Whittier's Oil Drilling Plans Face Environmentalist Opposition

How does a city with a looming budget deficit put itself back in the black? The Whittier City Council thinks it might have found an answer: drill for black gold. The idea has been thrown around for three years in the modestly-sized city, and the only thing to come up so far is hot air, as opposition has slowed the project.

Environmental and neighborhood groups have recently put the project’s environmental impact report into revision and issued a lawsuit to stop the project in January.

When the final EIR is ready – likely April or May - it will arrive at the city’s planning commission, which will make a recommendation to the city council. At that time, the council will cast the deciding vote on whether to drill in the Whittier Hills – a current nature preserve.

As a drive past the nodding donkeys on La Cienega Blvd. will show, oil drilling is far from a novel concept in Los Angeles County. To this day, cities from Beverly Hills to Santa Fe Springs bring in revenue from oil extraction taxes. Beverly Hills accrues an estimated $1 million per year from oil and natural gas extraction fees.

But Whittier is different from these other oil-producing cities. In Beverly Hills, for instance, many of the mineral rights – and royalties - belong to private entities, such as the Huntington Library and Art Galleries in San Marino in one odd case. In the case of Whittier, the city stakes a claim to 100% of the mineral rights in the hills. Instead of levying an extraction tax, the city stands to gain a 30% royalty on all oil revenues. The deal was negotiated with Santa Barbara-based Matrix Oil Corporation, who won the bid to drill.

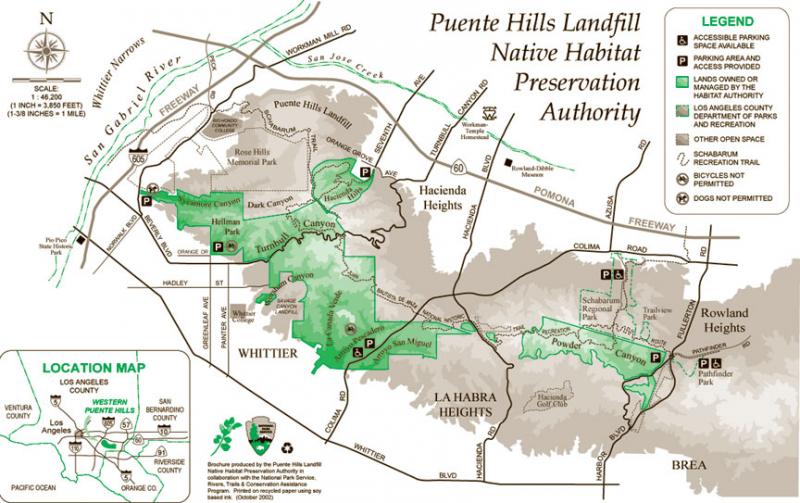

And taking a position that has surprised some local environmentalists, Bob Henderson, the councilman credited with turning the Whittier Hills in to a preserve in 1994, is also leading the charge to explore drilling. Henderson is chairman of both the Puente Hills Landfill Native Habitat Preservation Authority and the Whittier/Puente Hills Conservation Authority.

He estimates a minimum of $8 to $9 million of revenue for the city per year from drilling.

“It’s been an oil town for 100 years. We always thought of ourselves as an oil community, and that’s part of the reason the city was successful. We may decide it’s not worth doing but I’d feel negligent to the citizens not to look in to the asset,” Henderson said.

Mike McCaskey, vice president of Matrix Oil, said that revenues could reach ten times Henderson’s estimate. The company will target a thousand barrels of oil per day for a period as long as 30 to 40 years, totaling up to 60 million barrels. Crude is currently selling for upwards of $100 per barrel.

Whittier has seen many of its car dealerships, a primary source of sales tax revenue to the city, close up over the past two years.

“Cities and LA County are cutting services. This is a way for a community to rely on its own resources,” McCaskey said.

But some claim the city can’t legally profit from drilling, because Henderson purchased the Puente Hills Landfill Native Habitat Preservation for the city by spending countywide tax dollars. Henderson bought the 1,290 acres of parkland, along with the mineral rights to Canada Canyon in 1994, under Proposition A.

The proposition, a 1992 ballot measure, funds preservation of open space countywide and costs the average Los Angeles County taxpayer a little under twenty dollars per year. The non-profit group Open Space Legal Defense Fund sued in January, claiming the drilling plans were misappropriating county funds and betraying the intent of Proposition A.

Councilman Henderson said that Proposition A provides a clause for changing land use, while others disagree. “City council has taken its own interpretation of the proposition,” said Roy McKee, vice president of non-profit advocacy group Whittier Hills Oil Watch.

Oil production in Whittier is far from taboo. Chevron Corp. operated wells in the Whittier hills until 1992, when oil bottomed-out around $14 per barrel. By the mid-nineties, many multi-national oil companies, including Shell Oil Co., had packed up operations from Southern California due to low revenues.

But as these worldwide players like Chevron and Shell packed their bags from the region, Matrix moved in to Whittier in 2001. The company now operates 25 active oil wells in Whittier’s Honolulu Terrace and Sycamore Canyon. The Honolulu terrace site became national news in 2005 when a rig exploded, killing one worker. The incident remains a talking point for opposition concerned for the community’s safety.

In 2008, the city solicited bids from oil companies for a 30 year lease to resume drilling in the hills and Matrix Oil Co. won the contract. The small oil company paid 25 percent of the lease. Texas-based Clayton Williams Energy Inc.., which specializes in oil exploration, put up the remaining 75 percent. Anti-drilling advocates cried called foul on bringing big oil back to town, but plans continued.

In January 2011, a Los Angeles superior court judge allowed the Open Space Legal Defense lawsuit – predicated on Proposition A - to proceed. The non-profit group’s legal defense is supported by the larger non-profit Whittier Hills Oil Watch, which has gathered some 5,000 signatures from the city of roughly 83,000. At a series of recent fundraisers for the lawsuit, opponents have continued to voice concerns.

Health concerns include the potential for contamination of the city’s aquifer and the potential for inhalation of toxic fumes such as benzene, which accompanies oil spills. A school for developmentally challenged children sits 1500 feet from the proposed site.

“By the time we see the damage it will be too late,” said McKee of the Whittier Hills Oil Watch.

Many of the opponents live in the immediate area surrounding the hills, and worry falling property values and the possibility of further depressing an already struggling housing market.

Lori Frear, 53, was born in Whittier and aspired to live near the hills from an early age. She bought a house adjacent to them in 1997, during a lapse in the drilling.

“I didn’t buy near the hills to be near industry,” Frear said. “I think it would be a deterrent to someone looking to buy now. The drilling’s too risky, and with the noise and the traffic I don’t think it will enhance the community at all.”

A 2010 study by Los Angeles-based AECOM Technical Services states houses closest to oil operations could expect a fall in value of approximately 10 percent, and “a couple individuals also suggested that these same homes typically took twice as long to sell.” The study was based largely on interviews with local real estate brokers.

Some environmentalists believe that if drilling is allowed to proceed, it could re-open oil wells around the state, as there would be no precedent to stop other cities from mining for resources in their own parks purchased with similar funds. There is roughly $1 billion of Proposition A parkland in Los Angeles County.

Ernie Diaz, president of Open Space Legal Defense Fund, envisions the present lawsuit reaching the California State Supreme Court, and hopes anti-drilling legislation is developed from the case.

Opponents also cite the lack of restrictions on future projects and wells in the Whittier Hills. The lease to Matrix Oil stipulates that after the initial wells have been drilled, the oil company can apply for additional permits from the city.

“The lease allows Matrix to develop all 1290 acres,” said Whittier Hill Oil Watch spokeswoman Paula Valle.

Councilman Henderson said that the project would be invisible and inaudible for Whittier residents, even those hiking in the park, and would occupy no more than seven surface acres.

The park is also home to coyotes, rattlesnakes, bobcats, toads, scorpions and tarantulas. Local resident Lupe Sahagun, who hikes in the park weekly, has said that wildlife has visibly improved since 1992.

“The hills have recovered. They’re pretty, but you can still see the scarring and land movement,” Sahagun said. “That’s what happens when greed overtakes everything.”

Reach reporter Jonathan Polakoff here.