Mohammed Nabbous: Libya's Independent Journalist Martyred

Libya Al Hurra TV is the creation of Mohammed Nabbous, a 28-year-old Benghazi resident. He started the station at the beginning of the pro-democracy protests that spread across Libya in the past few weeks. What began as a broadcast of a street in now-liberated Benghazi was being hailed by fellow journalists like NPR’s Andy Carvin as Libya’s first independent news station.

On this particular night, a Saturday, more than 2,000 other viewers were tuning into Nabbous’ fledgling station. Though it was a late night for most-- 3 a.m. for my family and I-- Nabbous had promised us fresh footage from Benghazi that would prove that Gaddafi’s regime was not complying to the ceasefire they promised. The declaration came after the U.N. passed a resolution that approved the enforcement of a no-fly zone if Gaddafi continued to use aggressive force against citizens.

“He is bombing Benghazi, no doubt,” Nabbous breathlessly told us before introducing the videos. In just hours, he would be dead.

I had never met Nabbous, but I felt like I knew him-- most of his viewers felt the same way. We referred to him as Mo and spoke about him not as if he were a stranger we knew only through a window on our computer screens but as if he were a close life-long friend. He had become a beacon for the Libyan community abroad, an impalpable tether to our family and friends back home in Benghazi.

At an early time when there was little to no media coverage of the Libya clashes, Nabbous was the only one reporting from inside Libya. When communications in Libya were down, and family abroad couldn’t get ahold of loved ones inside, Nabbous allowed viewers to send in their phone numbers. On air, he would call family members himself and make sure they were safe. He and his wife Perditta worked around the clock to bring amateur footage of clashes and proof of the violent force being used against citizens by the Gaddafi administration.

That night, Nabbous’ footage was particularly damning. It was taken in Hay Al-Dollar, a neighborhood southwest of Benghazi, where a rocket launched by Gaddafi forces had crashed into a house. The rocket had struck the room of a 9-year-old boy and an 11-year-old girl, both of whom sustained injuries from the shrapnel. Nabbous’ filmed the ruins of their home and, chillingly, the childrens’ pillows, now stained with blood.

The video was compelling, but it was not what I-- or any of the people watching that night-- would remember the most. Instead, we would remember what happened right after.

The video was replaced with a still photo and we were left in silence for a few minutes before we heard Nabbous‘ voice again.

“I’m in the back of a pick-up,” he explained from his cell phone.

“We are bombed right here in front of us,” he told us calmly over the din of loud blasts and gunshots.

From my house in Southern California, my family and I listened intently to the cavalcade of sound-- we couldn’t distinguish the clamoring noises of the truck from the blasts of what we believed to be bombs.

“We are actually inside where they’re shooting right now,” he said. But he was distracted. The last thing we heard him say before the call was cut was a warning for his friend to “go back!” And then silence.

Nabbous was shot, but we only heard rumors of it until the next day. I woke up to find my mother’s face wet with tears. “Istashhad,” she said, “He was martyred.”

That Saturday, Nabbous was one of 94 Libyans who died at the hands of Gaddafi forces. My cousin Hamadi Herwees was another one of them.

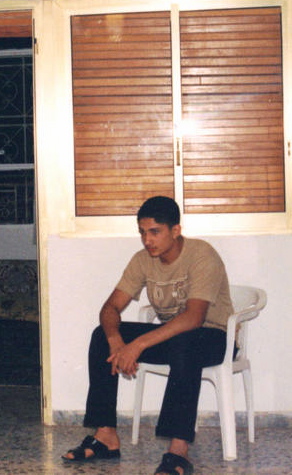

A few years younger than Nabbous, Hamadi (pictured on the right) was just one of the hundreds of thousands of disaffected Libyan youth who felt cheated out of a brighter future by the Gaddafi regime.

For years, they have heard fables about Libya’s massive oil wealth of which they have seen nothing. They have rubbed the bent backs of their parents, who worked dangerous jobs and received pennies for it. They watched as Gaddafi silenced dissident voices with public hangings and life-long imprisonments; robbed women of their fathers and husbands in massacres the regime tried to sweep under the rug.

Empowered not by anger but by a deep sense of injustice, the youth took to the streets and liberated Benghazi from the shackles of this tyrannical regime. But no revolution is without its losses.

Hamadi, like Mohammed Nabbous, was unarmed when they shot him.

The world has dubbed these people “rebels”. Who are the Libyan rebels? questioned the headlines of several articles. Are they Al Qaeda? Are they Islamists? Who are these children wielding guns like toys, these men straddling tanks like horses?

And I wish I could answer: they are Mohamed Nabbous. They are Hamadi Herwees. They are Iman Al Obeidi. They are young children and old men; women and teenagers.

They are teachers and doctors; architects and engineers.

They are journalists and story-tellers. I call them family. I call them friends.

You can call them revolutionaries.

Reach reporter Tasbeeh Herwees here.

Sign up for our weekly email newsletter.