit their needs. They hit a button and make it from scratch.

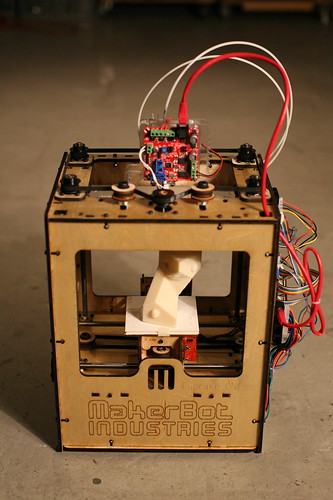

Because the machines can cost anywhere from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars, 3D printers have largely only available to large firms or institutions. But a few years ago, consumer printers like the Cupcake entered the market, sparking a host of possibilities for the layman - which futurists like those at Crash Space are eager to enumerate:

By making their own products at home, people with great design ideas but no access to manufacturing equipment could start businesses. Pollution and costs from transporting consumer goods could be drastically cut. Americans could finally bring back the phrase “Made in the U.S.A.” - all from their very own living rooms.

***

Crash Space isn’t solely dedicated to 3D printing - it’s a collective of technology enthusiasts who meet semi-regularly to work on various music, industrial and tech projects. (It’s a “nerd clubhouse” as one member, Vance Gloster, explains).

Several of the Crash Space members own the Cupcake machine, which is one of the only consumer 3D printers on the market. They meet on weekends to design and print objects together, both because it’s more fun that way, and because, more often than not, the machines need a little collaborative tech-support.

“Like most geeks, I love technology that inspires me to think about the future,” Gloster said. “But I wouldn’t recommend my friends go out and buy one right now, because I’d spend three weekends out of the month helping them with it.”

That’s because the Cupcake, like other printers made by the Brooklyn-based company Makerbot, is assembled by the person who buys it, and it consists of many delicate moving parts. Like all 3D printing, a Cupcake creation starts when a person makes a design in a drawing program. (Though the computer aspect may scare off technophobes, those with no computer expertise or drawing skills have said that they mastered the program within a few days.) The design is then inputted into another program that controls the machine’s printing pattern. The inside of the printer holds a tube of plastic called ABS, the same material used to make Legos. Two resistors heat up the ABS, and a nozzle squirts it onto the platform - like a frosting bag frosting a cupcake – which is how this particular model got its name.

A few minutes later, a custom-designed plastic widget is formed.

Some Crash Space users have made replacement dishwasher parts, thimbles or cases for electronics equipment. Although they occasionally gripe about the technology’s quirks, they hope that as 3D printing develops they’ll be able to print bigger, better things that can’t be bought elsewhere.

Like many others in the 3D printing movement, Trowbridge sees a new era in manufacturing coming within just a few years.

“Today we download music, but pretty soon we’ll be download products,” Trowbridge said. “It’s the industrial revolution 2.0.”

***

Not all 3D printers are as compact as the Cupcake. The technology began several decades ago with vast machines the size of small cars, many of which are still in use today. However, their high price relegated their use to only the labs and large corporations that could afford one.

That is until spring of 2009, when Makerbot created and released the Cupcake. It retailed for $750.

“We were driven by the fact that we were cheap, but we really wanted a 3D printer,” said Bre Pettis, one of the Makerbot founders.

A former schoolteacher and lifetime “tinkerer,” Pettis said he and a group of friends designed the first Cupcakes through “brute force and trial and error,” which also seems to be the M.O. of most 3D-print enthusiasts.

“Our users are a mix of tinkerers, engineers and ordinary people who want to live in the future,” Pettis said. “The ‘ordinary people’ segment is growing like crazy.”

Over the past two years, Makerbot has grown from five people to 29. Pettis said there are now about 4,000 Makerbot printers “in the wild.”

The company has also more recently released its Thing-O-Matic printer, which makes improvements on the Cupcake and allows for more accurate printing.

The technology has gotten so popular that there are now even massive Web sites devoted to the creating and sharing of 3D designs: Thingiverse.com allows its members to upload and download the design files, while Shapeways.com offers 3D printing services for people who have their own designs.

Pettis said he already prints most of the household items he needs, including desk supplies and a dimmer switch for his kitchen light. He said that once someone gets a Makerbot, they get “3D printing goggles.”

“You look at the world, and if it's less than 12 by 12 by 12 [centimeters], you'll just print it,” he said.

***

The mission of organizations like Crash Space and Makerbot is, for the time being, largely hobbyist. But for years now, researchers, designers and architects have also been using 3D printing for practical, real-world applications.

Tom Wiscombe is a Los Angeles architect who realized a few years ago that the architectural models he relies on could be more efficiently made with a 3D printer. To pay for it, he started a 3D printing business on the side of his architecture firm.

“I wanted to build more models in my office, but we didn't have a way to do it here,” he said. “We decided to pay for the machines and maintenance by creating a second business, Crystalline.

Wiscombe has the Eden 3D printer, a $100,000 model that can handle bigger jobs with more precision. Ever since he started 3D printing, Wiscombe has found, to his surprise, that another major L.A. industry is also in dire need of rapid manufacturing: show business.

“I thought I’d be doing work for my architect friends, but it's mostly Hollywood work that we do here,” he said. “I do a lot of science-fiction stuff.”

Like other industries, movie studios are increasingly finding it too slow and cumbersome to create dummy prototypes of props, wait weeks for them to be created, make changes, send them back and wait for the real thing. Instead, filmmakers for movies like “Spiderman 4” come to Wiscombe in order to print out the actual models for costume parts that will be used in the film.

“It’s the best and fastest way to get models,” Wiscombe said. “It’s the magic of coming in in the morning and having the finished product there - like baking cookies.”

The technology can also allow researchers to create highly specialized objects that don’t exist on the mass market. Dr. Robert Rennaker, a neuroscience professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, tests animal responses to certain odors by using devices known as “nose-pokes,” which allow an animal to choose one of two answers by poking a sensor with its nose. Because of the niche nature of his field, Rennaker makes his own parts using a 3D printer. He's currently designing a 3D-printed wand that will be used to stimulate different parts of the skin in order to treat phantom limb pain.

"What used to take me four or five months to make now takes me a week," Rennaker said. "This thing is just awesome."

It’s easy to extrapolate how far 3D printing could go as it develops. Last November, a Canadian company called Kor Ecologic created Urbee, the world's first 3D-printed car. Just this month, New York City-based French Culinary Institute teamed with the computational synthesis laboratory at Cornell University to make 3D-printed snacks using pureed food instead of plastic.

In 2010, Italian architect Enrico Dini built the first-ever 3D-printed building using a printer the size of a shed. (His upcoming idea is equally as colossal: "What I really want to do is to use the machine to complete the Sagrada Familia," he was quoted as telling Blueprint Magazine.)

***

At their most ambitious, the Crash Space guys in Culver City predict a day when American consumers can make anything and everything they could ever want. They point to a “Star Trek” episode in which, “Captain Picard walks up to his replicator machine and says, ‘Tea, Earl Grey, hot,’ and the replicator makes it for him," one Crash Space guy explained. "The future of 3D printing is like that."

But there’s a ways to go before we can all print our own T.V.s or Priuses - or teas, for that matter. For one thing, most industrial-grade printers are still far too expensive for the average person. And while Makerbot's machines are affordable, they are not without their kinks, like the fact that some shapes simply can't be printed out very well from a nozzle.

What’s more, Makerbot products don't currently work with metal, the key ingredient needed to make circuits and other innards for consumer electronics. Pettis, the Makerbot founder, assured me that his research department is "obsessed" with getting the printers to work with metal. Until that happens, makers like those at Crash Space are limited to small items that can be fashioned out of plastic.

"But if we could make things with metal, we could take over the world," Trowbridge said.

Until that day comes, they'll just have to be satisfied with ruling the Thingiverse.