Columbine Family Finds Beauty In Ashes

Comments (11)

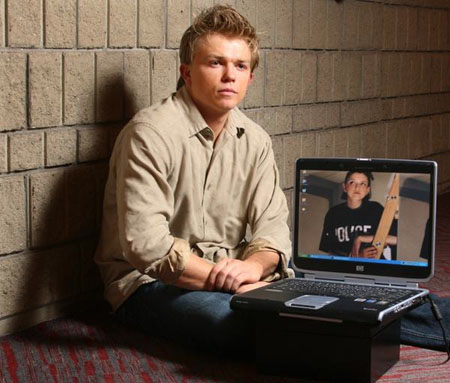

Craig Scott travels as a speaker with Rachel's Challenge to share the story of his

survival and his sister's life and death. (Photo courtesy Rachel's Challenge)

Monday was the 10th anniversary of the shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado. Staff reporter Tina Mather traveled to Columbine and spoke with the school's principal, the sheriff department's lead investigator and a student survivor and his family. Her interviews with the principal and investigator ran Monday and Tuesday. On Thursday Tina will have a behind-the-scenes look at "April Showers," the movie based on the shooting that opens this Friday.

Ten years ago, Darrell Scott never thought his daughter's death would become his life's work.

As he sits in his office in Littleton, Colo., just a few miles from where his daughter Rachel was murdered, he picks up a stack of papers from his desk.

"This is an email that came February 12, 2009," he says as he begins to read aloud. "'Rachel's impact on me was that I decided not to pull my trigger. The day you came to my school, I was planning on committing suicide.'"

He reads another: "'Well, the day we had the assembly I was going to hang myself because I was sick of life; no one seemed to care about me. I was cutting myself; having nightmares ... I decided that I would take a few days to think about it. And now I realize that I want to live.'"

He gets volumes of e-mails every month, but this particular collection -- over 100 since the start of the school year -- gets its own designation: Lives that may have been lost if his daughter's story had not been told.

A decade has passed since the Scott family lost 17-year-old Rachel in the Columbine attacks, but her legacy has remained alive in the story the family shares through Rachel's Challenge, an outreach program dedicated to motivating schools and communities to change their culture with a "chain reaction" of kindness and compassion. The non-profit program, based on writings Rachel left behind and the stories of the lives she touched, is now the largest school assembly program in the United States and reaches over 1 million students each year.

A Family Grieves

After the tragedy, the Scott family became emblematic of how the tragedy touched Columbine families.

Craig, who was 16 in 1999, came as close to death as one can get without actually perishing. He was in the library hiding under a desk when two friends, one on each side of him, were shot. After staring down two shotgun barrels and witnessing his friends' murders, he played dead.

"I was feeling overwhelmed and felt like my heart would stop beating," he said.

"I asked God to take away that fear. Then I heard God telling me to get up."

He was the first person to yell to the surviving students to get out of the room once the two student gunmen left.

When the shooters returned to the library a few minutes later, they would find no other students to kill before turning their guns on themselves.

A few hours after the shootings were over, Craig would find out that his sister was dead. Rachel was the first person murdered at Columbine, shot four times while she was eating lunch outside with a friend.

The Scott family was left with the loss of a daughter and a son who would lose two of his teen years to anger, nightmares and trauma.

Each member of the Scott family responded to the tragedy in a different way.

"I hated the two killers and used to fantasize about getting revenge. I was holding onto that anger and hatred and it was affecting my family and friends," Craig said.

Older sister Dana, now 32, struggled with how Rachel died.

"It wasn't that she was gone, necessarily, as much as it was, why in this violent way? Why was she shot four times?" Dana said. "Those were images and things that I had to not internalize but really deal with on the outside."

Rachel's father Darrell said he decided early on not to let bitterness grab hold of him. But he was still gripped with grief.

"It was like the life had been sucked out of me," Darrell said. "It wasn't so much anger that I struggled with as it was a deep, deep, almost -- I wouldn't call it despair -- but just a deep, deep sense of sadness."

Rachel's Legacy

Several months after the shooting, the family received Rachel's backpack from the Sheriff's Department. One of her journals was inside, the cover torn where a bullet had entered through her body and lodged in her backpack.

Inside, they found a rose she had drawn on the day of the shootings. The 13 clear tears falling from her eyes in the drawing turned into what looked like drops of blood as they surrounded the rose. There were 13 victims that day.

The Scott family started looking at all of her writings. Letters to friends. Essays. Journals. As the family found them, they began to put together a more complete picture of the purpose and spirituality that guided Rachel's life, and her growing premonitions that she would not live to see adulthood.

On May 2, 1998, she wrote, "This will be my last year Lord. I have taken all I can. Thank you." In another entry, she wrote a poem, saying, "All I want it is for someone to walk with me / Through these halls of a tragedy."

On April 20, 1998, a year before her death, she wrote to a friend, "Dear Sam, It's like I have a heavy heart and this burden upon my back but I don't know what it is. There is something in me that makes me want to cry."

She talked about wanting to reach young people.

Learning more about the purpose Rachel felt in her own life helped her family see through the horror of the tragedy. Her writings became instrumental in the family's healing process.

A few weeks after Rachel was killed, Darrell found an essay she wrote for her fifth period English class a month before the shootings. It was called, "My Ethics, My Codes of Life," and in it, Rachel wrote about kindness and compassion. She wrote, "I have this theory that if one person will go out of their way to show kindness and compassion, then it will start a chain reaction of the same."

In the essay, she used several words to define compassion; the first word she used was forgiveness.

"One of my mentors saw how it was affecting me and told me that forgiveness is setting a prisoner free and finding out that prisoner was you," Craig said. "I realized the anger and hatred was holding me back. What they did was evil and wrong, and if I had a gun I would have stopped them that day. But if I saw them now, I would want to reach out to them and have compassion on them."

His father agrees.

"Forgiveness released us to be able to celebrate Rachel's life instead of harboring anger and resentment and those things that do destroy a person," he said.

Rachel's Challenge

Rachel's essay formed the basis for the way the family shares the story of Rachel's life; it embodied what Rachel believed and how she lived.

"I was a jock and on the wrestling team. At times I was embarrassed by her, because she reached out to people that were not cool or popular," Craig said. "After the shootings, none of that mattered."

"She was a real, genuine person with a witty sense of humor. She wasn't perfect; she's not on a pedestal. But she did have character and went out of her way to reach people," said Craig.

They began to share her story. And the more they shared it, the more other people wanted to hear it.

Shy, reserved Dana overcame her fear of public speaking to stand before thousands of teens and talk about what happened. "I just kinda shocked my friends and family," she said. "I just knew I was supposed to share her story."

Today, the program talks about choosing positive influences, eliminating prejudice, goal-setting and living a life with respect and kindness.

"I think these are challenges [students] really want to see in their schools and in themselves," said Craig.

The Scotts started getting swamped with phone calls. They'd start to travel to schools, showing images of what happened that day, pictures of Rachel and her journal, and challenging teens to start a chain reaction of kindness and compassion.

"The whole concept sort of evolved from just the demand to have her story told," Darrell said. "We never hired a P.R. firm. We never intended to do this. It really came out of people hearing tidbits of her story and wanting to hear more."

"It just snowballed," said Dana. "And it's never slowed down, amazingly enough."

"We kind of live in this world where people feel powerless and that their voice or their actions don't make a difference because it's small or insignificant," Dana said. "And I think what Rachel's story does for those young people especially is, it says ... here's something you can do, and look at the huge difference it makes. It's so simple. It's small. But the impact has huge potential. And so I think that gives them a sense of empowerment and a sense of purpose just like Rachel felt."

Finding Purpose

Every time Craig speaks at a school assembly, he kneels down behind the curtain before it starts. And in much the same way as he did in the library 10 years ago, he asks for help.

"My faith has helped carry me," he said. "It's a healing thing to talk to God. At times it's hard to relive and share the story -- I have to turn to something bigger than myself."

In addition to speaking for Rachel's Challenge, Craig is pursuing a career in film. It's a choice that was confirmed for him when he learned how much the killers were influenced by violent media.

"In one of my classes at film school, we had to watch a movie that the two shooters watched over 100 times. The actors in it reminded me of exactly how they acted in the library," he said.

Craig has a passion for making films with a positive message. In addition to speaking for Rachel's Challenge, he's worked on a number of movies produced by Walden Media.

"I have a deep passion for making a difference that way," he said.

The 10th anniversary will likely be the last major media push of the Columbine story. But regardless of the media's involvement, their story has proven to transcend the newsworthiness of the 1999 attacks. The program is growing; the non-profit company founded by the Scotts now has a staff of 50 and is developing a corporate program. Thirty speakers, including Darrell and Craig, travel to schools and give one-hour assemblies, which are coupled with an evening presentation to parents and the community. In March Rachel's Challenge spoke to 150,000 students; this year they expect to reach 1.5 million total students with the program.

Dana, who now works full-time at the Rachel's Challenge offices helping schools set up and develop clubs in response to the challenge, knows the story of Rachel is a part of her life that she'll always have with her.

"Even if Rachel's Challenge ended tomorrow for some reason, I would still share Rachel's story wherever I went to work, if it was McDonald's or Dillard's. It's such a big part of me now, all I have to do is say the word Columbine and I've got the attention of a group of strangers in any room ... I've had people in tears sitting next to me and people on bus rides crying," she said. "I always have a story I can tell, that I can encourage people in. That's all I want to do with Rachel's story is encourage people."

Darrell will turn 60 this year. He says the travel is starting to wear on him, but he'll never grow tired of talking about Rachel.

Back in the Rachel's Challenge offices, he reflects on the purpose they've found through her life and death.

"Eight times the number of people are represented by these sheets of paper than died at Columbine," he said as he held the e-mails from this year of students who had decided against ending their lives after hearing Rachel's Challenge. "Their stories will never make the papers because it wasn't a sensational tragedy. But nevertheless, we know that hundreds of lives have been changed by her story."

After Rachel's death, it took a while for anyone to want to go into her room. For a long time, the family kept the door shut. But when they did go in, they found that Rachel had traced her hands on the top of her dresser. Inside the outline, she wrote, "These hands belong to Rachel Joy Scott and will someday touch millions of people's hearts."

And every year, for 10 years and counting, that is exactly what has happened.